🎙️ Voice is AI-generated. Inconsistencies may occur.

On the 2011 season premiere of No Reservations, Anthony Bourdain trekked to the Western hemisphere's living monument to Marxism, Cuba. There, the peripatetic host slaked his thirst with rum and sated his appetite for culture by taking in a game of baseball, which is truly that country's national pastime. Bourdain seemed charmed by the setting of the Serie Nacional (National Series), the highest level of beisbol on the Caribbean island—until he discovered that alcohol was not served at the concession stand.

"No beer?" he said to his guide, an American named Peter Bjarkman, with a look of pure anguish. "The revolution is clearly a failure."

A strong argument in his favor was playing out (and playing) in the background as he issued that complaint. Rusney Castillo, an outfielder with Ciego de Avila, who was then earning at most a few thousand dollars per month as a baseball player, was rounding the bases after slugging a home run. Three years later, Castillo, following his defection to the Dominican Republic that involved a 23-hour nautical odyssey, would sign a seven-year, $72 million contract with the Boston Red Sox.

Viva la revolucion!

"It used to be, if you played baseball for the Cuban national team, you were the biggest hero on the island," says Bjarkman, 73, a recovering academic who is arguably the most ardent and knowledgeable fan of Cuban baseball residing north of Havana. "Now, all anyone on the island is talking about is what [Los Angeles Dodgers outfielder] Yasiel Puig did last night or did Castillo really get that much money."

