Updated | A 7-year-old boy with a rare and fatal skin condition that causes gruesome blisters has been given a treatment that is nothing short of a medical breakthrough. An entire new, genetically modified skin now covers most of his body.

The boy, which The Atlantic reported was a Syrian refugee named Hassan, had almost no skin when he arrived at a German hospital's burn center in June 2015. For months, doctors struggled just to keep him alive. Today, he's going to school, playing soccer and is not in danger from his disease.

A team of doctors genetically modified a small section of the child's own skin to correct a mutation associated with a devastating and fatal genetic condition. The boy still has the condition that caused him to lose his skin in the first place—junctional epidermolysis bullosa (JEB). But remarkably, almost none of the skin on his body does.

First defined in the 1920s and 1930s, epidermolysis bullosa is a disease best known by its gruesome blisters. The disease is caused by mutations in specific proteins that hold the layers of human skin together. There are different variants, depending on which protein is affected. Some hold the cells of the top (epidermal) layer together. Others do the same for the bottom (dermal) layer. Still others link the two; those proteins are the ones affected in JEB.

The severity of the disease can also range. Children whose mutations cause them to make absolutely no protein rarely survive more than a few weeks. But though skin blisters are probably the most visible symptom of the disease, that's not necessarily the deadliest part.

Blisters can become infected, as they did in this child. When a patient's skin is constantly compromised—and because the mutated protein can be found in other parts of the body too—there are other problems.

"When you don't have skin, you lose protein out of your skin, you lose blood, you become anemic," said Dr. Anne Lucky, medical director of the epidermolysis bullosa center at Cincinnati Children's Hospital. "A lot of these children develop problems in their airway—they get overgrowth of blood vessels and tissues, something called granulation tissue, which obstructs their breathing."

The protein is also necessary for the epithelial tissue in the lungs to work properly, which is often the lethal issue for newborns with this disease.

"These children just—they don't do well. The infants, they kind of dwindle," she said. For doctors and parents alike, it's difficult to watch. "Parents have some awful decisions to make."

New Treatment Hope

Until recently, treatment for JEB was about as sophisticated as putting a Band-Aid on a bullet wound. "The standard of care for these epidermolysis bullosa patients right now is just supportive. So we put bandages on the patients," said Dr. Peter Marinkovich, a skin specialist and researcher at Stanford University's medical school. JEB patients can spend tens of thousands of dollars every year just on bandages.

"They have a very miserable existence. They're just in pain every day," he said. "It's very difficult for the families for the patient, for the doctors even. We're all kind of frustrated that there's not more specific therapies."

After arriving at the hospital, this boy's doctors tried some of the more experimental therapies for the condition. They even tried a skin transplant from the boy's father. But nothing worked. "After two months, we were absolutely sure that we could do nothing for this kid and that he would die," said Dr. Tobias Rothoeft, one of the doctors who treated him.

Then the boy's team approached Dr. Michele De Luca, a gene therapy researcher at the Center for Regenerative Medicine at the University of Modena and Reggio Emilia in Italy. "He promised us he would give us enough skin to heal this kid," Rothoeft said.

And he did.

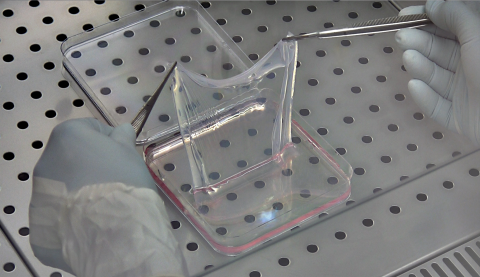

Using a virus, De Luca's team put a healthy version of the gene into some of the boy's own cells. The virus transformed the cells and gave them the ability to produce the cells required. Then they grew tiny samples into sheets large enough to cover 80 percent of the boy's body. Over the course of months, the team put the lab-grown skin on the wounds, allowing it to adhere. The child was released from the hospital in February 2016. The team that treated him posted details of his case and the treatment in Nature on Wednesday.

The basic technique—without the gene therapy—is already used for burn victims. And other researchers have done the same thing with far smaller patches. But the genetically modified, healthy versions of the boy's skin cells have been able to continue growing on their own and have extended beyond the areas of the original transplant. The skin has even begun to grow hair.

"He now behaves like his healthy siblings," Rothoeft said.

The amount of coverage achieved is astonishing. "For him, it was definitely a life-changing event," Marinkovich said. "He definitely has internal problems too. But to have the skin be replaced is just—it makes a huge impact in his life."

Marinkovich and his colleagues have been working on similar therapies for their patients in the United States. Next year, they'll begin Phase III trials—one of the last steps before submitting the treatment to the Food and Drug Administration for approval. De Luca is also running his own clinical trials.

This kind of treatment isn't without risk. In theory, Marinkovich said, there's a risk that a person's immune system could attack the new skin, or that the genetically modified skin might turn into cancer. (These kinds of patients are particularly prone to certain kinds of cancer, De Luca noted.) However, the boy's doctors haven't seen an immune response and will be watching the skin.

"The nice part about working on the skin is that if you develop a cancer, we'll have the chance to see it more readily because it will be exposed to the surface and we'll be able to cut it out and remove it before it develops," Marinkovich said.

The boy's doctors will continue to wait and watch as he grows up, as will Marinkovich and everyone else in the field—including, no doubt, other people with JEB.

"I think maybe you can't call it a cure," Marinkovich said. "But it's probably getting close."

This story has been updated with additional information about the boy who received the treatment.