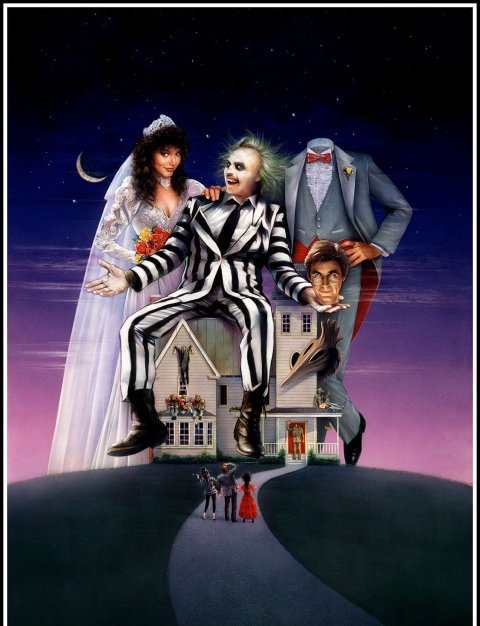

In Director Tim Burton's 1988 cult comedy Beetlejuice, the titular ghost, played by Michael Keaton, is on screen for a quarter of an hour, max. The film, an irresistible mix of anarchy and cartoonishness, focuses on the recently deceased Adam and Barbara Maitland (Alec Baldwin and Geena Davis), a painfully nice couple now haunting their beloved Connecticut fixer-upper. When pretentious New York yuppies buy the place and give it a vulgar postmodern makeover, their alienated Goth daughter, Lydia (Winona Ryder), enlists the creepy Beetlejuice to aid the Maitlands in scaring her parents out of the house.

Keaton made the most of his 15 minutes: Stardom followed that indelible and deliciously lecherous performance, which is why "those who grew up loving the movie forget it's essentially about a dead, childless couple and their search for a surrogate child," says Scott Brown, part of the team tasked with creating the $21 million Beetlejuice musical that's about to open on Broadway. "Beetlejuice's choices aren't what drive the movie—he's barely a character. He's more of a weapon that's unleashed."

Not enough, in other words, to wrap a two-hour-plus musical around. Instead, Brown; his writing partner, Anthony King; and the show's ringmaster, director Alex Timbers, shift the focus from the Maitlands to the relationship between Lydia and Beetlejuice. A Saturday morning cartoon, loosely based on the movie, had successfully made that move in 1989 (the show aired through 1991). "It was for kids, but it was smart, with a hipster credibility—there are a ton of memes around it online," says Brown. "Beetlejuice is less of an antagonistic source—more like Lydia's dead genie guy who makes funny cracks and does magic."

Timbers wanted to take it a step further, introducing a dynamic that's traditional in musicals. "Lydia and Beetlejuice are both essentially con men—like Max Bialystock and Leo Bloom (The Producers) or Harold Hill (The Music Man)—and to watch those kinds of characters outmaneuver each other is so much fun," says Timbers. "To put it really simply, Lydia is a girl who wishes she was dead, and Beetlejuice is a demon who wishes he was alive, and [the show] puts them on a collision course."

Beetlejuice was tantalizing for another reason. "He can break the fourth wall," says Timbers, "commenting on the action, being the MC and a narrator—as well as an unreliable narrator. He brings an anything-can-happen danger to the proceedings, both to the characters onstage and to the audience."

Timbers' résumé includes the Broadway shows Bloody, Bloody Andrew Jackson, Peter and the Starcatcher and The Pee-Wee Herman Show—clever, antic productions crammed with visual invention, snappy dialogue and a Burton-style do-it-yourself sensibility. (Coincidentally, Pee-Wee's Big Adventure was Burton's first film, followed by Beetlejuice.) It was Timbers who asked Brown and King to write the book. That was 10 years ago, though the show—a property of Warner Bros.—didn't really get going until 2013, when Australian composer Eddie Perfect (King Kong) was hired to do the score.

"One of the big questions Anthony and I had as we were writing the book was 'How does Beetlejuice sing?'—particularly with his level of irony," says Brown. "And Eddie came out of the gate with a song that is now the opening number, "The Whole Being Dead Thing," a full-frontal assault, switching between different tempos and styles, and Beetlejuice unleashing his genie-like energy and owning the stage." Also, he adds, "it just really made us laugh. Eddie's a genius at writing artfully uncouth songs."

