Every day, Rachel Watson—the divorced, alcoholic protagonist of The Girl on the Train, the best-selling 2015 novel by British author Paula Hawkins—commutes to London. Her train pauses for a few minutes at a red signal outside the house of a young couple. She calls them Jess and Jason, and projects her vision of marital bliss onto them: "They're happy, I can tell…. They're what I lost, they're everything I want to be." One day, Rachel sees something unexpected as she gazes out of the carriage window and finds herself involved in the disappearance of the young woman.

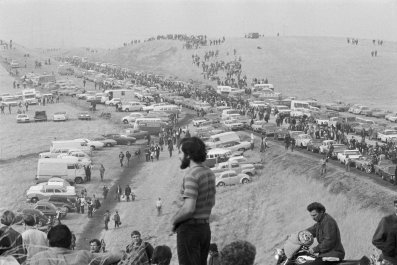

Fans of the book—which has sold more than 11 million copies—might be disappointed to find that the forthcoming movie adaptation has been relocated from England's Home Counties to upstate New York. Rachel no longer takes the 8:04 from the (fictional) Buckinghamshire town of Ashbury to London Euston. Instead, she rides the Metro-North Hudson line past the brick townhouses of Westchester County into New York City.

What would Rachel's journey actually look like? Ashbury does seem to have a real-world equivalent. Described as a "1960s new town, spreading like a tumor over the heart of Buckinghamshire," it sounds like the much-derided Milton Keynes, a town about 50 miles north of London. On a bright September morning, I arrive at Milton Keynes Central station, a low-rise building with gleaming, mirror glass tiles. It's not yet 8 a.m., and the station bustles with people in suits, rushing to catch the train.

Rachel takes a slow train, and so do I: the 7:59 to Euston, where I choose a seat in carriage D, Rachel's preferred spot. Because this is not an express train, there are no businessmen, just a handful of teenagers in school uniform, scribbling their homework, and a young man wearing jogging pants. I can't see any Rachels—no one is sipping guiltily from a can of gin and tonic purchased at the station. Knowing commuter trains, I'm pretty sure that this evening there will be more than a few surreptitious sippers making the journey home from London.

The train arrows south through Buckinghamshire, alongside the green-blue waters of the River Ouzel, past lone horses grazing in fields and the gentle slopes of the Chiltern Hills. The railway embankments are filled with leggy buddleia and the purple spikes of fireweed. In the distance, woods that give the county its gently derogatory nickname—"leafy Bucks"—stretch all the way to the horizon. We slow for the approach to Leighton Buzzard, passing a group of young workers smoking in the parking lot behind a supermarket; in Berkhamsted, we pass the neat back gardens of Victorian terraced houses that abut the train tracks. At Watford, the hills flatten and the woods disappear, replaced by gritty-looking warehouses. By the time we're pulling through northwest London, the trackside houses are more run-down, with broken windows and graffiti. Perhaps it's one of these that "Jess and Jason" live in. But I don't see a woman kissing a man who is not her husband, and at Euston I get off and head for work.

The journey is a commute, no more, no less. That is where, whatever you think of the book, Hawkins works her magic, taking something as mundane as a ride to work and turning it into a thriller that has gripped millions. Will the film pull off the same trick? If it does, next up I'll be traveling the Hudson line.

The Girl on the Train will be released worldwide from October 7.