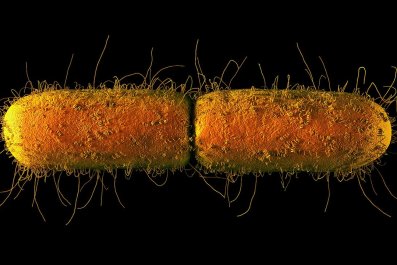

For Borrelia burgdorferi, the bacterium that causes Lyme disease, these are the good old days. Because of a proliferation of white-tailed deer and other mammals that harbor the microbe and a seemingly endless supply of ticks to transfer it from deer to human bloodstreams, an estimated 300,000 people are infected each year in the United States. Left untreated, Lyme disease does a lot of damage: It can attack the heart and nervous system and trigger arthritis.

Fortunately, B. burgdorferi has not yet developed a resistance to antibiotics. That's good news for most bite victims who are lucky enough to notice the early symptoms—fever, headache, chills, fatigue, joint and muscle aches and swollen lymph nodes, plus a rash up to 12 inches from the bite site—and seek treatment with a three- to four-week course of antibiotics.

But not all patients walk away scot-free. For reasons that are obscure, one in 10 patients treated for Lyme disease continue to have symptoms for months and even years. These patients fall into a gray area called post-treatment Lyme disease (PTLD) syndrome, which is characterized by cognitive dysfunction, incapacitating fatigue and chronic pain, according to a study published in April in the journal BMC Public Health. The cost to the medical system is estimated at up to $1 billion a year in the U.S.

Doctors have sparred over what might cause PTLD syndrome. Some thought a few renegade cells of B. burgdorferi, which is notoriously clever about evading the body's immune system, somehow survived the antibiotic treatment, settling in for the long haul and causing "chronic Lyme disease." Recent research has cast doubt on that view, but researchers still have no good working hypothesis.

Whatever the cause, the number of people who have PTLD syndrome seems to be on the rise. In the BMC Public Health study, scientists estimated how many people currently have PTLD and how fast the number of cases may be increasing. They drew on data collected by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, as well as past estimates of Lyme disease rates, survival rates and examples of treatments failing.

The two estimates varied widely. When they assumed a treatment failure rate of 10 percent, new cases rose steadily between 1980 and 2005 before slowing by 2020; the number of PTLD cases rose from about 69,000 in 2016 to more than 80,000 in 2020. When they assumed a treatment failure rate of 20 percent, they found that the number of cases would reach 1.9 million by 2020.

"Nevertheless, our findings suggest that there are large numbers of patients living with LD-related chronic illness," the scientists wrote. Further research is now needed to create tests to accurately diagnose and treat the condition, raise public awareness and arrive at a conclusive figure on the number of sufferers.