It's one of those bleak Beijing days when the smog lies so low that the sky looks like a white canvas about to collapse. Liu Bolin actually prefers it that way. The city's horrendous air quality is perfect for outdoor photos, and the artist, standing motionless and covered in paint beside a bus stop, has worked too hard for the sun to ruin his shot.

At 39, Liu is lanky, with mussed hair and heavily lidded eyes that make him appear as if he's just rolled out of bed. In fact, he's been awake for hours preparing for the latest addition to his Hiding in the City series that has helped turn him into one of the most recognizable Chinese contemporary artists. Which is ironic, considering the series has earned him the moniker "invisible man."

In 2005, Liu, then a struggling artist from Shandong Province with little to his name but a sculpture degree from China's premier arts academy, watched helplessly as police officers demolished the artist village where he lived and worked. That trauma was the necessity that birthed his greatest invention: a photograph of Liu standing in front of his destroyed studio, his clothes and face painted so that he blends into the broken walls and shattered bricks.

He describes that initial photo and the many that followed as a silent conversation about the conflict between the individual and society, which in China often churns with the forces of economic development. "We are each locked in our own fate," he tells me as assistants dab gray paint on his trousers to match the asphalt behind him.

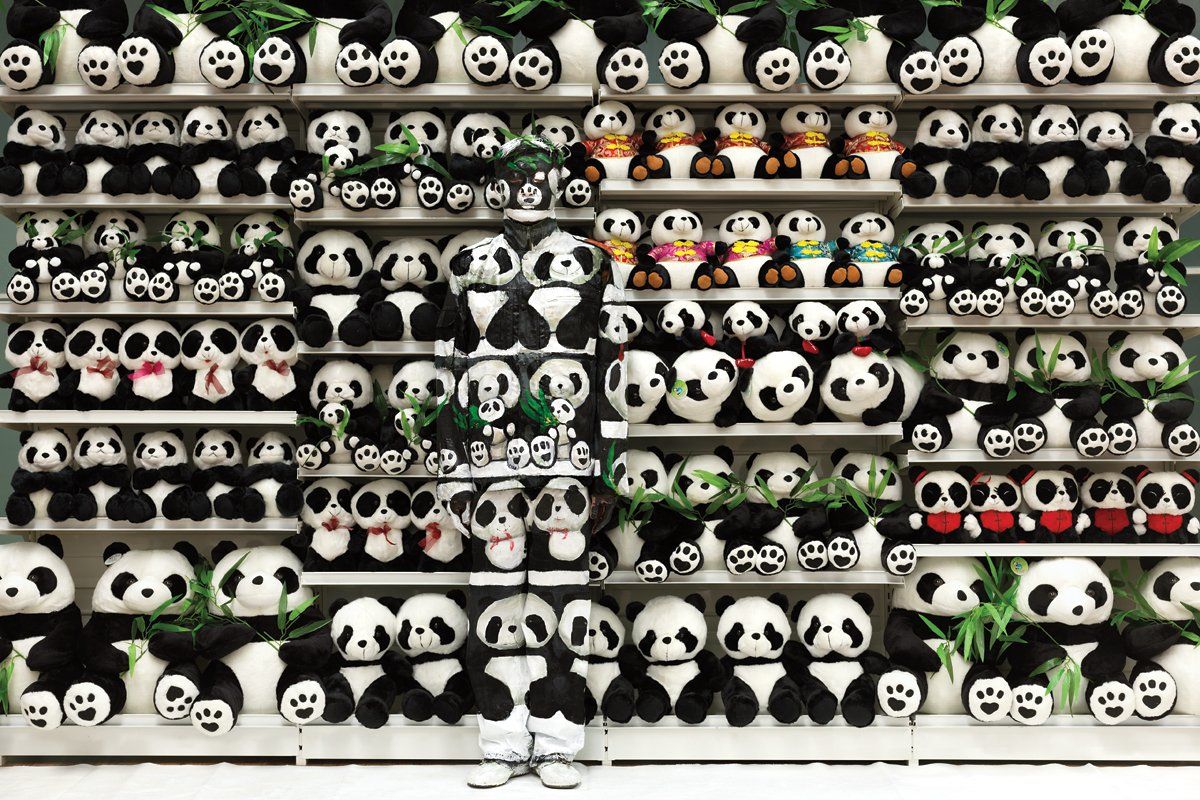

Liu has since been photographed camouflaged into hundreds of scenes across the globe—the vermilion gates of the Forbidden City; supermarket aisles; Olympic propaganda billboards; the lagoons of Venice; Ground Zero; the Wall Street bull.

