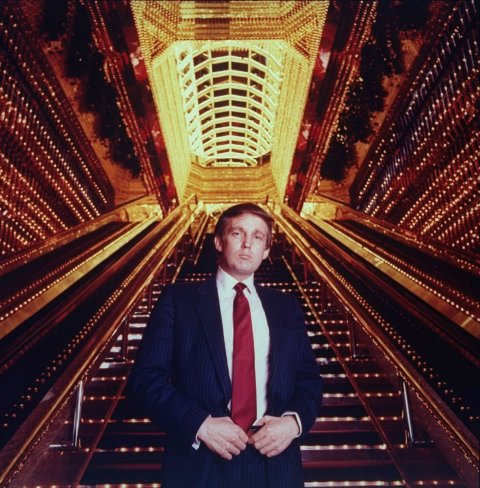

In the summer of 2016, Donald Trump sold a pair of New York City condos to his son Eric for $350,000 a piece—less than half their listing prices. In doing so, two tax lawyers wrote in The Washington Post, he may have committed fraud. It wasn't the first time someone has accused him of such a crime. Years earlier, as the city and state audited his 1984 tax returns, Trump failed to provide documentation for $600,000 in deductions. The case went to trial, where his tax preparer testified under oath to have never signed the return. Yet the tax preparer's name was on the document. Assuming he was telling the truth, the only possible explanation, according to Trump biographer David Cay Johnston, was that someone had photocopied his signature and pasted it on the return. (Trump lost both cases and was later fined by a state judge.)

Since the late 1970s, Johnston and other Trump biographers—including the late Wayne Barrett—have documented many instances of what they call the New York real estate mogul's ethically and legally questionable business dealings. (The White House and the Trump Organization did not respond to requests for comment in time for publication.) And though Trump has lost in court, he has shown extraordinary skill at shutting down investigations. "He knows when to run to the cops and rat out people," says Johnston, author of the recent book It's Even Worse Than You Think: What the Trump Administration Is Doing to America. "He knows how to use the court system to cover up what he's done by making a settlement on the condition that the record be sealed. He's masterful at this."

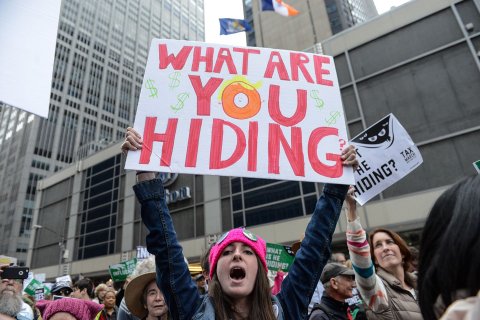

Political success—and the added scrutiny it brought to Trump's life—have not changed his style. Since his election, legal scholars, former prosecutors and other critics have argued that the president's flagrant disregard for unwritten norms is degrading American democracy. Their list of examples is long: Trump broke with 40 years of presidential tradition by not releasing his tax returns. He has made a multitude of false statements and attacked journalists for doing their jobs, weakening the public's ability to agree on facts. He has also ignored the appearance of conflicts of interest, retaining ownership of various properties, where foreign and domestic lobbyists fork over big money for the chance to meet him. Trump's done all of this while facing a variety of legal challenges—including one from New York Attorney General Eric Schneiderman, who's investigating his charity after it admitted violating IRS rules when it used foundation funds to benefit Trump or his family.

The most perilous—and high-profile—challenge Trump has ever faced comes from special counsel Robert Mueller. His probe is supposed to ferret out whether Trump's campaign coordinated with Russian electoral interference operations. But it is widely assumed to be much broader. Mueller is investigating whether Trump obstructed justice when he fired FBI Director James Comey in May 2017, and his team, packed with experts in financial malfeasance, is also believed to be looking at money laundering charges.

The president's critics certainly hope so. Once they recovered from the shock of his election, they put their faith in the U.S. legal system to stymie Trump's worst impulses and hold him accountable. Since last summer, a common refrain, especially among progressives, has been "It's Mueller time."

Much of what can charitably be called irregularities in Trump's business past are public, but he has always managed to negotiate or settle his way out of trouble. Now, Mueller's lawyers with subpoena power will be able to go far beyond what Johnston and other investigative journalists have already turned up. With three members of Trump's campaign (Rick Gates, Michael Flynn and George Papadopoulos) cooperating with the special counsel—as well as another, former campaign manager Paul Manafort, under indictment and facing decades in prison—the president has never looked more vulnerable.

