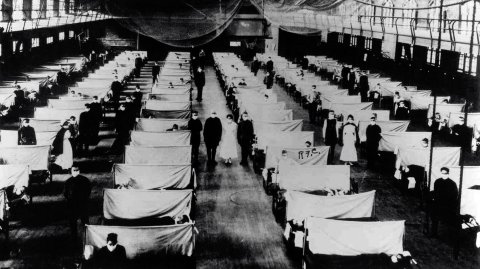

More than two-and-a-half years after COVID-19 first appeared, the world seems to have unofficially declared the pandemic over and done. It isn't yet, but with vaccines, antiviral medications and modern medicine, we can resume living our lives. Nevertheless, the effects of COVID will be felt on modern society long after the last PCR or rapid test result comes back positive. In his new book, Plagues and Their Aftermath: How Societies Recover from Pandemics by Brian Michael Jenkins (Melville House), terrorism expert and senior adviser to the president of the RAND Corporation Brian Michael Jenkins takes a look at past plagues—like the Black Death, which killed half the population of Europe, and the 1918 pandemic, which killed between 50 and 100 million people—to try to understand the future. In this adaptation from his book, Jenkins discusses how post-pandemic life will be marked by more than just long-lasting health concerns.

Today's pandemic will eventually fade—we are not sure how or when that will take place—but the normality we knew before will not return. What the post-pandemic world will look like is far from clear. Uncertainty may be its dominant feature. It is therefore important that we think about possible shifts in and potential shocks to our economic structures, political landscape and even mass psychology. Physicians talk about "long COVID," the range of ongoing, recurring or new medical conditions that can appear long after the initial infection: the concept has a broader application to society as a whole. And as we try to process what all this means, history can be a useful tool to help us understand what we might expect in the future.

Since the Middle Ages, it has been recognized that large-scale outbreaks of disease are dangerous and demand aggressive responses, drawing government into domains of activity that have traditionally been outside of political authority. Physical separation—keeping the disease away—has been the principal strategy. Travel and trade were restricted. People who were possibly exposed were quarantined—kept apart until they presented no danger.

As Frank Snowden noted in Epidemics and Society, these efforts, while understandable from a public health perspective, "justified control over the economy and the movement of people; they authorized surveillance and forcible detention; and they sanctioned the invasion of homes and the extinction of civil liberties [or what people saw as their 'rights' at various times in history]".

As in past epidemics, suspicions that government has exploited COVID-19 to expand its authority have been widespread. One commentator warned that lockdowns, "under the guise of a real medical pandemic," were turning the United States into "a totalitarian state." Resistance has often followed.

In Government We Don't Trust

The yellow fever epidemic that struck Philadelphia in 1793 intensified the partisan politics of the new American republic. Fearing a deep social revolution along the lines of the French Revolution, the Federalists blamed the epidemic on French refugees and pushed for a ban on immigration from France. Democratic-Republican merchants, who were more sympathetic to the revolution and who also benefited from trade with France, pushed back. The political differences extended to touting dubious remedies with Alexander Hamilton asserting that he had been cured by taking quinine and drinking wine. Similarly, the COVID-19 pandemic saw an extraordinary array of dubious or discredited preventives and treatments for the virus, including anti-parasitic drugs, "bombshell beads," chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine, copper water bottles, electromagnetic blocking patches and nanoparticles, energy healing sessions, indoor tanning, infrared radiation, oleander extract, ozone gas, dietary supplements containing silver and drinking cow's or one's own urine.

Recent research suggests that the 1918 flu had broad and long-lasting societal impacts. The social disruption caused by it significantly eroded people's trust, and the most fascinating finding—this lack of trust was inherited by descendants and persisted decades after the pandemic. Using long-term surveys of attitudes in America, the researchers found that those whose parents, grandparents and great-grandparents came from countries that suffered high mortality rates in the 1918 flu pandemic were significantly more mistrustful than those whose ancestors came from less-affected countries. This finding is consistent with more anecdotal evidence from the 19th-century cholera epidemics. It's very likely this will happen again.

Fraying the Fabric of Society

Psychologists blame the observed increase in antisocial behavior during the pandemic on prolonged isolation, which heightens anxiety, increases irritability, promotes aggression and diminishes impulse control. Essentially, people have shorter fuses. The effects may be hard to reverse.

Random violence appears to be unplanned outbursts in response to immediate circumstances, but it also reflects an underlying anger. Chronic stress provokes "displaced aggression"—anger released on someone who has nothing to do with the original source of the provocation. Reckless and nihilistic behavior also accompanies epidemics and it can, in turn, foster an erosion of ethics and a decline in respect for the law. It derives from the notion that there are no consequences to lawless or destructive behavior.

The consequences of the pandemic, the war in Ukraine and climate change have all contributed to uncertainty about the future—about whether humankind even has a future. The resulting distress may fundamentally change the way people think and behave in a seemingly more hostile and unpredictable world, the way they view the legitimacy of government authority, how we value life itself.

