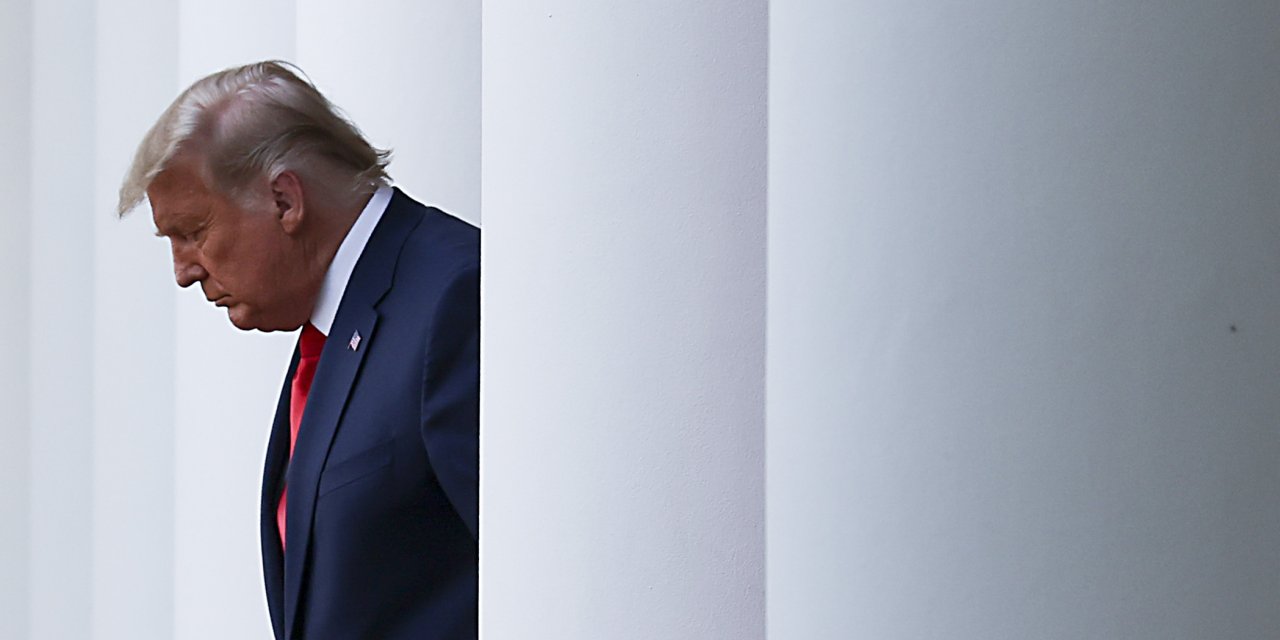

With the Trump campaign scoring just one victory so far out of the more than 30 lawsuits it has filed in six states, it wasn't exactly a surprise when a Philadelphia appeals court last week became the latest to reject a challenge by the president to the results of the election. What was noteworthy was the scathing nature of the decision written by a Trump-appointed judge, who dismissed the case as having "no merit." Also significant but largely unnoticed as electoral drama consumed the nation: The string of legal losses and dismissals suffered by the campaign is just one of several major defeats the courts have handed Donald Trump this fall on a wide variety of issues—and that, despite the large number of judges the president has appointed while in office, such defeats have been a common occurrence for his administration.