Yet some analysts worry that Trump—if he in fact committed a crime—could still get away with it. The president is a singular figure in the annals of American politics, and his critics fear that the U.S. legal system is not up to the challenge, or that perhaps only changes in politics and policy can actually impede someone like Trump.

Since the 1980s, there have been four special investigations into presidents. But only one—Bill Clinton's—led to an impeachment (and just in the House of Representatives). "Our Constitution was not created to deal with someone with Donald Trump's character," says Jason Johnson, a political scientist and MSNBC contributor. "This is the greatest challenge to constraining him with the law or the Constitution or controlling his behavior."

As Trump's presidency—perhaps one of the great political dramas of all time—plays out, the real cliffhanger isn't just whether the Russians coordinated their efforts with the GOP nominee. What's also keeping audiences glued to their screens is the almost unbearable suspense of trying to decide what they're watching: A redux of All the President's Men? O.J. Simpson in the white Bronco, crawling down the 405? Or something more akin to Catch Me if You Can?

Bullying, Harassment and Playing Pols

Many of Trump's tactics are not uncommon in New York real estate development—nor are they all technically illegal. Take bankruptcy, for instance. Most people call it an embarrassment, a stain on their credit. But Trump—whose companies have filed for bankruptcy six times—frames them differently. He views Chapter 11 as a smart business tool that's allowed him to run up massive debts, stay afloat and avoid paying taxes. "I have used the laws of this country...to do a great job for my company, for myself, for my employees, for my family," he said during the first Republican presidential debate in the summer of 2015.

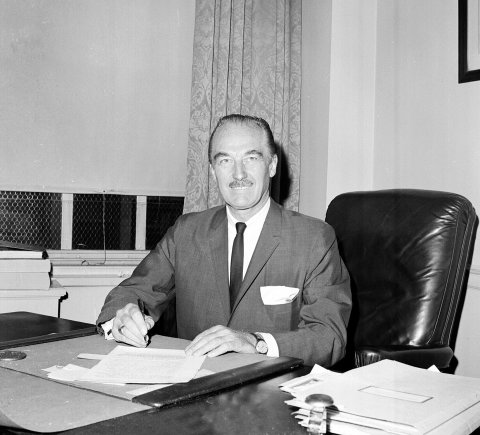

It's not just bankruptcy. The president is a master of finding loopholes to smash norms and laws, and he learned from the best, according to Johnston, the Trump biographer. His father, Fred, was allegedly a mob-connected developer in New York's Queens who frequently skirted regulations. In 1954, the Senate Banking and Currency Committee hauled him down to Washington to testify about overcharging a federal housing program for the middle class by about $4 million. The elder Trump not only didn't deny it but flummoxed his interrogators when he told them his behavior was within the letter of the law, if not the spirit, according to testimony and news reports on the incident cited by numerous Trump biographers.

Once he moved from Queens to Manhattan, the Donald was further schooled by Roy Cohn, an infamous lawyer who worked for both Senator Joseph McCarthy and the mob. Cohn's legal style was to never give in and to punch back at every opportunity. Trump was an apt pupil, his biographers say, and he's always relied on a heavy assist from his attorneys.

But Trump does have an instinct for homing in on an opponent's personal flaws, emotional buttons, potential scandals or hidden weaknesses. One lawyer—who asked not to be identified because he is still practicing in New York—worked with Trump on a dispute with a partner. The real estate mogul didn't pay much attention to the fine points of the law. But in meetings, he would disclose or suggest potentially embarrassing information about the partner. He was uniquely placed to identify where the partner—like him—had been sidestepping norms or finding loopholes. Trump's threats worked, and the partner settled.

Another Trump tactic has been to stall. As a businessman, he has run out the clock or evaded four grand juries, usually until the statutes of limitation ran out, according to Johnston. In 2016, six years after Trump University students first sued him over fraudulent claims made by the school, he bragged on Morning Joe that he could settle if he wanted to, but wouldn't on principle. It's quite possible that if he hadn't been elected, Trump would have continued to fight plaintiffs who alleged they had maxed out their credit cards and received nothing of value in return. Instead, he settled for $25 million.