The number of murders and of mass shootings have both increased dramatically. Random acts of violence between strangers unconnected with ordinary crime or political ideology have increased. After remaining relatively stable for more than two decades, the number of homicides in the United States jumped from 16,669 in 2019 to 21,570 in 2020, a 30 percent increase. The number of homicides increased by another six percent in 2021—a combined increase of nearly 38 percent—the largest gain in more than 50 years.

Using the FBI's original definition of a mass shooting (an act of gun violence involving four or more fatalities), the average annual number of incidents roughly doubled since 2002.

Researchers also saw a trend toward increasing random violence—unprovoked attacks not resulting from ordinary crimes like armed robberies, and having no terrorism nexus, although sometimes targeting minorities. This trend preceded the pandemic, although it appears to have been accelerated by it.

These last two years have resembled the disorders seen during the Plague of Athens during the Peloponnesian War and the Black Death in the Middle Ages, which frayed the fabric of society. Just like now, the historian Thucydides noted that "Athens owed to the plague the beginnings of lawlessness." According to the 14th century Italian poet Giovanni Boccaccio, people in Florence behaved like animals during the plague. "Every man for himself" attitudes prevailed. Those who could do so fled for their lives. And just like now, the wealthy could remove themselves to distant residences; the poor had no such option.

The More You Have...The More You Have

In fact, the COVID-19 pandemic has exposed and exacerbated existing inequities. The super wealthy could flee to their ranches in Montana or doomsday retreats in New Zealand. Those with money to invest in the stock market did extremely well (at least until recently). The professional classes could safely work from home or wherever they wanted. The poor, such as those obliged to make the deliveries, died in greater numbers. Minority communities were often hit the hardest. The pandemic will leave a long tail of resentment and grievance.

The pandemics of the Middle Ages prompted the spread of conspiracy theories and bizarre beliefs, a phenomenon we see now as the latest, constantly mutating conspiracy theories go mainstream.

As in previous pandemics, COVID-19 has seen defiance to measures implemented to prevent the spread of a disease and protect populations. The pandemic has inspired civil disobedience and offers a model of resistance. National consensus will be even harder to maintain. Governing will be more difficult.

Scapegoating

Throughout the ages, pandemics have deepened existing prejudices and led to scapegoating directed against minority ethnic and religious groups as well as immigrants, often with official encouragement. The 1918 flu pandemic coincided with a major wave of immigration to the United States. Most of the newcomers were not from Great Britain and Northern Europe, as they had been in previous years, but instead came from Southern and Eastern Europe. Many were Jews. Similarly, the new Irish immigrants had been branded as importers of cholera in the early part of the 19th century. Immigrants arriving from Italy, Russia and the Austro-Hungarian Empire were seen as potential carriers of a variety of diseases, including typhoid, plague, infantile paralysis and tuberculosis. Ethnic hatreds and anti-foreign attitudes contributed to a massive expansion of the Ku Klux Klan in the 1920s.

COVID-19 has seen similar kinds of scapegoating. Extremist groups have exploited the situation to recruit followers and encourage genocidal fantasies. The so-called "China flu" has prompted a dramatic increase not only in social media abuse, but also physical attacks on Asian Americans.

Lingering Effects

Whether the issue is the global economy, the national economic outlook or one's own financial future; the environment or personal health; or the dangers of war, terrorism or crime—negative feelings, while wobbling from year to year, appear to have increased. Not all of society's ills can be attributed to COVID-19. America's disquietude preceded the virus, but the anxiety and anger were intensified by the outbreak.

We are still uncertain about the pandemic's long-term effects on physical and mental well-being. COVID-19 survivors are displaying a variety of lingering afflictions, including chronic fatigue, malaise, anxiety, depression, insomnia, brain fog and other cognitive changes. Medical researchers are exploring the relationship between the delirium experienced by many hospitalized COVID-19 patients and onset of dementia, already a major medical problem.

Social distancing and isolation have contributed to radicalization and extremism of some adults that will not easily be reversed. Students returning to in-person classes saw a significant increase in fights, riots and attacks on teachers and staff. School shootings have increased. We have a generation of kept-at-home toddlers who have been deprived of normal social interactions.

Post-pandemic society is a new, more perilous place where we are stressed, wary of each other, edgy and quick to violence. The pandemic has heightened distrust in American institutions, which many have come to see as dysfunctional, ineffectual, corrupt, even tyrannical. The pandemic revealed our declining ability to work together as a society. Political divisions deepened. The pandemic revealed deep distrust in science, in basic facts.

We don't know how long these effects will last, just as we do not know when the pandemic will be over. Historians still argue about the effects of the Black Death, which occurred nearly 700 years ago. There will be no announcements to herald the end of the pandemic. No victory parades. No sighs of relief. Pandemics are not slain like mythical dragons. They retreat, perhaps only temporarily, leaving behind a trail of death and destruction and an anxious population, uncertain when another variant will cause a new surge or a new disease might engulf the planet.

Adapted from Plagues and Their Aftermath: How Societies Recover from Pandemics by Brian Michael Jenkins by Brian Michael Jenkins, published by Melville House.