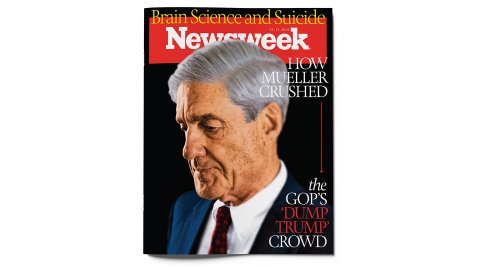

"Complete and total exoneration."

Donald Trump's words echoed across Washington on a Sunday afternoon in late March as Attorney General William Barr revealed the long-awaited conclusions of the Russia-gate probe. Indeed, after nearly two years of investigation into Kremlin interference in the 2016 campaign, special counsel Robert Mueller had found no collusion. And while, according to Barr, Mueller carefully noted that his report did not completely exonerate Trump on the charge of obstruction of justice, the president blew through the legalese, knowing the distinction would make no difference to much of the American public and certainly not to his loyal Republican base.

"It's a shame that our country had to go through this," he said before boarding Air Force One for the nation's capital after a weekend of golf at his Mar-a-Lago resort. "To be honest, it's a shame your president had to go through this."

He added, "This was an illegal takedown that failed."

Republicans celebrated. Democrats griped. Presidential contenders, a New York Times headline blared, would now have to emphasize—gulp—issues. But it was yet another group that felt the sting almost as much: the Never Trumpers.

For much of the past two years, this constellation of Republican lawmakers, conservative pundits and policy wonks, and GOP operatives had hoped Mueller would help rid them of, as they saw him, the crude political rube who had hijacked their beloved Grand Old Party. Some campaigned loudly for Trump's demise, on Twitter and cable news. Others, however, operated mostly in the shadows. Like dissidents in an authoritarian country, they held secret meetings in a conference room of a little-known Washington think tank called the Niskanen Center. About once a month, they shared private polling data on Trump, passed along the names of political activists around the country who opposed the president and, perhaps most important, discussed potential primary challengers who could lead the "Dump Trump" movement.

Just weeks before the Mueller news, a group of lobbyists, congressional aides and policy experts from conservative think tanks spent an entire session talking about how to sell free trade and fiscal restraint to voters in the age of Trump. Now, these Republicans face a reinvigorated and vengeful standard-bearer, fully embraced by a party establishment no longer encumbered by the looming threat of a criminal indictment from Mueller. "The cloud hanging over President Trump has been removed," said Senate Judiciary Committee Chairman Lindsey Graham.

Publicly, the Never Trumpers say their unlikely cause endures. "This was never about Mueller or the Russia investigation," says Rick Wilson, the Florida-based Republican operative and author of Everything Trump Touches Dies. "It's about his unfitness for office."

"He's incompetent and really bad for the party," says Mike Murphy, the veteran GOP strategist, "and he'll hand the country over to a party that's going full socialist."

"We need to see the Mueller report," conservative commentator Bill Kristol wrote on Twitter, echoing Democrats on Capitol Hill. The evidence "will confirm he ought not be re-elected."

But privately, members of this group acknowledge the dream is dying, if not already dead, with the herculean task of bringing down an incumbent president from inside the party now infinitely harder, if not impossible. Yes, a bevy of other investigations in state and federal prosecutors' offices, as well as in Congress, are proceeding on everything from hush money payments to money laundering to illegal donations, and Mueller's confidential report—Barr has vowed to release a public version in the coming weeks—may yet contain damaging details about Trump's conduct.

But for the moment, it seems the single, largest bullet is gone. After nearly two years of Russia-gate frenzy and impeachment talk, Democratic leaders are moving on, attempting to pivot to health care and other kitchen-table issues. And Trump and the GOP are now the ones on the offensive, with the president pledging to investigate the "treasonous" people behind the Mueller "witch hunt." A Reuters/Ipsos poll found Trump's job approval jumping 4 points, to 43 percent, in the wake of the findings.

Some Never Trumpers asked for anonymity to speak freely post-Mueller, an acknowledgment of the changing political currents and Trump's new lease on life.

"I'm not going to deny that this is a win for Trump, a big win. And it makes our job harder," said one leading Never Trumper. "He'll get a bounce from this. The question is: Will he piss it away by being Trump?"

Dumping Trump has always been a quixotic effort. Throughout his tumultuous presidency, he has remained overwhelmingly popular among registered Republicans. His approval rating among party members is 84 percent, according to a recent Harvard CAPS/Harris poll. GOP critics, like former Arizona Senator Jeff Flake, soon found their own campaigns foundering when they questioned the president, his positions or his appointees. "This is very much the president's party," Flake, who decided not to run for re-election last year, told The Hill. "When you look at the base and look at those who vote in Republican primaries, I think that is clear."