Perhaps Trump's most common tactic, however, is the harassing lawsuit. Average Americans see civil suits as expensive and nettlesome. Trump sees them as a useful cudgel, his biographers say. The record of Trump lawsuits is long, but to name a few highlights: He sued Deutsche Bank in 2008 for $3 billion in a dispute over a $40 million debt he owed. The bank countersued and eventually started loaning Trump money again. He sued a Miss Universe contestant, Sheena Monnin, for $10 million after she called the contest rigged (Recently, pageant officials appeared to confirm this to The New Yorker's Jeffrey Toobin.) Trump won a $5 million settlement in a forced arbitration against the 27-year-old (Monnin later sued her own lawyer for malpractice; the attorney eventually settled). He also sued Schneiderman for $100 million after the New York attorney general called Trump University "straight-up fraud." That suit was thrown out, but not before Trump tweeted that Schneiderman looks as if he wears eyeliner.

Some of Trump's lawsuits and legal threats verge on bullying, says conservative legal scholar Richard Epstein. In 2016, when Trump was running for president, he persuaded his lawyer Marc Kasowitz to demand The New York Times retract its story about past sexual misconduct partly because some of the women waited years and even decades to come forward. Epstein, in an open letter to Trump before the election, called that claim "one of the dumbest demand letters in the history of defamation law."

Trump has also used the law to frighten potential adversaries into silence or retreat, biographers say. The Trump Organization, for instance, often forced consultants and employees to sign nondisclosure or non-disparagement agreements (NDAs). At least one of his ex-wives, Ivana, signed a post-nuptial contract that contained a silencing clause. The president may have used money to get his way in other instances too. In February, Trump Organization attorney Michael Cohen admitted paying $130,000 to porn actress Stormy Daniels during the 2016 campaign, which a bank reportedly flagged as suspicious to the U.S. Treasury Department. Cohen said the money came from his own pocket. He refused to concede that it was hush money, which many assume Daniels received to keep her from talking about her alleged relationship with Trump a few months after Melania gave birth to Barron in 2006.

Personalized attacks, NDAs, threats and money may work for small jobs like disposing of business partners or quieting chatty paramours. But for bigger jobs, like erecting skyscrapers in midtown Manhattan, Trump has reportedly deployed another tactic: playing politicians—not politics. For decades, Johnston and others wrote, New York pols were like Play-Doh in Trump's hands. The Trump strategy of currying influence with lawmakers to grease business deals dates back a generation to his father's playbook—which is why Trump's first wedding was chockablock with New York political fixers and pols, including a former mayor, Abe Beame.

Over the years, Trump has reportedly wrested massive tax breaks from City Hall for his buildings and got regulators and lawyers to perform feats of administrative jiujitsu so he could get what he wanted. Trump's first great project in the Big Apple was rebuilding a hotel at Grand Central Station in the 1970s, when New York City was crime-infested and broke, its leaders desperate. Trump cut a deal in which a tax-exempt city agency bought the site of the hotel. Then the agency leased it back to him for $1 a year, along with a 40-year tax break that had, as of 2016, cost the city $360 million. Even with that largesse, Trump blew off one of the requests New York had attached to the tax breaks—that he build subway entrances on both sides of the hotel, constructed over one of the busiest transit hubs in the region. Eventually, he built one, not the two he'd agreed to. Having bent the city to do his bidding, he then sued it for more tax breaks, demanding and gaining one for Trump Tower, his signature building on Fifth Avenue. Two decades later, in 2001, in a lawsuit that lasted through two mayoral administrations, he won a similar tax break for Trump World Tower, a building with some of the city's priciest condos. The tax breaks for those two projects reportedly totaled $157 million.

As Alicia Glen, Mayor Bill de Blasio's deputy mayor for housing and economic development, told The New York Times: "Donald Trump is probably worse than any other developer in his relentless pursuit of every single dime of taxpayer subsidies he can get his paws on."

The Ultimate Revenge

As effective as Trump's tactics have been, his critics have maintained faith that the legal system can prevail. They believe that Trump has likely violated the law, not to mention breaking agreed-upon norms, and that the American people simply need to be patient and vigilant and let the system take care of him. Norm Eisen, President Barack Obama's top ethics lawyer, is one of them. He's now part of the government watchdog Citizens for Responsibility and Ethics in Washington, which filed a now-dismissed emoluments lawsuit against the president. "To Donald Trump, litigation is just another business tool to harass." he says. "That won't work as president. Mueller is the ultimate revenge."

