Rachel Law, the 20-something co-founder of a New York startup called Kip, is sitting next to me at a café, tapping her phone screen to show how the company's service based on artificial intelligence allows users to shop while on Slack by communicating not in typed or spoken words but in cartoonish emoji. (Image of cheese plus image of windmill equals...an order for a cheese Danish.)

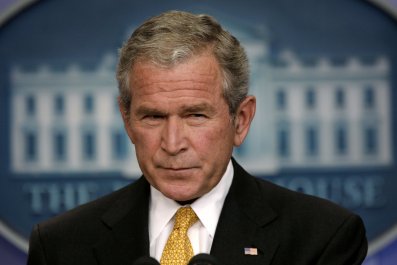

If Law were doing this demo for either Donald Trump or Hillary Clinton and used the terms artificial intelligence, Slack and emoji in the same sentence, each candidate's brain would no doubt seize up like an engine that had run out of oil.

We have a problem, folks. Over the next four-year presidential term, a swarm of fantastic new technologies, such as artificial intelligence, virtual reality, blockchain, personal genomics and drones, will profoundly alter society, business and geopolitics in ways we've never seen. And our two major-party presidential candidates don't have a clue.

This November, we're going to elect a president who is promising to solve 20th-century problems but can't see potential 21st-century solutions—or nightmares. Clinton published her comprehensive tech plan this summer, titled "Initiative on Technology & Innovation." It plods through a lot of familiar policy-wonk stuff: net neutrality, internet governance, cybersecurity, online privacy, improving the patent system. All are important topics, and they could've been on Barack Obama's to-do list in 2008 or Al Gore's in 2000.

Astoundingly, the document does not contain the term artificial intelligence—even though AI will likely turn out to have a bigger impact than any technology since the transistor. The document twice mentions machine learning—a subset of AI—in passing, without context. The words drone or genomics don't appear at all. Neither does emoji, in case you were wondering. Clinton's views are as unexciting as a matzo ball.

It's not just the platform that's missing the future—it seems to be Clinton herself. A disturbing part of the latest FBI report on her email troubles is the details about her complete lack of tech savvy. She comes off like a favorite aunt who sticks to her flip phone and buys music on CDs.

And Clinton makes Trump look like a tech Neanderthal. No doubt the GOP nominee would think the term autonomous vehicle means a limo with a driver. Trump has not released any sort of tech policy. The Information Technology and Innovation Foundation just published a nonpartisan report comparing Clinton's and Trump's positions on just about every tech topic. It was a challenge to write because, as the report says, "the most distinguishing feature of the Trump campaign agenda in this area has been its notable lack of articulated policy positions."

In other words, Trump doesn't have anything to say about the old, wonky tech issues, much less the coming issues that are going to grip the next president. This is the guy who said he'll fight terrorist recruiting by shutting down "parts of the internet," the way you might close a road by putting up some orange cones. No wonder 145 tech leaders signed a letter declaring that "Trump would be a disaster for innovation."

So what are some of the hard issues chugging toward us?

We need to start thinking through AI policy now, before the technology gets away from us. AI needs ethics. Stanford University just put out a study, "Artificial Intelligence and Life in 2030," raising several important ethical questions. "Who is responsible when a self-driven car crashes or an intelligent medical device fails?" Or "How can AI applications be prevented from unlawful discrimination?"

AI threatens to automate away vast numbers of jobs. Some leaders from Silicon Valley are proposing that the government institute a guaranteed basic income—a safety net for everyone. Is that the right approach? Trump has his followers whipped up about immigrants and trade taking their jobs. AI promises to make that seem like swatting mosquitoes when a self-driving semitruck is about to hit you.

Google, Facebook, Microsoft, IBM, Amazon and other companies are racing to build AI technology because they know AI is likely to be dominated by a couple of superpower near-monopolies. AI gets better the more it's used. So whoever establishes a lead can start to run away from competitors—more use begets better AI, which lures more users until one or two winners take all. But do we want that? We didn't want John D. Rockefeller to control all the oil in the 1910s, so the government broke up his Standard Oil monopoly. Ceding control of all the AI to one or two powers will be even more dangerous.

I recently visited Philip Rosedale, a virtual reality pioneer, at his company, High Fidelity. He's convinced that in a decade, we'll have a global virtual reality internet—almost a parallel world to our own, buzzing with commerce, entertainment, parties. Some people will have jobs inside VR, but who will run that world? Rosedale? Mark Zuckerberg, whose Facebook bought VR company Oculus Rift? And does a private company get to make the laws there? It would be nice if our nation's leader had some thoughts on this.

Digital currencies like bitcoin and startups like Stripe and Digit are reimagining the world's financial and banking systems. Drones are on the verge of filling our skies. While we're arguing about Obamacare, personalized medicine driven by AI, the Internet of Things devices and cheap genome sequencing will soon deeply know each individual, rendering obsolete old-style insurance based on large pools of customers. How about we shape finance, airways and health care so they embrace those new realities?

The point is, we badly need a tech-wise president. And we're not going to get one.

Sitting with Kip's Rachel Law and thinking about our presidential choices, I realized that one of the barriers to thoughtful tech policy from Trump or Clinton might simply be their age. Trump was born in 1946, Clinton in 1947. When PCs took hold in the mid-1980s, both candidates were approaching 40. In the late 1990s, as the dot-com boom ushered in the internet, they were 50. When the iPhone came out in 2007, they were 60.

Trump and Clinton are from the TV generation. The iPhone generation thinks in a completely different way. "The generations are more different from each other now than at any time in living memory," writes Paul Taylor of the Pew Research Center, citing reams of data, in The Next America: Boomers, Millennials, and the Looming Generational Showdown.

AI, emojis, bitcoin, VR—it's unlikely Trump or Clinton will ever grok any of it. So here's to hoping that between now and the next election a technology leader emerges to run for president—the iPhone generation's JFK.

Just not Peter Thiel, OK?