Preliminary findings from a wide-ranging project on the health effects of bisphenol A appear to show that the chemical doesn't present major health risks, meaning current guidelines for exposure may be appropriate, according to the Food and Drug Administration. However, some scientists are warning that the results are far from final—and that new data may change the conclusions.

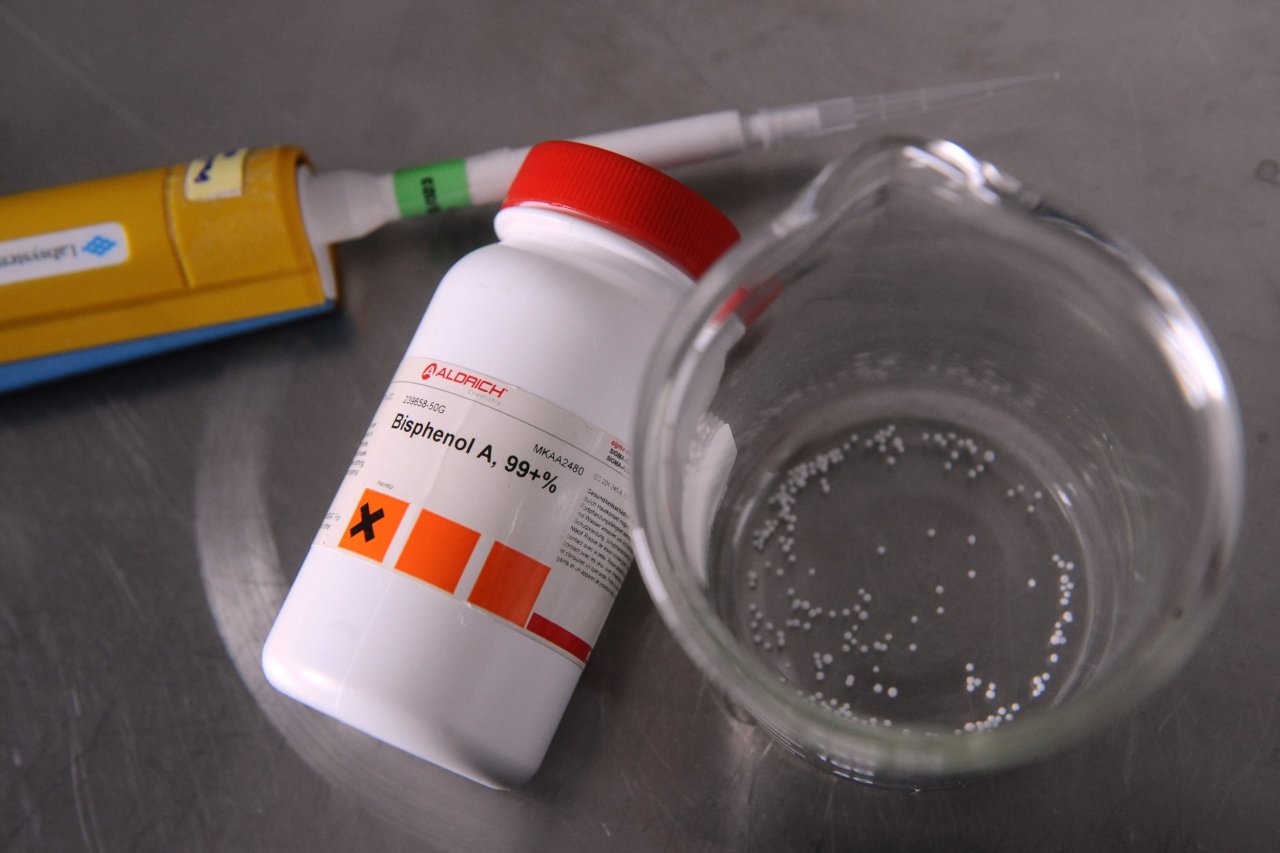

Also known as BPA, Bisphenol A is a chemical found in some canned food and plastic containers, among other household items. BPA's potential impact on human hormone levels has caused widespread concern: According to California's Environmental Protection Agency, BPA can cause "reproductive toxicity" in women.

The FDA's perspective has been that BPA is safe at the current levels people should be exposed to. "Based on FDA's ongoing safety review of scientific evidence, the available information continues to support the safety of BPA for the currently approved uses in food containers and packaging," the agency's website states.

The new results come from a research program known as Consortium Linking Academic and Regulatory Insights on Bisphenol A Toxicity, or CLARITY-BPA. The program is a joint effort of the National Institutes of Health's National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences and the FDA's National Center for Toxicological Research. The National Toxicology Program (NTP), a division of the NIEHS, released a draft research report from the study on Friday.

Throughout the two-year study, researchers checked for signs of the test rats' sexual maturity and for potential disease in the animals' organs. The lowest dose was designed to create blood levels of the chemical that are not much different than the upper range seen in humans, Dr. John Bucher, the NTP senior scientist, told Newsweek, adding that the study used a wider range of doses than a typical toxicology study.

The FDA released a statement about the new report from Dr. Stephen Ostroff, the deputy commissioner for foods and veterinary medicine. "Overall, the study found 'minimal effects' for the BPA-dosed groups of rodents," he stated. However, one group of mice had more mammary gland tumors and the findings hadn't been reviewed by outside experts, he noted on Friday afternoon.

Despite these caveats, the statement was interpreted by many to mean that the report shows BPA is "probably safe," " unlikely to be harmful," or may not be "much of a threat."

However, this report is just one part of the CLARITY project—and the academic scientists involved in the second half are concerned about the way the government has presented the results so far.

"It was disappointing to me to read that [statement]," said Gail Prins, a researcher at the University of Illinois at Chicago who is looking for possible links to prostate cancer as part of the CLARITY project. "Not only did this report come out, but they immediately released it to the news media and made a statement to the news media."

She added: "I'm not saying what they did was bad work. [The results] are valid, but they are not complete." (The Endocrine Society also issued a statement on Monday afternoon expressing "disappointment" with the FDA's statement.)

The measurements the FDA used for this first report, Prins noted, are very basic: the weight of the animals and their organs as well as the way the animals' organs looked. "These are the types of endpoints that toxicology has been doing since the mid-20th century," she said, adding that her academic colleagues will be using far more advanced techniques. She said those academic analyses do seem to be showing health effects, even at lower levels.

This first report will go through a peer-review session on April 26. The public will be allowed to submit comments and attend the meeting, space permitting. The final report is expected to be released in August, though the final conclusions aren't likely to be out until August 2019.

As Prins put it: "We're at halftime right now."