The president's detractors like to compare Trump to Richard Nixon and predict a similar fate for him: In one way or another, they believe, he will have to leave office prematurely. Russiagate, they say, is just a Watergate sequel, with an extra dollop of international intrigue. But Trump is not Nixon, and 2018 is not 1973. Nixon was a politician who took the old-fashioned route to the White House, through party politics. Trump is not a politician and has never held elected office. And he has rarely—until he got elected—been held legally accountable for his penchant for exaggeration, among other things.

Nixon, of course, lied craftily. About the Vietnam War. About the air war on Cambodia. About whether or not he was a crook. Trump, his critics say, is more of a bullshit artist, spewing statements that are often easily disproved. Whether out of instinct or part of a calculated strategy, he bends truth to fit his own desires. Trump's exaggerations as president have been tabulated and provoke almost daily squeals of outrage. One could fill the pages of this magazine with his false statements, from accusing Obama of wiretapping him to promising that Mexico would pay for a border wall. As of January, The Washington Post had clocked more than 2,000 lies, and the number keeps rising.

The tactic has served him well in the court of public opinion, but not in court. During one libel case he brought against biographer Timothy O'Brien, Trump submitted to a deposition. The result: O'Brien's lawyers proved that Trump had told 30 lies about his finances and deals. Those lies were not illegal, and he confessed to them under oath. He lost the case.

Alternative facts probably won't fly in an interview with Mueller either. Trump has said he looks forward to talking to the special counsel, but his lawyers are advising against it. If past practice is any indication of how he'd behave, it's possible that he will simply cave when confronted with the truth, as he did in the O'Brien lawsuit. "If the lawyers have to take him down to the basement of the White House and physically chain him up to prevent him from talking to Mueller, I would recommend that," the conservative commentator Ben Shapiro recently joked on Fox.

But Trump's alternative facts do present a serious challenge, some observers say—not just to faith in the legitimacy of law enforcement but to the rule of law itself. Every time Trump calls news articles he dislikes "fake news" and promotes conspiracy-mongering broadcasters like Alex Jones of Infowars, he chips away at the foundation of democracy, which requires an informed public and respect for objective reality. As Martin London, one of the lawyers for Nixon's first vice president, Spiro Agnew (who pleaded no contest to felony tax evasion and resigned after a corruption probe), wrote for Time recently, "Without strict adherence to concepts of truth and fact, there can be no organized system of justice."

Preet Bharara, former U.S. attorney for the Southern District of New York, has similar concerns. "This is a person who does not believe in speaking the truth in any context and virtually in any moment," he said recently on author Sam Harris's podcast Waking Up. "He has a lot of power and is using the bully pulpit…in a particular way that no one has used it before."

Conspiracy Theories and Presidential Pardons

The president has been a plaintiff or defendant in 4,095 lawsuits, according to research by USA Today. His companies have been engaged in legal battles over taxes almost every year since the 1980s. Those numbers, coupled with Trump's skill at manipulating the law, evading norms and creating disbelief in once-stable institutions, have led some critics to raise the question: Will he just keep getting away with it?

Even before his inauguration, President-elect Trump announced his intention to flout one of the most basic norms in Washington: avoiding the appearance of conflict of interest. On January 11, at his first post-election press conference, he said the presidency was not sufficient reason to divest from his hundreds of businesses. "I have a no conflict of interest provision as president," he announced. "I could actually run my business and run government at the same time."

Later in the press conference, he gave the podium to one of his lawyers, Sheri Dillon, who announced, "President-elect Trump should not be expected to destroy the company he built." She added that he would separate himself from the management of the company and that his family would "take all steps realistically possible to make it clear that he is not exploiting the office of the presidency for his personal benefit." Dillon also said, "No new foreign deals will be made whatsoever during the duration of President Trump's presidency."

Today, Trump remains a beneficiary of his Washington hotel property, as well as his other businesses. Meanwhile, his sons have carried on doing business in countries whose leaders meet at the White House or Mar-a-Lago with the president—a possible recipe for corruption. A few months after Trump's daughter Ivanka, a presidential adviser, headlined a women's entrepreneurial seminar in Hyderabad, India, in November, Don Jr. was in a private jet, winging his way east to close a deal on Trump-branded skyscrapers in that country.

Back in Washington, foreign dignitaries and lobbyists trying to do business with the White House have lined up to pour money into Trump hotels and golf courses, seemingly to curry influence. As a result, in July 2017, the U.S. government's chief ethics lawyer, Walter Shaub, resigned in despair. A federal employee tasked with making sure top government officials behave ethically, Shaub was powerless because the president is legally immune to conflict of interest laws that apply to other federal employees. A president's business is so vast that theoretically, the thinking goes, anything he does could be a conflict. Trump, predictably, exploited this loophole.

