Mao Xinping rakes through the undergrowth in a pine forest on a hillside in China's Yunnan province. After only a few minutes, he finds what he is looking for—a handful of golf-ball-size black truffles. Just to show that this is no fluke, he wanders farther into the forest, past clumps of wild ginger and the occasional marijuana plant, to repeat the performance. "I get paid 1,000 renminbi a kilo [about $150] for them, which is a large part of my income. No one eats them here—we used to just feed them to the pigs," Mao says. Farmers here began harvesting truffles 20 years ago; now Yunnan produces 200 tons of tuber indicum, or Chinese black truffles, and exports much of that to truffle-hungry diners overseas.

A growing number of wealthy Chinese diners have also been seduced by the musty, morel-ish allure of these earthbound fungi. With me as I visit the local producers of several high-end ingredients during a recent trip to China is Terrence Crandall, executive chef of the Peninsula Hotel in Shanghai, who wants to encourage more awareness of the quality produce available in China. Many affluent Chinese consumers have embraced foods that are not traditionally Chinese, and chefs like Crandall are increasingly incorporating them into high-end menus. Chinese entrepreneurs and established companies are also taking advantage of the increasing demand for luxury foods, both imported and Chinese-grown.

Crandall acknowledges that the Yunnan truffles Mao finds in the forest are far from the quality of Périgord truffles (Tuber melanosporum)—France's finest. "One of the problems is that all of these truffles are on state land, so it's first come, first served—which means they are usually taken before they are fully mature," Crandall explains. Even though the quality of Chinese truffles may not be world-class, some dealers in Europe mix them with top-quality local varieties; the Chinese tubers are physically impossible to differentiate from European truffles and cost a fraction of the price.

Crandall explains that truffles are far from the only delicious fungi to be found in Yunnan. The province, in the south of the country, is home to nearly 30 types of edible mushrooms, including superb morels, boletus and matsutake, which are highly sought after in Japan. China is already the world's largest producer of fungi and the third-biggest exporter after Poland and the Netherlands. Don't be surprised if you see Chinese mushrooms coming to a place near you soon—Yunnan alone expects to export more than $1.5 billion worth this year.

Chinese truffles, along with the country's nascent but rapidly growing wine industry, may never rival the very best foreign alternatives, but there is one luxury food product the Chinese are definitely in line to dominate—caviar.

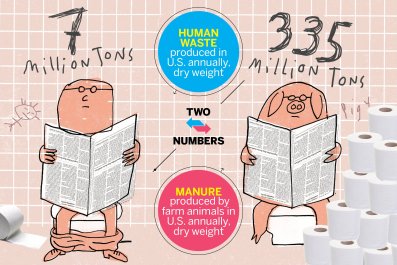

Gourmets have long prized the unfertilized roe of several species of sturgeon. Unfortunately, it is necessary to kill these fish to harvest the caviar, which is usually between 10 and 12 percent of the weight of a fully mature sturgeon. More than 90 percent of the world's caviar once came from the Caspian Sea, but due to overfishing, pollution and political instability, regulating production was vital. Since 2008, there have been strict quotas and then a worldwide ban on wild caviar production according to a treaty, the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora. This has led to a profusion of farmed varieties in more than 50 countries, from Saudi Arabia to Bulgaria. Some of these countries are producing delicious farmed caviar, but serious aficionados still hanker after the taste of the wild Russian and Iranian varieties from the Caspian.

Wild caviar production was around 1,000 tons per year in the mid-1980s, and while farmed caviar worldwide is catching up, it has only just passed a total of 200 tons. The heartland for caviar production in China is in one of the most exquisite and unspoiled destinations in the country—the vast Thousand Island Lake, 250 miles southwest of Shanghai. This artificial lake was created 50 years ago to provide hydroelectricity. There is no industry nearby, and nearly 90 percent of the shoreline is natural forest, conditions that have made the lake ideal for farming healthy sturgeon.

The Kaluga Queen caviar company, based at the lake, produced its first caviar in 2006. Five main species of sturgeon are being reared in the Thousand Island Lake, all in huge subterranean cages, which are lowered into deeper water during the hotter summer months. Because of poaching and pollution in the Caspian Sea, plus the worldwide ban on catching sturgeon in the wild, Russia, Iran and the other countries that surround the Caspian are way behind in their farming practices, as they wrongly assumed the worldwide bans would soon be lifted and therefore lost time in creating farmed stocks. It takes at least eight to 10 years for some sturgeon species to mature, while beluga, the rarest and most expensive species of them all, can take 12 to 18 years to grow to full size before they are caught, killed and the caviar eggs removed from their bellies.

When I visited the lake recently, I traveled by speedboat from a dock across the still surface for several miles to reach the sturgeon farms. The only sign of the farms is a series of narrow walkways surrounding what appears to be open water. Inside big steel pens are hundreds of large, shark-like sturgeon, many well over 6 feet in length. There are 50,000 sturgeon slowly reaching maturity before being taken several hours away in water-filled trucks to a processing plant in the city of Quzhou. The 50 or so workers at the plant are subject to stringent decontamination procedures—as are all visitors—before being allowed near the sturgeon. The company's employees kill the fish, remove the raw caviar, mix it with a small amount of salt and seal it in 1.8-kilogram airtight containers. The process takes no longer than 15 minutes.

But what about the taste? I have tried the very best farmed caviar from Iran, Spain, Germany, Italy, France and Belgium, but none has the power and intensity of Kaluga Queen's Schrenckii caviar, a hybrid of the Amur and kaluga species. I'm not the only admirer. Alain Ducasse already uses this variety at his eponymous restaurant in Monaco (the restaurant has three Michelin stars), as do three-star chefs Joël Robuchon and Eric Ripert. Lufthansa also serves it in its first-class cabins.

Last year, Kaluga Queen produced 45 tons of caviar, making it the largest producer of farmed caviar in the world. It exports nearly three-quarters of the delicacy. Kaluga Queen anticipates a maximum production of 60 tons of caviar annually, plus the sale of the sturgeon fish itself, which has a firm texture and is also suitable for smoking. The company manufactures four different varieties of caviar, ranging in price from $1,500 per kilogram to more than double that for the prized beluga. It will be a few more years before the beluga species it is breeding attains the necessary maturity to produce the larger roe associated with this variety.

"In the beginning, people didn't believe that we could produce caviar in China and didn't trust us," says Han Lei, vice general manager of Kaluga Queen. "Last year, we exported 2 tons to Russia, and in a blind tasting of 25 different caviars we were ranked first and second. So people listen to us now."