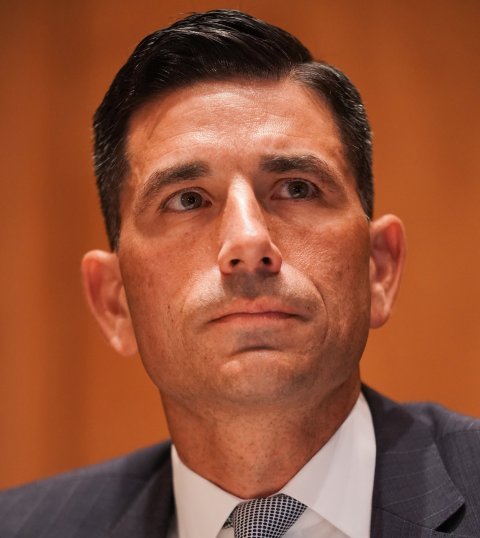

Just this week, for instance, a California federal judge struck down the administration's policy tightening eligibility and raising minimum salaries for foreign employees who come to the U.S. on high-skilled work visas. Federal judges this fall also ruled that two Trump appointees—Chad Wolf as acting Homeland Security secretary and William Perry Pendley as administrator of the Bureau of Land Management—were illegally installed, which means that much of their work in those roles must be voided. Another setback this October: TikTok, the video-sharing site, successfully sued to block an order from the Commerce Department to force app stores to stop offering the service. And that same month, Trump's attempts to have the Justice Department step in to represent him in a defamation lawsuit brought by a writer who accused him of sexual assault were obliterated by a federal judge in New York.

What's more, the rulings, in both the election-related suits and the non-election matters, have come from judges across the political spectrum—conservatives and liberals, Democrats and Republicans, some of whom were appointed by Trump himself.

Indeed, in an era when Congress has rarely pushed back against expansions of presidential authority and when no amount of media scrutiny has cowed the president's persistent efforts to demolish norms, one bedrock institution has stood alone in saying no—and saying it repeatedly—to Donald Trump: the courts.

"Despite his attempts to flout the rule of law, when [Trump has] acted egregiously outside the scope of his authority, the courts have really knocked him down," says attorney Marisa Maleck, a former law clerk to Justice Clarence Thomas who served as general counsel to the District of Columbia's Republican Party before resigning in 2016 after Trump won the presidency.

Maleck, in fact, was one of dozens of conservative legal scholars who signed a letter before the 2016 election warning that Trump was unfit to be president because they did not "trust him to respect constitutional limits in the rest of his conduct in office." As it turned out, they were right to be nervous about Trump's interest in exceeding his boundaries or reshaping the judiciary. As of December 2, Trump has had 229 judicial appointments confirmed, for an average of 57 judges for each year he's been in office. That far outpaces his two predecessors, George W. Bush and Barack Obama, both with about 41 confirmed judges per year. (Only another one-termer, Jimmy Carter, had a higher average than Trump, with more than 65 per year.)

On a surprising number of instances, even the increasingly conservative U.S. Supreme Court flummoxed the president. When Trump attempted by fiat to rescind the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program, which allowed undocumented immigrants brought to the U.S. as children to stay, the Supreme Court rejected the idea by a 5-4 margin. When Trump wanted to add a question about citizenship to the 2020 Census, the Court again rejected the idea by a 5-4 margin because his agencies failed to "offer genuine justifications for important decisions, reasons that can be scrutinized by courts and the interested public," as Chief Justice John Roberts wrote last year.

Even his own appointee, Justice Neil Gorsuch, who joined the Court in 2017, hasn't always toed the line. Gorsuch wrote the majority opinion against the Trump administration in a 6-3 ruling last June that found LGBTQ employees are protected from employment discrimination under the 1964 Civil Rights Act. A month later, both Gorsuch and Trump's second appointee, Justice Brett Kavanaugh, joined a 7-2 ruling against Trump in which he tried to block the release of his taxes and other financial records to a grand jury in a criminal proceeding just because he's the sitting president.

"In our system of government, as this court has often stated, no one is above the law," Kavanaugh wrote. "That principle applies, of course, to a president."

"The Supreme Court decisions regarding Trump's taxes this past term was a surprise," says Chicago attorney Pejman Yousefzadeh, another co-signer of the 2016 letter. "With the efforts made to create a conservative court, I was concerned that the court would be excessively deferential to him. It was refreshing to see that that didn't happen."

This check on Trump is what conservative legal theorists who supported him were counting on, New York University Law Professor Richard Epstein says. "We would never vote for him if we really thought, for example, that he was going to seize power and prevent the transition" to a successor, Epstein says. "I think the system is basically held on this issue. And I think it's a compliment to the system because he does have really autocratic tendencies. I don't think there's anybody who doubts that."

No Partisan Divide

At no time have the courts so uniformly and dismissively stymied Trump than over the past two months as judges from across the political spectrum and the nation shot down dozens of cases brought by the president or Republican allies seeking to make voting more difficult or overturn President-elect Joe Biden's victory.