Since he moved to Washington, the president, analysts point out, has resorted to other pages of his old playbook. Besides the president deriding Comey—to Russian Oval Office visitors, no less—as "a real nutjob" after he fired him, Trump's team has used the intimate lives of lesser-known individuals involved in the Russia investigation to discredit the FBI. First, they focused on the political allegiances of former Deputy Director Andrew McCabe, whose wife, Jill ran for state office as a Democrat, until McCabe retired early. The Trump administration also seized on private, anti-Trump texts, ferreted out by the Justice Department inspector general, between FBI agent Peter Strzok and his mistress, former FBI attorney Lisa Page. With those two officials besmirched as part of an alleged anti-Trump "deep state" conspiracy, the president's team continued attacking the bureau.

Along the way, Trump has found a new high-powered pol to help him: California Representative Devin Nunes, the House Intelligence Committee chairman. With his access to classified national security information, Nunes has become the congressional point man for what critics call Trump's disinformation campaign. He has led the accusations on Capitol Hill against Obama and Democrats in the Justice Department. Nunes has been key in blaming Democrats for the president's Russia troubles and pushing the deep state conspiracy line. "None has ever been so partisan as the current...chair," Loch Johnson, a leading intelligence historian at the University of Georgia, tells Newsweek about Nunes. (The congressman didn't respond to a request for comment in time for publication.)

Many expect the president to run out the clock as well. Among the lawsuits filed against him in office is one alleging defamation, brought by Summer Zervos, one of the at least 16 women he has called liars for accusing him of various degrees of sexual misconduct, and another case, charging incitement to violence, brought by protesters who were assaulted at a Trump campaign rally in Kentucky. Both cases are currently halted as appeals courts grapple with arguments about whether the plaintiffs have standing to sue a president. Lawyers don't expect those cases to proceed for many months, if not years. If Trump's lawyers challenge a request from Mueller to depose him, analysts say, that would spark a similarly time-consuming legal chain of events that could take him to the end of his term.

During his year in office, Trump has even employed a new tactic that comes with the job: the presidential pardon. He has already used it once, on Arizona Sheriff Joe Arpaio, whose anti-immigrant policies and Obama birther conspiracies were Trumpian long before the Donald rode the escalator down to Trump Tower lobby and announced his candidacy. (Arpaio had been convicted of criminal contempt of court for disobeying a federal judge's order to stop racial profiling of immigrants.)

In theory, Trump could pardon everyone involved in the Mueller case too. That act would be shocking and provocative, critics say. But it is legal.

Short Fingers of the Law?

Since Ronald Reagan was embroiled in the Iran-Contra scandal in the mid-1980s, every U.S. president except Obama has drawn a special investigation. And these probes have not had much punitive effect. The independent (now special) counsels during the administrations of George H.W. Bush (he pardoned Defense Secretary Caspar Weinberger in the Iran-Contra scandal) and George W. Bush (Vice President Dick Cheney's attaché Scooter Libby went to prison for leaking) all left the presidency intact. Even Clinton wasn't booted from office.

Anti-Trumpers believe they have a backstop for Mueller should he fail or be fired: Schneiderman, the New York attorney general. And while he's never said that he could take that role, Schneiderman believes the law is capable of dealing with Trump. "He's deployed the same tactics over and over again during the course of his business career," Schneiderman wrote in an email. "Now that he's president he faces very different legal challenges and I do not think he can rely on the same playbook."

A president can't pardon state charges, but it is not clear that a state attorney general—or anyone—can charge a president. Bharara says the legal consensus is that prosecutors can't. But a memo from the office of Ken Starr, the independent counsel who investigated Clinton, says otherwise. "It is proper, constitutional, and legal for a federal grand jury to indict a sitting president for serious criminal acts that are not part of, and are contrary to, the president's official duties," the Starr office memo states, according to The New York Times.

The Constitution does offer a possible solution to a president's conflicts of interest: the obscure emoluments clause. Article I, Section 9, Clause 8 of the Constitution prohibits the federal government from granting titles of nobility, and restricts members of the government from receiving gifts, emoluments, offices or titles from foreign states. After the president was inaugurated, anti-Trump forces immediately filed three emoluments cases, alleging that they were injured by his conflicts of interest. A judge has thrown one out already, because the plaintiffs lacked standing—they couldn't prove to the court that they were injured. Two more, one brought by Washington, D.C., and the state of Maryland, and another by Democratic members of Congress, are still proceeding.

