In a new book, The Age of AI, the somewhat unlikely pairing of statesman Henry Kissinger, tech CEO Eric Schmidt and academic Daniel Huttenlocher joined forces to analyze the capabilities, limitations and safeguards required for artificial intelligence (AI). In the Q&A below, the three authors discuss their partnership, the likelihood—or not—of an AI takeover, the most promising uses of AI and more.

Newsweek: You're a dream team. How did you find each other and decide to work on this topic?

Eric Schmidt: Writing this book together has been a pleasure—and a welcome source of community during the pandemic. When Henry and I met a decade ago or so, the first thing he said to me was: "The only problem I have with Google is that I think that you're going to destroy the world." I thought, "Well, that's a challenge from Henry Kissinger!" After a few years, alongside Dan, our conversations became this book.

Henry Kissinger: We started having regular conversations after Eric introduced me to AI. We were at a conference. AI was on the agenda. I almost skipped the session, but he stopped me; he persuaded me to stay. That was five years ago.

Daniel Huttenlocher: During the pandemic, we met every Sunday for two, three, sometimes four hours and talked about AI. No one, by themselves, can understand what AI is, may become or what it will mean. But our different perspectives—a former secretary of state, a former CEO and an academic—helped us ask the kinds of questions we think more people should be asking.

When the layperson hears about AI, they often think about an AI takeover, or movies like Terminator or The Matrix. Is there any basis in reality for these concerns?

ES: No, there isn't. AI isn't novel because it's trying to take over the world (it isn't); it's novel because it's imprecise, dynamic, emergent and capable of learning all at the same time.

DH: Explaining AI is difficult even at MIT, where people have a high level of technical knowledge. What it can do is easy to see—diagnosis, translation, winning games—but when it will work and how it works are difficult to understand. It isn't a specific technology or industry, it's an enabler—and it enables scientific discovery, social media, video streaming and other human-level activities from conveniences to saving lives.

Do you think AI could create an identity crisis for humans?

HK: After the Enlightenment, in the Age of Reason, we ascribed to the centrality of our abilities to investigate, understand and explain the world we live in. Now, AI is undertaking the same processes differently than we do: it's studying games and devising new ways to win them; it's studying compounds and discovering new ways to combine them to treat illness. We humans need to define our role in this reality.

ES: AI is a different intelligence—it's not human, but it's human-like. It can be a companion to children or even the elderly. What, exactly, that will look like, we have to decide.

DH: The title of our book, The Age of AI: And Our Human Future, is purposeful. The rise of AI is inevitable, but its ultimate destination is not. It raises existential questions, but they need not be existential crises. We can—we should—develop, guide and shape AI, ensuring our future is human, not mechanistic.

In what ways do you think the global community needs to collaborate relating to AI? Must foreign governments share norms and come to agreements regarding its uses?

HK: AI will both complicate existing strategic dilemmas and create novel ones. Frankly, AI could be as consequential as the advent of nuclear weapons—but even less predictable.

ES: We need to discuss limits and red lines now. We don't yet have the diplomats, or even the vocabulary, but we need to start; they'll develop. The National Security Commission on Artificial Intelligence, which I chaired, recommended dozens of international partnerships, especially partnerships to guide AI in the direction of democracy.

DH: It's crucial that everyone—not just technologists, regulators and companies—think about what AI will enable. This will require cooperation and collaboration locally, nationally and globally across industries and domains, from academia to agriculture.

What do you see as the most promising use of AI in the very near term?

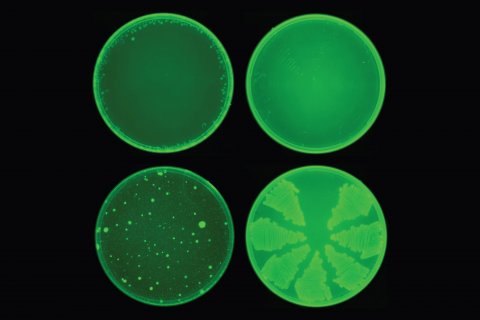

DH: AI is already transforming human life. Earlier, more accurate medical diagnoses for diseases like certain cancers are promising. So is language translation, which opens up broader horizons. AI is increasingly enabling new scientific discoveries that will have broad positive impacts on human health and welfare.

ES: Yes, we're excited about AI's improvement of—and potential to continue to improve—human health. I recently launched the Schmidt Center at the Broad Institute to merge biology and machine learning to fight disease like we've never fought it before. Additionally, I'm excited about AI's impact on learning, which I think will finally move us beyond the model of 30 students, one teacher and one chalkboard. If learning can be more personalized, more children can reach their potential.

What advances could it be used for farther in our future? How distant could these be?

ES: A lot of problems persist because either computers can't figure them out or computers don't have enough data to figure them out. AI can help us make progress on the really tough ones: mental health, drug addiction and abuse, inequality. It can build better climate models. And it will transform biology, chemistry and material science—the bases of the next trillion-dollar industries.

In order to program an AI for the most effective machine learning, experts in various fields must collaborate, I imagine—much as you three did to write this book. Will the products of AI make the skills of collaboration more or less of an imperative?

HK: More. But the collaboration will be new: it will be with machines. Of course, collaboration among nations, corporations and disciplines, both about what AI is and about how it should be limited, will be imperative too.

ES: We have three choices: we can resist AI, defer to AI or partner with AI. We should partner with it to shape it with our values.

DH: Expertise in machine learning, in the application domain, and in societal implications of the application are all important. These are increasingly all part of the teams deploying machine learning. But beyond this, increasingly we need to consider the broader philosophical and historical context of what AI means for human experience and values.