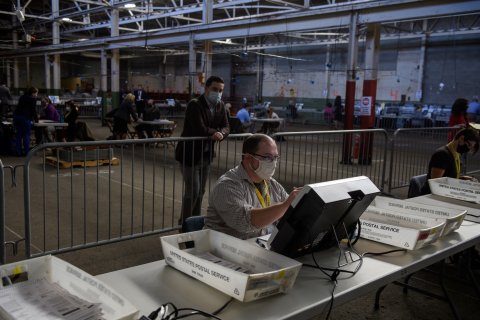

The day before the November 3 election, for instance, anti-Trump forces held their breath as U.S. District Judge Andrew Hanen, an appointee of President George W. Bush known for strident conservative leanings, weighed whether to throw out nearly 127,000 early votes cast in Houston at drive-through polling places. Hanen ultimately ruled the votes would count, the same decision made the day before by the all-Republican-appointed Texas Supreme Court.

Weeks later, it was a flurry of five losses in a single day at the Democratic-majority Pennsylvania Supreme Court, in cases striving to throw out thousands of ballots, that seemed to precipitate the president's decision to give the General Services Administration the go-ahead to formally begin a Biden transition. The decisions, handed down on November 23, came two days after Federal District Judge Matthew Brann, a well-known Republican appointed by Obama to the federal bench in 2012, dismissed a Trump campaign lawsuit that sought to invalidate millions of Pennsylvania votes.

In a blistering decision, Brann, who was recommended for the bench by GOP Senator Pat Toomey of Pennsylvania, said the Trump team's claim of widespread improprieties with mail-in ballots were based on "strained legal arguments without merit and speculative accusations" and were "unsupported by evidence." Four days later, when the latest Pennsylvania case made it before the Federal Appellate Court, it was Trump appointee Stephanos Bibas who sharply repudiated the president's efforts to overturn the 2020 election, writing: "Charges require specific allegations and then proof. We have neither here."

"A Mixed Record," Overall

Yet while almost all the recent election-related decisions have gone against Trump, some legal experts point out that the courts did give Trump several important pre-election victories on the voting process and some key wins on other topics as well.

The Supreme Court, for instance, reversed lower court rulings that extended the time for acceptable arrival of absentee ballots in Wisconsin and to make absentee balloting easier in Alabama and Texas. The high court, in earlier cases during his term, also allowed Trump to redirect federal funds to build the border wall even after Congress refused to allocate the money; to delay providing his tax records to House committees investigating him; and to ban immigration from a select group of Muslim-majority nations, says Erwin Chemerinsky, dean of the University of California at Berkeley School of Law.

"Yes, the courts have done more to check President Trump than Congress has, but it's a mixed record," Chemerinsky says. "My biggest fear was the courts would issue an order to the Trump administration and Trump would say, 'I don't care what the courts say, I'm going to do it or not do it anyway.' Then the rule of law is over."

The constitutional crisis that Chemerinsky and other legal experts feared never materialized. Yet the Berkeley dean remains alarmed by the failure of the courts to move more quickly on pending legal action that accuses Trump of violating the Constitution's emoluments clause, which bars a president from personally profiting from his position—including one lawsuit that Chemerinsky is part of. As part of the legal team representing the Citizens for Responsibility and Ethics, he sued Trump three days after he was inaugurated in 2017. Nearly four years later, after a big CREW win at the appellate level, the case is pending before the Supreme Court.

"This isn't going to be ruled on during the four years of the Trump presidency," Chemerinsky says. "There have been two other emoluments clause suits that spent the entire four years at the procedural level. It's astounding. The claim was that the president every day is violating the Constitution and yet the court has spent the entire time just on whether or not the plaintiff has standing to be able to sue. There is a place where the courts have not checked the president."

Yousefzadeh says Trump's team used the court's slow pace, too, to create roadblocks for Congress in trying to compel testimony in a panoply of corruption probes including those related to foreign meddling in the 2016 election and Trump's efforts to persuade Ukraine to launch a criminal probe of Biden's possible involvement of the ouster of the country's prosecutor general. Dozens of subpoenas were defied with claims that the likes of former Chief of Staff Don McGahn or National Security Adviser John Bolton's discussions with Trump were protected by executive privilege. Representative Adam Schiff, chair of the House Select Committee on Intelligence and a leader in efforts to investigate the president, said he moved ahead without hearing from those witnesses to present the two articles of impeachment that passed against Trump because litigating those subpoenas would take too long. "We are not going to allow the White House to engage us in a lengthy game of rope-a-dope in the courts," Schiff said in October 2019.