Brown and King—who first worked with Timbers on their Upright Citizens Brigade comedy Gutenberg! The Musical! in 2006—are multi-hyphenates: performers and creators who come at musicals from multiple angles (both write for TV, King ran UCB in New York for five years, and Brown just published a young adult novel). "What Scott and Anthony bring is a real love and respect for musical theater as well as for downtown theater and cutting-edge comedy," says Timbers. "And Eddy, he's a musical director, a cabaret performer, the star of a big TV show in Australia, he can write book and score. He even performed in South Pacific."

Beetlejuice introduced Burton's gothic-fantasy aesthetic, as well as eye-popping (literally, at times) effects, and Timbers and his scenic designer, David Korins (Hamilton), had to wrestle with the question of whether to "run towards that unique visual world or away from it. We decided to run towards it," says Timbers. But rather than simply replicate the movie, "which would have been predictable, we dug into Burton's work in total, right back to his college sketchbooks. Paying homage to his entire oeuvre—that was interesting to us." (Burton, by the way, has no involvement in the show and has yet to see it.)

The musical's palette, like Beetlejuice's prison-striped suit, is largely black and white with judicious pops of vivid color. William Ivey Long (The Producers, Hairspray), who created the costumes, had an interesting challenge: How do you do a black-and-white character on a black-and-white set? "He was looking at the properties of stripes—what's a straight stripe, what's a windy stripe, what's a stripe where it's 60 percent black and 40 percent white," says Timbers. "We looked at optical art. We looked at all this stuff that was adjacent to Burton, like Edward Gorey."

The director and designers were also intent on preserving the tactile, homemade quality of the film, like the stop-action sandworm. What was the analogue of that on Broadway? Puppets, for one thing, says Timbers, "because they don't look and feel expensive." Or touches like "hand drawing the wallpaper in the first home in the show." The director's 2012 production of Rocky: The Musical had been challenged by formidable mechanics. There's no dearth of ambition in Beetlejuice, but here Timbers and his team "wanted a much more charming, lo-fi quality."

The show's stars were found, including Alex Brightman (School of Rock) in the titular role and Sophia Anne Caruso as Lydia (already an industry vet at 17 and "a true prodigy," says Brown). So far so good.

And then came last October's out-of-town tryout at the National Theater in Washington, D.C. Audiences seemed to love the show—the creators were cautiously optimistic—until the critics barbecued it ("overstuffed and crude" was Variety's take). Most found the character of Beetlejuice alienating and abrasive. "D.C. did exactly what we hoped it would," says Timbers. "It's a very smart theatergoing town, and we got lots of great feedback."

"What we learned was that Beetlejuice was blowing people's hair back in every scene," says Brown. "We had wanted to keep things fast and funny, ahead of whatever the audience might be catching up with, but we had stepped on the gas so hard we were leaving the audience behind. It's never fun to get backhanded," he adds. "We had a very eventful six months after that."

The focus immediately became building what Timbers calls "emotional on-ramps" for the characters, as early as possible. "You're always trying to do that in musicals, to open the tent flaps and let more people inside."

While the structure of the show remains the same, jokes and ad-libs have been "significantly de-raunched while retaining a comedy club edge," says Brown, and the character of Beetlejuice has been deepened and enhanced, particularly "the underlying reasons for why he does what he does, why the Maitlands and Lydia are important to him and why she's so death-obsessed." Brown and King had always intended to have a little pathos in Beetlejuice, it had just gotten lost in the jokes. "He's a ridiculous figure, but there's an underlying loneliness, which is a big theme of the show. Life is other people and community; death is the oblivion of being alone."

Brown, among his many other hats, briefly wore that of a theater critic for New York magazine between 2013 and 2014 (disclosure: I hired him for that position). "That definitely changed how I write for theater," he says. "It reminds you to think about how things are received on the other end."

At Beetlejuice's first Broadway preview, on March 28, the line for that night's sold-out show wrapped around the block of the massive Winter Garden Theatre, former home of Cats and, yes, Rocky. (In the crowd was Irving Burgie, the 94-year-old creator of the song "Day-O," which is a movie highlight and the musical's first act closer.) Inside, the audience was exuberant: The jokes were landing, the emotion was registering. Behind the scenes, the tweaking continued, with King and Brown sweating every detail before the April 25 opening and the show-making-or-breaking reviews of New York's theater critics. "It's so exciting to see Scott's and Anthony's wonderment of, 'Oh my God, it's my Broadway debut,' says Timbers. "How fun is that—how awful is that?"