The other day, I came across a quote by Albert Einstein.

Actually, it was a tweet. Actually, it was not something Einstein ever said. Einstein is dead. He died 51 years before Twitter's invention.

But you wouldn't know it from scrolling through the ghostly morass of Twitter.com. Ironically, the blue-check-wielding Twitter account that displays Einstein's name and grizzled visage makes a point of debunking the many quotes misattributed to the late physicist. But it is guilty of its own form of misattribution: verified tweets bearing Einstein's name. There is no known record of the world's most influential theoretical physicist employing the popular hashtag #HumpDay. And when did Einstein ever utter anything as corny as the following tweet?

#ThrowbackThursday to #AlbertEinstein decked out in some serious hat swag. 🎩 pic.twitter.com/EbDnXB546V

— Albert Einstein (@AlbertEinstein) June 25, 2015

If we are going to talk about Twitter's well-established identity problem, then let's also talk about all of the dead celebrities hawking their wares in your feed. Giving a verified Twitter account to a long-dead celebrity is like writing a mediocre novel and then half-heartedly slapping "by Virginia Woolf" on the cover because Woolf's estate gave you permission. It's a waste of everyone's time and a pointless abuse of Twitter's verification tool. Let's ban the dead celebrities from Twitter.

I don't mean parody accounts. Those are fine. Some are clever. Most are not, but that's not the point—they're parodies. They indicate that fact clearly, per company policy, or risk landing in Twitter jail. Sure, thousands of idiots still retweet and follow fake accounts like @BillMurray thinking they're legit, but any observant user can see it's not Murray. That's stated outright in the bio, and even if it weren't, the lack of a verification mark should be an obvious flag.

Verification, for the less obsessed, refers to the bright blue check mark you sometimes see attached to Twitter accounts. (See it there?) That verification badge is one of Twitter's simplest and most elegant features. It doesn't mean the user is necessarily famous or important or even has a lot of followers. While it does often signal a public figure, it simply means the user is who it's purported to be. In other words, the verified mark denotes that Twitter HQ has "verified" that the user is not an imposter—@Cher is really Cher (her tweets are truly inimitable anyway), @POTUS is really the president and so on.

Vote for @VisitGraceland in the @10Best Readers’ Choice for Best Musical Attraction. Thank you very much! http://t.co/dWYo1N9X3h

— Elvis Presley (@ElvisPresley) May 27, 2015

In the case of a politician or less Twitter-savvy celebrity, the verified account might be run by a social media manager or campaign staff, but the relevant idea is that the figure in question approves the account and is not being misrepresented. The trouble with accounts like those of Albert Einstein, Elvis Presley, Marilyn Monroe or Bob Marley—let's call this "Ghost Twitter"—is that those celebrities can't possibly approve the accounts that are in their names. They're dead. And it's not in their will; they've been dead since long before Twitter's existence. Unless Twitter can demonstrate that Elvis is tweeting from heaven, the whole charade defeats the purpose of verification.

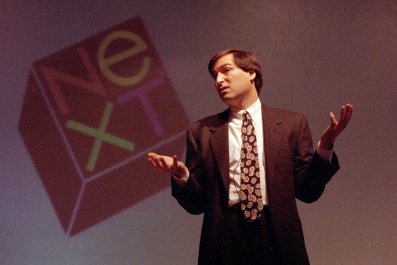

At best, a Ghost Twitter account is run by the late figure's estate and spits out harmlessly corny photos, quotes and endless hashtags. At worst, the account is outsourced to an outside digital content producer (the Einstein Twitter is run by "brand integration" manager Corbis Entertainment) and used to shill products tangentially related to the celebrity in question. Ghost Twitter is a place where Elvis Presley can sell you an App, John Lennon can hawk a $180 boxed set and Humphrey Bogart might give you Father's Day gift suggestions. The tweets read like faceless ad copy, bearing little of the personality that helped make the celebrity famous in the first place.

Don't miss our $4.99 two-day shipping special in the #JimiHendrix online store http://t.co/P16eRCkrYF #GiftCertificates also available too

— Jimi Hendrix (@JimiHendrix) December 19, 2014

Other popular members of Ghost Twitter, as mentioned in a 2012 Forbes.com round-up, include Aaliyah (who mostly just retweets fans), George Harrison (who likes to manually retweet Ringo—eerie!) and 2Pac. The rapper, to be fair, is listed as "2Pac.com," which is a nice way to separate the online entity from the deceased artist. Would these other accounts seem less ghastly if they affixed estate or .com to their display name? Probably. But they might draw fewer followers. George Harrison has around 200,000, while Bob Marley tops a million. Marley's likes to share revolutionary quotes and photos of the reggae star, while also advertising a coffee line that debuted 26 years after his death. There's already occasional confusion about whether Marley is alive, and these accounts are bound to baffle young fans who won't know otherwise.

When is it OK for a dead person to tweet? Roger Ebert's account makes for an interesting case study. The beloved film critic died in 2013, but since he was a prolific tweeter, he gave his wife, Chaz Ebert, keys and instructions for carrying on his online community after his death. At present, there are companies and estate laws in several states designed to help people manage their digital afterlives; Facebook now lets users designate a "legacy contact." Seeing tweets from Roger Ebert in 2015 can be surreal, but they're managed by his widow and cognizant of the writer's wishes, as Chaz Ebert explained to a confused follower recently:

@RStrickson @ChazEbert : No worries, Roger gave me strick orders not to cancel his Twitter account.

— Roger Ebert (@ebertchicago) August 10, 2015

And in 2015, savvy users can take matters into their own still-living hands. Social media apps like TweetDeck let users schedule tweets years into the future. "When I'm on my deathbed, I'm gonna sit and schedule tweets for years to come, tweeting about what it's like after death," freelance writer Ash K. Casson tweeted on June 25. Joe Veix, a writer for Death and Taxes, went further, scheduling eerie messages to be sent out in the year 2086.

scheduled tweets from ~beyond the grave~ pic.twitter.com/LdhBIKsrlY

— joe veix (@joeveix) February 26, 2015

Veix scheduled the tweets using Hootsuite. His motives were surprisingly conceptual. "I was hoping that if I scheduled a tweet late enough, I could be responsible for the world's final tweet," he says. "Also, I was thinking about the fickle nature of the Web. That it'd be fun to mess with a different scale of time to point out this impermanence—scheduling a tweet using an app that will probably vaporize in a year, that's built for a service made by a company that will probably go out of business in five years, that utilizes an infrastructure that will probably collapse in [about] 30 years because of global warming (naïve, unscientific estimate), made for people who will (optimistically) all be dead in [about] 70 years."

Or maybe Twitter will survive. Maybe by 2086 we'll all be tweeting from the afterlife, using death-defying mobile apparatuses that we can't yet imagine. There will be specific social media guidelines that we'll receive in the Handbook for the Recently Deceased, like in Beetlejuice.

For now? Twitter is for the living.