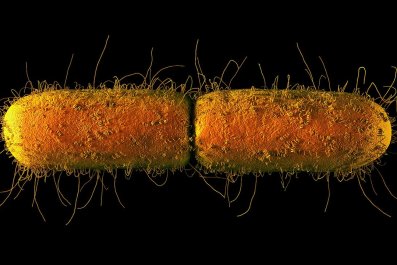

Medical researchers have known for decades that the pipeline for new drugs to stave off bacterial infections would one day run dry. That day is now at hand.

In some cases, doctors have no drugs to give their patients for what once were treatable infections but are now life-threatening. Although researchers have many good leads, the bigger problem is a lack of financial incentives to bring new treatments through the drug-development gantlet.

"When I signed up to be an infectious disease specialist 25 years ago, I never thought it would come to this," says Helen Boucher, a physician at Tufts Medical Center in Boston and director of its infectious disease fellowship and heart transplant programs. Boucher has been a leading advocate for finding ways of investing in new treatments. She spoke with Newsweek about the drug-resistance problem and how we might dig our way out of it.

In terms of the scope of the drug-resistance problem, do you believe we are approaching a crisis?

The crisis has already arrived. We are in an era now when doctors like me have no effective antibiotics for some of their patients.

Is there anything in the wings that gives you hope a potential solution is on the way?

There is a lot of research going on that could give us good solutions. The pipeline isn't quite as empty as it was 10 years ago. Phages [bacteria-killing viruses], vaccines against infections, new diagnostic methods and monoclonal antibodies [immune-system boosters] are all innovative and promising lines of research.

Some of the technical and scientific hurdles are high, especially with vaccines. But we could target a vaccine at people we know face a specific kind of infection risk, such as people who are getting open-heart surgery, a common operation with a high risk of infection. We'd vaccinate you a week or two before surgery. Even if we only had vaccines for one or two types of infections, it would save thousands of lives.

But is the research moving quickly enough?

The research isn't the problem. We are seeing innovative research in the pre-human-trial phase from small biotech companies that are fully ready to pursue human trials. But nobody's lining up to pay for it. Sales wouldn't bring in enough to justify the cost. We're seeing existing antibiotics manufacturers at or near bankruptcy, and small biotech companies are struggling. We can foster innovation, but if there's no market waiting to nurture the results, it will just be a wasteland. We need something fast, but it's a hard sell in this environment.

How can we get past this bottleneck and lack of funding?

We need a better way to value new antibiotics and treatments. The expectation now is that they should be cheap and widely available. We pay many thousands of dollars for cancer drugs that may prolong life only for months or even weeks, but antibiotics can cure someone who's critically ill and give them their full life back. There's a real value disconnect.

Many of us are working on "pull incentives" for antibiotic drug developers, which involves finding ways to reassure them that they'd get some return on their investment when the drug gets to market. That might involve "delinkage," which means that remuneration wouldn't entirely depend on sales. There would be other mechanisms for making money. Separating sales from profits would also help avoid incentivizing antibiotic overuse.

One short-term solution would be for Medicare to reimburse hospitals for the high cost of new antibiotics separately from the flat fee Medicare pays for treating someone with a given medical condition. Right now, hospitals are incentivized to use cheap drugs that may be less effective, because the cost comes out of the flat fee. A longer-term solution would be offering "market-entry rewards." If a company develops a drug that treats resistant infection, it would be promised a return of $500 million to $1 billion.

We're still debating how to pay for some of this. One idea is to do what we do now with vaccines—where every time a vaccine is given, a small amount of money goes to a fund to cover some of industry's costs. We could do that for antibiotics and use the fund to provide market-entry rewards.

Shouldn't the government be covering the cost of some of this?

The government has been investing in antibiotic drug development for some time. We're three years into the five-year CARB-X effort, a public-private international partnership that's investing more than $500 million in the industry for early drug discovery and development. There's also been money from the GAIN [Generating Antibiotic Incentives Now] act and the 21st Century Cures Act.

All this helps, but it's going to be a 10- to 15-year process to reinvigorate the pipeline. Where we are right now is scary.