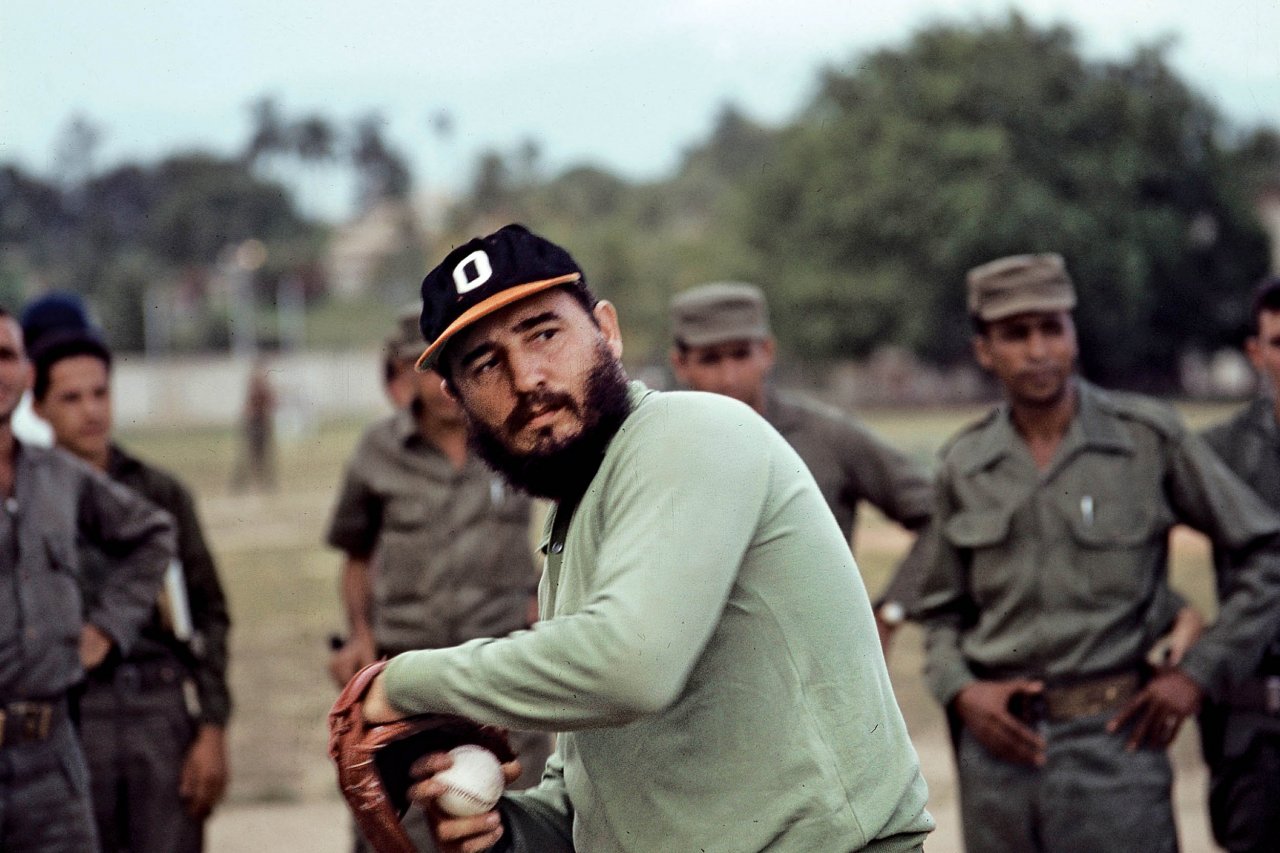

The Cuban Invasion is at last taking place, on a limited basis (and on bases). The soldiers are not clad in drab olive fatigues but rather in Dodger blue and Cincinnati red. The weapons are not missiles, but long balls and 100 mph fastballs. And due to the trade embargo between the United States and Cuba that dates back to 1962, the soldiers leading this invasion are contraband.

Major League Baseball (MLB) doesn't allow teams to sign Cuban players. Directly. MLB skirts this self-imposed ban by having the Cubans establish residency in another sovereign land first. Today, mas Cubanos populate big league rosters than at any time since 1967, while signing contracts that conjure a Bay of Capitalist Pigs.

In addition to Castillo, there's outfielder Yoenis Cespedes of the Detroit Tigers, who signed for four years and $36 million. First baseman Jose Abreu, Chicago White Sox, gets six years, $58 million (plus a $10 million signing bonus). Outfielder Yasmany Tomas, Arizona Diamondbacks, gets six years, $68.5 million. The most celebrated Cuban in The Show is Puig (a seven-year, $42 million deal), and he is not even the highest-paid Cuban in the Dodgers' clubhouse. That distinction belongs to shortstop Alex Guerrero, who is earning $7 million as a rookie this season.

Recall that all of these deals were signed before the players had taken a single at-bat in the United States, but after they had fled their country illegally, i.e., defected. In doing so they risked imprisonment and death while sometimes placing their fates in the hands—and boats—of the same unsavory characters who smuggle drugs and weapons. "When El Duque [Orlando Hernandez] first signed to pitch with the New York Yankees in the mid-1990s," says Bjarkman, "he was asked if he'd ever been in a high-pressure environment like facing the Red Sox. He just laughed."

And remember that most of these players formerly competed against one another in a league in which the median salary is $125 per month, and the price of admission for a game is approximately 12 cents. Where every night, when you consider the age and dilapidated condition of the ballparks and fields, is Retro Night.

"You go to the ballpark in Havana, Latin American Stadium," says Bjarkman, "and pieces of the roof have been coming off for years. Most of the ballparks were built in the '60s."

The Cuban Invasion is proving to be far more successful than the CIA's inept attempt to invade Cuba in 1961. Abreu, of the White Sox, was named American League Rookie of the Year. Four seasons ago, closer Aroldis Chapman of the Cincinnati Reds threw the fastest pitch (105 mph) recorded in major league history. Five Cubans made an MLB All-Star roster last July.

That number is even more impressive when you recall that every Cuban in the MLB had to take a circuitous route to get to the U.S., so the footprint is relatively light. Consider that the Dominican Republic, a Caribbean island nation with 2 million fewer citizens than Cuba's 11 million, has more than four times as many players (83) on major league rosters this season.

"Every single major league team has a baseball academy in the Dominican Republic where they develop talent," says Bjarkman, who has just written his third book on baseball in the Caribbean, Cuba's Baseball Defectors: The Inside Story. "From my perspective, though, while it has been good for those individuals who make it to the big leagues, it has been bad for the Dominican Republic. It has gutted their system."

In 1959, the Marxist revolution led by Fidel Castro led to the overthrow of the government. That same year, the Triple-A Havana Sugar Kings, an affiliate of the Cincinnati Reds, won the equivalent of the minor league World Series. The following year El Jefe nationalized all U.S. business interests in Cuba and the Sugar Kings relocated to Jersey City. In 1961 Cuba's Communist government issued National Decree Number 936, which placed a total ban on professional sports.

