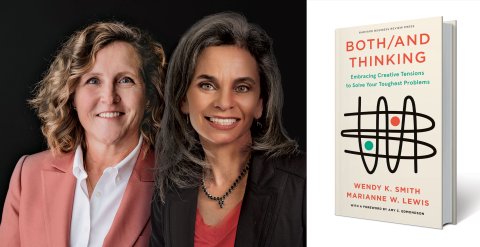

Relationships—whether personal or professional—take work. When there's conflict, changing your mindset and understanding the other person's perspective can go a long way toward resolving differences. In their new book, Both/And Thinking: Embracing Creative Tensions to Solve Your Toughest Problems (Harvard Business Review Press), paradox experts Wendy Smith and Marianne Lewis discuss how to use "both/and" rather than "either/or" thinking to help people get along. In this Q&A, Smith and Lewis address how this thinking can be put into practice in various ways, including when trying to balance profits and social responsibility in the workplace, for female professionals trying to "have it all" and for couples with opposing parenting styles.

What is both/and thinking? How does it compare to either/or thinking?

Smith: As parents, partners, employees and leaders, we're caught in tug-of-wars. Do we prioritize work or family, current targets or learning new skills, social or financial needs? Facing a dilemma, we typically make a choice: A or B. We then stick with that choice. This either/or thinking can be helpful in the short run. Yet it limits our options. Worse, it can lead us down a rabbit hole, overemphasizing one side until we're stuck.

Both/and thinking starts with recognizing paradoxes within our dilemmas. Think yin-yang. Interwoven contradictions reinforce each other. Light defines dark and vice versa. In life, beneath work/life dilemmas lie paradoxes of self/other, short-term/long-term, giving/taking. Caring for ourselves creates energy and resources to care for others. Caring for others generates goodwill and support for ourselves. Noticing paradoxes helps us embrace tensions and find more creative, lasting solutions.

More and more, people today exist in "echo chambers" where the only opinions they hear—or want to hear—are those similar to their own. Why should we want to broaden our perspectives?

Lewis: We're not sharing much these days. We're in trench warfare. Each side thinks it has the answer. They dig in, surrounded by like-minded others, dehumanize the opposition and fire away. The nastier the insults, the deeper the trenches and greater the casualties.

If we are to better understand, let alone improve, this messy world, we need differing views. This starts with humanizing the opposition. They are real people, and they, too, probably want a better world. Considering their views and experiences takes humility—we don't know what we don't know. At kitchen tables, community events and company water coolers, both/and thinking invites us to listen and learn from differing opinions. Our collective future is at stake.

How can both/and thinking be used in a practical way when navigating work situations?

Lewis: In our research, we found that employees who see tensions as opportunities and welcome differing views are more productive, creative and satisfied with their jobs. We've also found that effective leaders build both/and thinking into their organizations.

Consider Paul Polman, Unilever CEO 2008–2018. His vision, embodied in The Unilever Sustainable Living Plan, was to double profits through social and environmental responsibility. To do so, Polman constantly asked teams to discuss and work through their tensions. He invited diverse groups to share views and ideas, and all projects had to make positive financial and social impacts. Others see financial and social responsibilities as contradictory. Polman sees paradox.

What are some specific ways that both/and thinking can inform the challenges of diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) in the workplace?

Smith: DEI raises multiple paradoxes—honoring differences and finding similarities, ensuring equity and rewarding performance, recognizing people's varied contexts and needs and nurturing a collaborative, engaging culture.

For example, companies can achieve a more inclusive culture by helping employees bond with those similar to themselves. Through women, racial, LGBTQ+ and other resource groups, individuals feel more supported and confident, and create bridges to connect with the broader organization. Leaders are better able to attract and develop talented underrepresented minorities when they give direct, sometimes difficult feedback rather than avoid for fear of offending. Embracing DEI tensions takes trust, paired with shared values for inclusion and excellence.

What about with parenting? Can you share a specific example where it can be implemented? How can we teach our children to approach situations so they aren't only winner-take-all?

Smith: Recently, my husband and I fell into an either/or trap. Our son was unhappy at summer camp because his friends were in a different bunk. My husband wanted to call the camp and request a move. I wanted to wait and see if our son could find ways to be happier in the current situation. This tension surfaces a classic paradox—change the situation or change our mindset. In the end, change requires both.

Even knowing about both/and thinking—the issue led to conflict. We both felt sad that our son was unhappy. To deal with our emotions, our first reaction was to pick a side and defend.

It took us a few minutes to recover. We both cared about our son's happiness. We also shared goals. In the short-term we wanted him to have a good summer. Longer-term we wanted him to be resilient in difficult situations. We started discussing both/and possibilities. We talked to our son. We also learned how his camp counselors were experiencing the situation. Varied views opened new alternatives. In the end, our son made the decision. He felt comforted knowing that we took his issue seriously. He decided to stay put. He would start making friends in his bunk, while spending free time with his friends elsewhere.

Women have been told they can have both a career and a family for years. Can both/and thinking be applied here? How?

Smith: YES! But here's the rub. When it comes to career and family, women often say yes to everything. That is a recipe for burnout. Both/and thinking does not mean piling more and more on our plates.

Both/and thinking involves evaluating each side, then finding better ways to do both. What do we need for our career? What do we need for our family? Examining needs also helps us question what we don't need—learning how to say no or delegate those parts. Structures, what we call guardrails, help keep us from going too far either direction. For example, I have guardrails on my time. My family all unplugs from work and devices every Saturday, giving us time off and together. Some people might commit to no cell phones at dinner or family vacations. Guardrails will differ. The key is building and then using them.

Isn't there sometimes a right and a wrong way to do something? Is it possible to employ both/and thinking in all situations?

Smith: The other day I drove by a sign on the highway, "Text OR Drive—there is no AND." We agree!