Civil society lawyers in Washington say the only real solution to Trump-style conflicts—like his earning money from a hotel down the street from the White House—would be a new statute based on the emoluments clause. Without laws, they say, norms are breakable. "Even when these laws are not effective, there was always the shame factor," says Washington lawyer Paul Ryan (not to be confused with the House speaker), legislative director with Common Cause, one the nation's largest government watchdog groups. "But Trump is dancing on the third rail. He's also put Congress—which is also immune from being fired for conflicts—on the third rail with him."

Federal lawmakers are not racing to pass such legislation. Unlike Trump, members of Congress are subject to conflicts of interest laws, but there is no federal requirement that they recuse themselves from their businesses. That is one reason some of them might be reluctant to press the issue. "Congress has never passed a statute to effectively implement the emoluments clause," says Ryan. "And perhaps Congress has never passed such a law because this provision of the law has been respected and never violated. Oftentimes, these things change in the wake of scandal."

Legal experts give the two remaining emoluments clause lawsuits a remote chance of succeeding. But they point to a downside to the tactic: The clause has never been tested in practice, so if Trump manages to get them all dismissed, he will have set a precedent making any president who comes after him immune to the sole existing prohibition on conflicts of interest.

That possible result is one reason why Epstein, the conservative legal scholar, says statutory or policy changes aimed at Trump's style and tactics are problematic. Outliers like Trump will always take advantage of small variations in the way the law is interpreted or applied by courts. But changing the rules to make a "Trump-proof" system could eventually "backfire on the good guys as well" by adding new layers of rules and statutes that further bog down a system that libertarians like Epstein find cumbersome.

Maybe, but the legislative reaction to scandal is to make more laws. After Watergate, Congress enacted a series of government reforms. Civil society lawyers hope a similar backlash will erupt post-Trump. Some signs of that are already apparent: This year, in direct response to the president, a few state legislatures are considering laws requiring a presidential candidate to disclose his or her tax returns in order to appear on the state ballot.

Another Trump critic, Austin Evers, founder and director of the nonprofit American Oversight, which has been bird-dogging the Trump administration with public records requests, agrees that politics, not law, must ultimately be responsible for addressing matters like the president's conflicts of interests. He predicts a new class of politicians elected in the 2018 midterms will enact such reforms. "The Constitution doesn't have a human resources department, and Trump is a consequence," he says. "The only mechanism to remove someone from office for that conduct is to draw on his own sense of accountability, and he doesn't have one. We have seen the moment [for electoral revolt] already in the special elections, but the big one is next November."

Politics may ultimately have to deal with Trump, says Elizabeth Holtzman. A former New York representative who once served on the Watergate committee, she doesn't believe it's necessarily up to the law to deal with this president. "I have no respect for Trump," she says. "His election has been a disaster. But I can't agree with the characterization that he has wriggled out of everything. It may be that the laws were not written or the evidence was not there."

Even if Mueller's investigation leads to findings against Trump, the law still might not take him down. The last special investigator to gather evidence against a president— Starr—decided not to charge the commander in chief. He handed his findings over to the Justice Department, which shared them with Congress. If Mueller does the same, Trump's fate becomes a matter of politics.

But there's still no guarantee that this hyper-partisan Congress will act, especially so long as the GOP base strongly supports the president—and retains a majority in both chambers. In June 1973, it was a Republican, Tennessee Senator Howard Baker, who famously asked: "What did the president know, and when did he know it?" And though it took a dramatic series of resignations and firings, and the release of Oval Office tapes proving Nixon's guilt, to get him to step down, that question, from a single Republican, is an enduring symbol of respect for the Constitution over partisan politics. "Watergate strengthened the United States," Holtzman says. "It showed the rule of law worked, that the rule of law is above any political party."

Trump is unlikely to resign anytime soon. And Republican members of Congress during the Nixon scandal were not just a different generation from their descendants today—they were a different breed, with a different level of partisanship, Holtzman says. "What the American people are seeing today," she adds, "is that the rule of law and Constitution are not more important than 'What's in it for me?'"

Which is perhaps a fitting theme for Trump's political reality show, however it may end.