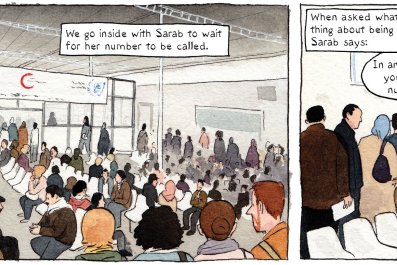

In Berkeley Repertory Theatre's cavernous rehearsal space, in the midst of several dozen actors and tech people, two marching drummers are trying to work out their timing. This is Berkeley, where marching to a different beat is part of the city's historical rhapsody, but these extras are supposed to be leading an invisible procession celebrating the ascent of a major political candidate, the next president of the United States, in fact—an unconventional renegade with little respect for the politesse of traditional campaigning, or the democratic system.

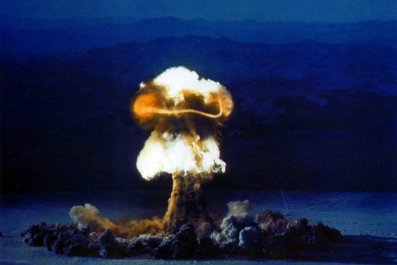

No, not that guy. For this most unconventional of election years, the venerable rep company is presenting an adaptation of Sinclair Lewis's dystopian novel, It Can't Happen Here. Published in 1935, the book was written and revised in just four months by the best-selling author of Main Street and Babbitt, who had watched with alarm the rise of a U.S. senator from Louisiana, Huey P. Long. The former governor known as the Kingfish was an ardent populist, a ruthless demagogue and aspiring presidential candidate who was prepared to outflank FDR on the left—until he was assassinated shortly before the book's publication. Fortunately for Lewis, there were plenty of fascists on the rise in Europe, and it wasn't too hard for readers to squint and imagine a little Hitler in the White House.

Rep Artistic Director Tony Taccone says the group knew it wanted to do something political this fall, but, as Lisa Peterson, the play's director, points out, "There aren't that many American plays written about the electoral process, or set on Election Day, or having to do with politics in America."

It was February. "At the time, Mr. Trump was one of 16 members of the Republican Party seeking the nomination," says Taccone. "He hadn't won anything yet, but he created enough energy that 'it can't happen here' was being quoted in certain editorials, and what he was saying was overt populism."

A lot of the asides doled out by Senator Buzz Windrip (David Kelly), Lewis's dictator in waiting, sound strangely familiar. "Can you believe these so-called journalists?" he asks an imaginary crowd from behind the podium, and when actors playing security guards with clubs take a demonstrator offstage, he shouts, "We're bringing back the good old days!"

Taccone, who adapted the play with Bennett Cohen, swears that only two of Windrip's lines in the play came from Donald Trump. Some ideas just aren't that new, as in the script when the Communist auto mechanic says, "We got 1 percent of the country owning 42 percent of the wealth," and "The system is on the verge of collapse!"

At the heart of the story is Doremus Jessup (Tom Nelis), a newspaper editor from a small town in Vermont. "He was an equable and sympathetic boss," Lewis wrote, "an imaginative news detective; he was, even in this ironbound Republican state, independent in politics; and in his editorials against graft and injustice, though they were not fanatically chronic, he could slash like a dog whip."

"Lewis clearly is Jessup," says Taccone. "He's the voice of the hero." Acerbic and alcoholic, Lewis showed the country a striving, hypocritical side of itself that it couldn't help but recognize. "I know of no other American novel that more accurately presents the real America," the equally dyspeptic H.L. Mencken wrote of Babbitt in 1922. And while It Can't Happen Here seems slapdash now, with characters that are seldom more than cutouts, the book was a critical and commercial success. "What will happen when America has a dictator?" read the copy on the cover of the first edition, and a lot of people couldn't wait to find out.

An Army of Minute Men

It Can't Happen Here was adapted for the theater once before, by the author and John C. Moffitt; that version was produced, in 17 states simultaneously, by the Federal Theatre Project in 1936. "We read that play with a lot of anticipation, a lot of eagerness and thought, This is a really bad play," says Taccone. So they went back to the source.

The version that he and Cohen have fashioned moves along at a gut-churning pace as Jessup and his family witness the changes that come with a Windrip presidency. Those who disagree with him are jailed, the courts are overturned, and the nation (and Jessup's family) soon divided as resistance to the American Caesar and his army of "Minute Men" is fomented. None of the new president's actions should have surprised anyone; before the election, Windrip presents a detailed platform called "The Fifteen Points of Victory for the Forgotten Men" that includes a government takeover of the banks and the unions, and he vows to deny the vote to women, blacks and Jews. On the upside, every family is promised $5,000.

For all the parallels between Windrip's rhetoric and Trump's, there are inherent dangers in doing anything too topical. The comedian Vaughn Meader made a nice living imitating President Kennedy and his family in the early '60s until JFK was assassinated. What if Trump had vamoosed before the November election? "Along the way, we kept saying, 'What happens if he doesn't get the nomination; can we still do the play?'" says Peterson. "We were already committed to doing a play about the American democratic system, the frailty of it even if [Ohio Governor John] Kasich was the nominee."

When Trump clinched the nomination, Taccone announced it at a staff meeting. "Here's the good news," he said: "It could be really good for sales!"

The other danger is that people might be sick of the subject, even tired of contemplating the inherent dangers of a Trump presidency. Taccone isn't worried about his subscribers. "There's an appetite here for history," he says. (One of Berkeley Rep's more popular recent productions was the 2014 musical Party People, about the Black Panthers and the Young Lords in the '60s and '70s.) "A lot of our audience is coming from the assumption that you should be informed about history. I feel extremely lucky. A lot of my colleagues around the country think their audiences don't feel that way—they feel that art is something that is removed from history." Hence the endless retreads of Molière and Chekhov at rep companies across the country.

"When it began to look like Trump was going to lose the election, I found myself thinking, I'm using that [conflicted feeling of relief and disappointment]," says Taccone. "If you look at history, right-wing people fail a lot before they finally take over. Hitler was in jail in 1924 with the Beer Hall Putsch; he spent about a year in jail for his treasonous activities.… He got out, and there were openings because the anger was still there. And the anger's not going away soon, as far as I can tell."

Or as Jessup reflects in the book, "What I've got to keep remembering is that Windrip is only the lightest cork on the whirlpool. He didn't plot all this thing. With all the justified discontent there is against the smart politicians and the Plush Horses of Plutocracy—oh, if it hadn't been one Windrip, it would have been another.… We had it coming, we Respectables.… But that isn't going to make us like it!"