"One of the legacies that really concerned me from this is if the courts won't enforce subpoenas to testify before Congress, and if Congress won't enforce them even through impeachment proceedings, why would anybody comply?" Chemerinsky asks. "The subpoenas are meaningless now."

An Independent Streak

Still, Maleck says, Trump lost more in court than she expected, a fact that she believes also surprised a president who, during his 2016 campaign, told an evangelical Christian audience: "If it's my judges, you know how they're gonna decide." He repeated similar remarks so often during his tenure, dismissing many judgements that went against him from Obama appointees as politically motivated, that Chief Justice Roberts rebuked him. "We do not have Obama judges or Trump judges, Bush judges or Clinton judges," Roberts told the Associated Press in 2018. "What we have is an extraordinary group of dedicated judges doing their level best to do equal right to those appearing before them."

In the flurry of election-related cases, Bibas wasn't the only Trump-appointed judge to shoot him down. On November 19, U.S. District Judge Steven Grimberg dismissed a lawsuit brought in Georgia that sought to have the presidential election results thrown out due to changes in how voters' signatures were verified. "To interfere with the result of an election that has already concluded would be unprecedented and harm the public in countless ways," wrote Grimberg, appointed by the president last year.

Says Maleck, "That highlights how strong the separation of powers really are."

Epstein is not surprised. The selection of judges had been outsourced to Federalist Society vice president Leonard Leo, a longtime conservative legal activist who provided the administration with lists of preferred judges, Epstein says. Those who made the cut had "an intellectual integrity and a real commitment to judicial restraint, property values and separation of powers. The thought that these people would do his political bidding—you're dreaming. Not going to happen."

Another front on which Trump was flummoxed: None of his political foes or foils—Obama, vanquished Democratic opponent Hillary Clinton or Biden's son Hunter—were prosecuted by his Department of Justice. This, too, is seen as a credit to the strength of the judiciary inasmuch as the court system wouldn't tolerate it, Yousefzadeh says. "What prevented the 'lock him up' or 'lock her up' chants from becoming realized is the fact that you did actually have good people in the Justice Department who said, 'This is ridiculous, this is a non-starter' and even the current attorney general realized that this would be an appalling step too far," he says.

Ironically, Trump's conservative appointees may end up curbing executive power down the line. In recent decades, as Congress has been gridlocked, presidents have increasingly tried to use executive orders and rules promulgated by agencies to make policy. University of Nebraska Law Professor Gus Hurwitz, another co-signer of the 2016 letter expressing fears about Trump, believes the federal judiciary molded by Trump— which is dominated by originalist judges who believe in interpreting the Constitution as it was understood when first written and who particularly revere the concept of separation of powers—"is probably going to be at the vanguard of reversing that trend and saying to future administrations, 'No, you need to go back to Congress and ask them to clarify or update or change this law' and 'Congress, you need to clarify or update or change this law.' So I'm optimistic for the viability of our constitutional order and the role of the separation of powers and the separate branches of government fulfilling each of their purposes."

For his part, Epstein finds all of the fear about Trump to have been overblown. "Ask yourself the following simple question: Has Donald Trump ever disobeyed a court order?" Epstein says. "The answer is no. No one's going to deny that he has certain kinds of autocratic tendencies or that he has a certain kind of intellectual instability. He's won some, he's lost some, but his bark is much worse than his bite as far as I can tell."

Yousefzadeh remains anxious, though, that the judiciary has sustained damage under Trump, who showed future would-be autocrats the loopholes and weaknesses to exploit even if Trump himself wasn't clever enough to take full advantage.

"I would like to think the courts would remain the last line of defense, even if the justice department were fully bent to a future president's will," Yousefzadeh says. "But we've seen how many norms have gone by the wayside over the past four years, and that was with a relatively incompetent president. I shudder to think of how much worse it could be if a president who had it together far more on a personal level might come along and renew and assault on our legal institutions."

Steve Friess is a Newsweek contributor based in Ann Arbor, Michigan. Follow him on Twitter at @SteveFriess.