Often he's impossible to detect at first, but Liu prefers to be ever-so-slightly off kilter. "When I move a bit, it lets people look and think about the art," he says. "I don't want to fade into the larger scene."

Liu's works combine painting, installation, sculpture and photography into a repeated visual pattern so versatile that each image resonates with a different meaning—repression, power, suffering, luxury. It's a gimmick, but one found on museum walls and in private collections. Perhaps more importantly, he's all over the Internet.

A Google search for Liu yields thousands of sites featuring his work. According to Artnet.com, which tracks Web searches of artists' names, Liu is currently No. 29 and recently held the top spot for five months. He is the only Chinese artist in the top 120 aside from Ai Weiwei, No. 54, whose high profile arguably stems more from political activism than his creative expression.

It's a critical distinction. Ai may be a household name, but how many people could identify him by his art? Liu, meanwhile, by nature of his shtick, is immediately identifiable. Eli Klein, the New York–based gallery owner who represents Liu, describes his client this way: "Liu Bolin is the most famous Chinese contemporary artist for his artwork."

To understand how a Chinese artist could, in five years, go from being broke to selling photos for up to tens of thousands of dollars, the answer lies online. Liu came of age artistically just as social media began to dominate popular culture. His work, with its iconic visual repetition and subversive irony, lends itself to the viral physics of Web 2.0—it's art as meme.

Whether that means he's highbrow is up for debate. Philip Tinari, director of the Ullens Center for Contemporary Art in Beijing, likens Liu's appeal to that of "a YouTube video with 3 million views," he says. The work "has a very obvious sort of 'gotcha' people can see and pick out and that makes it interesting. It's like a catchy melody in a pop song."

The world changed for Liu in 2007, when Klein included him in a show at his Soho gallery. When Liu's images drew crowds of serious collectors and the curious alike, Klein instantly knew he'd hit gold. "It was so clear by the reaction from the public that in the West the sky's the limit with Liu's work," Klein tells me. Liu's art has since become a phenomenon, appearing in group and solo exhibitions at museums across the U.S., Europe, and Asia. Collectors are scrambling for a piece of the action. Many of his works, all limited editions, are sold out. Rarity has made their value soar, going for as much as $250,000 for an edition depicting Liu concealed amid a mural of Chinese dragons.

With demand for Liu's photography booming and supply limited, collectors are racing to the secondary market. Even there the waiting list is huge. Two years ago Klein sold one of Liu's most famous images—the artist disappearing into a Manhattan magazine rack—for $18,000. He recently resold it on the secondary market for $46,000.

The production of each piece feels worlds away from the chic art scene where it eventually ends up. Take the bus stop, where Liu is in the process of disappearing into a vibrant propaganda poster decorated with sunflowers. Emblazoned beside the petals are four Chinese words: Patriotism, Innovation, Inclusiveness, Virtue.

These characters are plastered across the city, part of the municipal government's campaign to inspire residents to love their country and improve their character. Few, however, seem to be taking the exhortation to heart. On the poster, someone has scrawled information for what is perhaps a more authentic modern Chinese innovation—fake documents. Need a diploma or a driver's license? Call the number below.

As with many of Liu's works, the act of fading into China's sociopolitical landscape is subtly subversive. By plunking himself into the juxtaposition of two of China's most public industries—propaganda and counterfeiting—he's forcing the viewer to decide which is the real Beijing. Liu is clever enough not to make the explicit contrast, but the sarcasm is palpable.

Over the many hours the image takes to prepare, Liu stands stone-still, descending into a kind of meditative trance as his assistants turn him into a canvas. Passersby, some waiting for the bus, stop and stare; others don't even glance.

At some point, Liu may decide he's had enough of hiding in plain sight. His airy Beijing studio is dominated by sculptures of a peony tree made of phone chargers and another of traditional Chinese clouds—proof that he can do more than what has made him famous. His versatility as an artist defines the harmonious balance of skill and vision so attractive to collectors, says Megan Connolly, director of Chart Contemporary, a Beijing-based art consultancy. "In China, nobody's just a painter," she says, "because here, anything is possible."

Dan Levin is a reporter for Newsweek/The Daily Beast in Beijing. His work has also appeared in The New York Times and Forbes, among other publications.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.