GE may have 'brought good things to life' over its 130-year history, but its rise and fall is a business cautionary tale for modern times

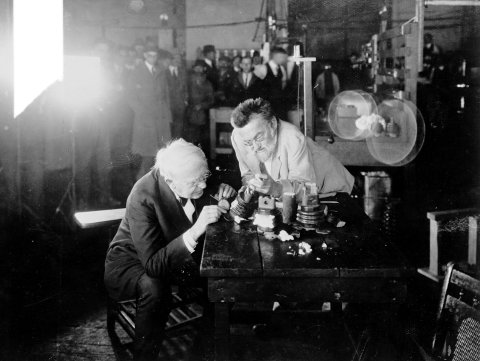

General Electric has a storied history and was the ultimate blue-chip stock. Electrical power pioneers Thomas Edison and Charles Coffin merged their enterprises in 1892 to become General Electric. The company grew into a household name, synonymous with everything from household appliances to jet engines to financial services, but 130 years after its rise, the huge conglomerate that was GE is being sold for parts. How and why this happened is the story bestselling author and financial journalist William D. Cohan tells in his new book, Power Failure: The Rise and Fall of an American Icon (Portfolio). In this exclusive excerpt, Cohan describes his meeting with 20-year GE CEO Jack Welch—and Welch's stinging rebuke of his successor, whom he blamed for GE's demise.

It was at the exclusive Nantucket Golf Club in Siasconset (often shortened to "Sconset") in August 2018 that Jack Welch, the octogenarian titan of American capitalism, invited me to lunch. We sat overlooking the ninth hole. Welch got around tentatively, with the help of either a cane or, as he called it, his "wagon," a three-wheeled, triangular walker. He'd had health problems for years, starting when he had a heart attack and quintuple bypass surgery in 1995. In 2009, he spent 92 days in a New York hospital battling a staph infection; he almost died. Never a physically imposing man, he now seemed even more gnome-like, a big head atop a shrinking body. But his mind remained razor sharp. And his personality remained a mix of infinite charm and biting candor.

During his nearly 20 years at the helm of the General Electric Company, now known simply as GE, Welch became a legend. Welch made GE the most valuable company in the world, in the same rarefied league now inhabited—depending on the day of the week—by the likes of Apple, Amazon, Google and Microsoft, or a combination of them all. He also made GE perennially the world's most admired company and himself the world's most admired CEO, although there were a few years, early in his tenure, when he was deemed the most feared CEO, a label he doesn't quite understand, despite his willingness to be self-critical. At different moments in his career, he was referred to as Teflon Jack for his ability to sidestep blame for disasters on his watch. He was also referred to as Neutron Jack for a few years, after he gained a reputation for ruthless cost cutting, eliminating lots of people and expenses while leaving buildings standing. He hated that name, too. By the time Welch retired from GE, on September 7, 2001, he was hailed as the CEO of the century.

There Was Always Golf

Jack was already sitting at the table at the Nantucket Golf Club when I arrived. The staff was expecting me, and I was ushered immediately to his table. He ordered the same lunch he always does, apparently: a small bowl of tomato soup, with a side of oyster crackers, and two chicken hot dogs. When he was GE's CEO, his lunch was always a turkey sandwich with lettuce, tomato and mustard on whole wheat. He drank a diet Slice. He used to work while he ate. "And he's a fast eater," said Rosanne Badowski, his longtime assistant.

Golf was one of the few constants in Jack's life. One way or another, there was always golf. You could learn a lot about someone playing golf, he liked to say.

Matt Lauer, the now-disgraced former host of the Today show, recalled years ago the many times he played golf with Jack and how he had what Lauer described as "the mental wedge" when it came to the game. "He had a wicked sense of humor, razor sharp," he told the now-defunct Talk magazine. "He loves to get in your head." He remembered one time when Jack was on the opposing team in the foursome, Jack walked up to him as he was getting ready to tee off. It was an important moment in the match. "You know," Jack said to him, "you're really losing your hair. You better make the most of your career 'cause it's going." Lauer thought to himself, "You son of a b****."

'I F***** Up'

Our lunch was the day before the start of the Dell Technologies Championship, the annual PGA event in Norton, Massachusetts. The famous golfer Phil Mickelson was at the Nantucket Golf Club for a practice round with some Wall Street bigwigs. At the next table over from us, Mickelson was having lunch with Bob Diamond, the former CEO of Barclays (the big British bank), who grew up on Nantucket, and with Paul Salem, one of the founding partners of Providence Equity Partners, a hugely successful private-equity firm. One after another, the three men came over to pay homage to Jack.

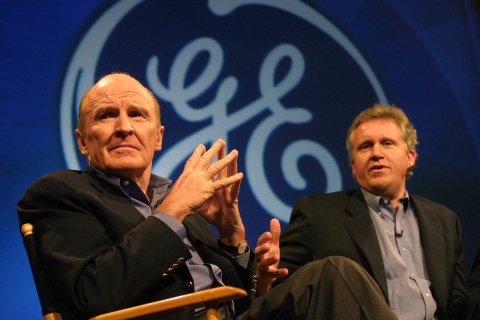

But Jack had more than golf chitchat on his agenda for our lunch. I was there to talk about what he had done to make GE the most valuable and most admired company in the world. But he had a few things he wanted to get off his chest first. What he really wanted to talk about was Jeff Immelt, his successor at GE. He seemed desperate to unburden himself about the guy and was already talking about him even before I could sit down. "I f***** up," he kept telling me, his squeaky Massachusetts patois getting crankier and crankier. "And I don't know why."

