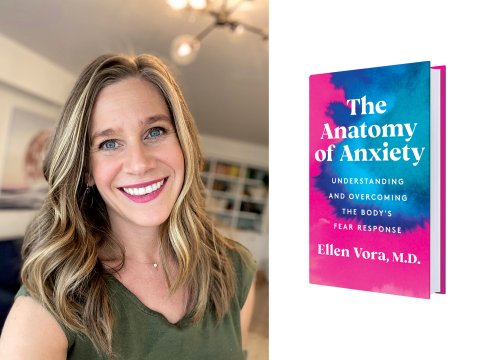

With symptoms of anxiety and mental health disorders growing threefold between 2019 and 2020 according to the CDC, new ways to address this "epidemic of anxiety" are needed. Functional medicine psychiatrist Ellen Vora, MD shares her holistic approach in her new book, The Anatomy of Anxiety (Harper Wave, March). In this Q&A, Vora discusses how she predicts the pandemic will affect mental health long-term; the most significant thing we can do to change our behaviors to minimize anxiety; her food recommendations to decrease inflammation and improve gut health; and more.

Why this book? Why now?

When I meet a patient with anxiety, on some level, I'm excited. There is so much low-hanging fruit—so much we can do to improve anxiety. We were already in an epidemic of anxiety before the pandemic, and it's fair to say the book is even more needed now that we've all been through two years of struggle and collective grief.

Do you see results faster when treating anxiety with your methods than with medication alone?

Absolutely. Medications can take a few weeks to work, and many of my patients are not sufficiently helped by meds. Identifying and addressing the source of physical anxiety can have someone experiencing relief within a matter of days.

What types of complaints have you been seeing from the last few years? Do you think these heightened levels of anxiety will remain as a vestige of the pandemic or will they resolve with the pandemic (whenever that may be)?

Our mental health responses to the pandemic are varied and ever-evolving. In the early days, I saw many people start out with acute anxiety, accompanied by worry, insomnia and, for some, panic attacks. As time passed, many people have burned through their "surge capacity," shifting their mood to a state of depletion and exhaustion, where they may be languishing or feeling a lack of motivation or hope. I think we'll see gradual improvement, but some impacts of the pandemic will unwind slowly—for example, many of us have developed a habit of heightened worry that can be difficult to unlearn.

What is the most significant thing we can do to change our behaviors to minimize anxiety in our lives?

Three-part answer: Get the phone out of the bedroom, eat real food and prioritize community and connection in our lives.

Do you find that patients feel dismissed by the term "false" anxiety? Or does it give them reassurance that their concerns are manageable?

Indeed, many people find the term invalidating, and I can understand why. Apologies! The term "false" was never intended to invalidate the very real suffering of anxiety. It instead speaks to the straightforward path out of this kind of avoidable and unnecessary anxiety.

What about "true" anxiety? How can you tell the difference? And how can you address it?

To discern the difference, it's helpful to begin by taking inventory of the various causes of false anxiety and address those first. Once you've eradicated much of your false anxiety, you can begin to recognize the true anxiety that exists underneath. There is also a different quality to this type of anxiety—if we really pause to listen to it, it centers around a cause that feels uniquely important to us. True anxiety is purposeful anxiety. My best suggestion for hearing the communication of our true anxiety is to carve out time to be still and quiet and truly listen to any communication that bubbles up from within.

What foods do you recommend either cutting out of the diet or adding to it to decrease inflammation and improve gut health—and ultimately reducing anxiety?

Everybody's different, and there is such a delicate art to this process—you want to nourish your body in a way that gives your brain what it needs to function well without driving yourself crazy or becoming obsessive or fearful of food. That said, many of my patients benefit from a trial elimination diet to detect if foods like gluten, dairy, sugar and industrially processed vegetable and seed oils impact how they feel. Meanwhile, we need to focus most of our energy on bringing in more of the foods that meet our nutritional needs—healthy fats, a diverse array of well-sourced proteins (eating a variety of different animals and every part of the animal), starchy tubers, fermented foods, bone broth, fresh fruits and plenty of deeply pigmented vegetables. When it comes to feeding ourselves, we also need to keep an eye toward pleasure, for this is also medicine.

You also discuss practices such as meditation and gratitude practices. How do they fit in?

Meditation is a great technique for tipping your nervous system out of a stress response and into a relaxation response. It's also a surefire way to open up lines of communication with your true anxiety.

What caused you the most anxiety during the pandemic? Are there practices to improve mental health that you've implemented in your own life recently?

For me it has actually been the hyperpolarization and rifts that have formed within families and friendships. I think we have a lot of repair work to do around expanding our capacity for compassion, empathy, understanding and bringing nuance back into our debates as we all try to navigate a dizzying information landscape. My go-to practice for maintaining mental health has been time in nature.

What podcasts or books are you listening to or reading now?

Pulling the Thread, a podcast with Elise Loehnen; and I've gone back to reading fiction. I'm currently reading a memoir called I Am, I Am, I Am by Maggie O'Farrell. After so many years reading every nonfiction book about optimizing health, I've realized that the best way for me to support my patients these days is to hold space for their psychospiritual well-being. It turns out, fiction gets at those complexities of the human condition far more effectively.