Baseball did not perish in Cuba, but professionalism did.

At the Serie Nacional level, each of Cuba's 14 provinces (plus one island and the city of Havana) would compose a team of truly representative players. If you were raised in Cienfuegos, you played for Cienfuegos. Players were showered not with vast sums of money but with community and sometimes national adulation. The best players went on to represent the Cuban national team, a juggernaut that at one point went 156 consecutive games without a defeat.

"The closest thing I can compare to baseball in Cuba is high school football [in the U.S.]," says Bjarkman. "The community supports the team, and the fans know the players. They've known them their entire lives. It's baseball for baseball's sake, not baseball as part of a shopping mall the way we have here at major league ballparks."

Those aforementioned shopping malls are quite lucrative, and in the past six years, beginning with Chapman's defection at a tournament in the Netherlands in 2009, the shopping mall owners have been ravenously plumbing for Cuban talent. Cost is no issue. Major league rules stipulate that all prospects from the United States, Canada or Puerto Rico are subject to the annual MLB Draft. Prospects from outside countries are not, though, and they can sign as free agents. And even though MLB recently imposed rules in which a team that exceeds its pool of allotted money for signing such a player will pay a 100 percent tax, the measure has failed to deter suitors. "The Red Sox just signed a 19-year-old shortstop named Yoan Moncada for $31.5 million," says Barkman. "On top of his salary, they must pay $31.5 million in 'taxes' to MLB."

It's an absurd economic structure. Mike Trout of Millville, New Jersey, earned just above $2 million in his first three seasons despite being named American League rookie of the year, American League MVP and making three All-Star teams. Moncada was handed an $8.27 million signing bonus on the day he signed.

Speaking of absurd economic structures, have you visited Cuba? Most of the populace is languishing, and its primary source of distraction, baseball, is being strip-mined by MLB while the government receives nothing in return. But must it always be so?

In the past two years Cuba has loaned out four veteran (read: loyal) national team members to play overseas in Japan's famed Nippon League. The players, such as 30-year-old infielder Yulieski Gourriel, earn low-seven-figure salaries while kicking back 20 percent of it to the Cuban government...which is still less than Uncle Sam will garnish from Trout's income. As part of the bargain, the players must return to play in Serie Nacional, which runs from October to April. "That money helps with [Cuba's] baseball infrastructure, which sorely needs it," says Bjarkman, who has smuggled Louisville Sluggers to Cuban sluggers. "But that would never work with the United States because major league teams would never allow their players to play 90-game schedules in Serie Nacional."

Last December 17, President Barack Obama tossed a curveball at foreign diplomacy. "Good afternoon," said the commander in chief. "Today, the United States of America is changing its relationship with the people of Cuba." Obama's announcement that the U.S. would seek to reopen diplomatic relations with Cuba after a 54-year abeyance was interpreted by some as an invitation for Cuba and Major League Baseball to "play ball!"

But it wasn't, at least not for the foreseeable future. "Nothing has changed," says Bjarkman, who has a Ph.D. in Cuban Spanish linguistics. "Most of those reporting or dreaming about [unfettered access to Cuban talent] simply have not done their homework."

The same day as President Obama's announcement, Major League Baseball issued a directive to its 30 franchises reminding them that it was still illegal to scout players in Cuba, or to sign them directly. Cuba and the MLB are not business partners, and there's no indication that they soon will be. "The minute Cuba was to open up its talent base to Major League Baseball, MLB would want to set up academies there and develop talent themselves," Bjarkman says. "Baseball in Cuba would effectively be owned and operated by U.S. corporations and that's contrary to everything that the Fidelistas who are still in power are about."

So, regardless of how badly Cuba needs the money—how much prettier would those ballparks be with an infusion of 20 percent of Rusney Castillo's $72 million?—the government remains unwilling to abandon its principles (a foreign concept, to be sure). Meanwhile, because no contracts exist between the countries, there is no such thing as breach of contract. And that is why, one night a week, one of Cuba's state-run television stations airs, on tape-delay, a Major League Baseball game ("without the expressed written consent of Major League Baseball").

"The funny thing about that," says Bjarkman, "is that they always take care to air a game in which neither team has a Cuban ballplayer."

Such games are becoming more difficult to find.