Jack had had no doubts about his decision to pick Immelt back in the day. But 18 years later, Welch's perspective on Immelt had changed dramatically. He had utterly soured on him and the job he did as GE's CEO. He repeatedly told me that Immelt was nothing more than a "marketer" who had effectively sucked up to him and the GE board to win their collective approval in the competitive, world-famous succession race. "He's full of s***," Jack said. "He's a bulls******."

"But Jack," I asked, "didn't you choose Jeff?"

Yes, he conceded he had. "That's my burden that I have to live with," he continued. "But people have been hurt. Employees. People's pensions. Shareholders. It's bad." There were tears in his eyes. "I f***** up," he said again. "I f***** up." I knew Jack had been disappointed by Jeff's reign atop GE, but I had no idea of the depth of his disdain for his successor.

Jack actually seemed not to like Jeff one bit. Hated him, in fact, and had decided he was not a nice guy and kind of a prick. He wanted me to know. "Reminiscing about this pisses me off every time," Jack told me. He then, and not for the last time, engaged in a bit of spin control: he told me how I should think about the story of the rise and fall of GE, once the world's most respected company—and admired conglomerate—now in the process of being dismantled. "I think comparing me to Jeff is not the winning angle," he said. "The winning angle is: How did Jeff do with what he got? How did I do with what I got? Jeff had eight years of free run with my foundation"—meaning the version of GE that Jack had left him on Jeff's first day as CEO, September 7, 2001—"until he started f****** around. We were going beautifully. He was CEO of the year with those assets that I gave him. Or my team gave him. He was CEO of the year."

Jack wasn't finished, not by a long shot. "He got a ton of money and he got good businesses," he continued. "And he played with them. That's the story."

Needless to say, Jeff Immelt has a very different view of Jack and the company that Jack left him to manage. Jeff saw problems everywhere that Jack had either ignored or obfuscated, through a combination of his incomparable bluster and effusive charm that wowed investors and Wall Street for nearly 20 years. Jeff saw himself on a mission to fix Jack's mistakes and prepare GE for the 21st century, the digital century. "Following Welch was certainly no easy task," Jeff told me with considerable understatement in our first interview, in Cambridge, Massachusetts. He would have much more to say.

After lunch, Jack offered to drive me in his Jeep Cherokee the three miles or so back to my Sconset house. The supremely efficient and solicitous valet parking crew at the golf club had by then fetched Jack's car, facing it out with the engine running and the doors open on both sides. I got in the Jeep and put on my seat belt. Jack sat on his seat belt. Since he wasn't wearing it, the warning bell kept going off. I urged him to put his seat belt on, if for no other reason than to make the noise stop. But Jack didn't care about the ringing. Nor did he care about his own safety, it seemed. "I hate those things," he told me.

Off he drove. When he got to the left turn out of the Nantucket Golf Club, onto Milestone Road, he did something odd. Instead of keeping to the right side of Milestone Road, as other American drivers do, he decided to drive in the middle of the road, with the Cherokee straddling the yellow line. Needless to say, the drivers coming toward us on Milestone were freaking out. One after another, they all pulled off to the right onto the grassy edge of the street, giving Jack full clearance to continue driving down the middle of the road. He didn't seem to notice.

Amid thoughts of what it might be like to perish in a vehicle driven by the greatest CEO of the American century, it struck me that Jack's vehemence at lunch in pinning the failure of GE on his successor wasn't just a display of ego or of his bitter disappointment in watching his legacy evaporate in real time. It was a reminder of what GE once was and why it matters. GE was never just another company. At different times during its 130-year run, it had been a leader in technological innovation and entrepreneurial drive. It had been a leader in helping people buy GE products, and a variety of other things, using GE's money. The generation and distribution of electricity? GE. The lightbulb? GE. The jet engine? GE. The X-ray machine? GE. The world's first radio broadcast? GE. The first home television sets? GE. The first electric cars? GE. Beneath the hood, GE had also been a crucible of corporate leadership, producing one leading executive after another who was capable of managing massive, far-flung global businesses across a variety of disciplines—including, among many others, Boeing, Honeywell, Allied-Signal and Warner Bros. Discovery—and could do so while making a tidy profit. Although many people forget, if they ever knew, GE was also a financial powerhouse, larger and more profitable than many commercial banks, investment banks, private-equity firms or hedge funds. GE embodied both the muscle of American business—entrepreneurial drive, inventiveness, financial legerdemain—and its weaknesses—unchecked egos, grandiosity, hubris and corruption. The story of GE's glorious rise and distressing fall is not just the story of a power company or a jet engine company or a TV network or a finance behemoth. It's a cautionary tale about hype, hubris, blind ambition and the limits of believing—and trying to live up continuously to—a flawed corporate mythology.

Adapted from Power Failure: The Rise and Fall of an American Icon by William D. Cohan with permission from Portfolio, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC. Copyright © 2022 by William D. Cohan