But while much of the rank and file who supported others in the 2016 primaries got over their shock—winning the general election tends to heal a lot of political wounds—a significant minority didn't, haunted by the image of Trump accepting the Republican nomination to the sounds of the Rolling Stones' "You Can't Always Get What You Want."

Unsurprisingly, many of them hail from Bush World—those who helped George W. in 2000 and 2004 and then Jeb in 2016—believers in a mainstream Republicanism that defined the GOP for generations: fiscal conservatism, expansive free trade, muscular foreign policy. They watched from the wings as Trump humiliated "Low Energy Jeb" and ridiculed "compassionate conservatism," paving the way for nativism and nationalism.

"Do we want some payback?" asked Wilson, a strategist for Jeb Bush in 2016. "Sure we do."

Murphy, who ran Bush's 2016 super PAC, chuckles when he hears that. "Yeah," he cracks, "I'm the idiot who blew $100 million on Jeb." The longtime consultant has been a strategic force behind many of the GOP's rising stars for decades. Before running Bush's lavishly funded operation, he was an adviser for John McCain's "Straight Talk Express" bus campaign in 2000, Mitt Romney's campaign for governor of Massachusetts in 2002, Jeb's successful bids for Florida governor and Arnold Schwarzenegger's gubernatorial campaigns in California. His motive, he says, is political.

Trump, Murphy argues, means "political death for the party." Last year's midterm elections, he says, were a referendum on the president. Moderate Republicans, independents and suburban women all fled the GOP in droves, leading to a loss of 40 congressional seats and control of the House. For any number of reasons—Trump's crudeness and his harsh tone on immigration among them—he does not see them coming back in 2020.

Murphy views himself as the chief communicator of "a Paul Revere project," trying to persuade grass-roots activists—some 10,000 to 13,000 nationwide, all in his digital Rolodex from past campaigns—that Trump will drag down the party in 2020. Even post-Mueller he believes Trump is "political anthrax" that would wipe out Republicans up and down the ticket. Whether GOP voters listen is an open question.

In January, a Marist poll found that 44 percent of Republicans want Trump to face a primary challenger. Other surveys have found similar results in New Hampshire and even higher numbers in Iowa.

The task of finding that challenger has largely fallen to Kristol, the neoconservative political analyst who helped recruit Sarah Palin to revive McCain's flagging presidential bid in 2008. He too has objections to Trump's policies—the president's isolationist strain and his disdain for traditional American alliances in particular—but his opposition seems more visceral. He considers Trump a "boorish clown" and believes his alleged sexual dalliances with a porn star and a pinup model are beyond the pale.

Kristol and his deputy at the Defending Democracy Together nonprofit, Sarah Longwell, have tried to entice several GOP politicians, including Flake, former Ohio Governor John Kasich, and current Nebraska Senator Ben Sasse. All have declined. He has had one prominent nibble: Larry Hogan, the popular Republican governor of Maryland who won two terms in a deep blue state. His father, a congressman from Maryland, was famously one of the first GOP politicians to turn against President Richard Nixon during Watergate.

But even Hogan, who has opposed Trump on immigration and fiscal policy, has said publicly that the Mueller report was going to influence his thinking, and he declined comment when Newsweek sought to clarify his position after the special counsel news. He is, however, still planning on attending the Politics & Eggs breakfast organized by the New Hampshire Institute of Politics in April, a tradition for all candidates testing the presidential waters. When I spoke with him in March, he was clear-eyed about the prospects. His biggest worry?

"1884," he said, in reference to the last time a sitting president was denied his party's nomination.

For now, the only Republican actually leaning toward running against Trump in 2020 is William Weld, the 73-year-old former Massachusetts governor who ran for vice president on the Libertarian ticket in 2016. But Kristol and others worry that anyone who opposes a reality-TV sensation like Trump needs to be a star in his or her own right—that is, someone who is already nationally recognized and could plausibly be president.

Mitt Romney, the 2012 Republican presidential nominee, sparked interest in January, when, as a new senator from Utah, he penned an op-ed in The Washington Post trashing Trump. "With the nation so divided, resentful and angry, presidential leadership in qualities of character is indispensable," he wrote, adding, "I will speak out against significant statements or actions that are divisive, racist, sexist, anti-immigrant, dishonest or destructive to democratic institutions."

Romney tells Newsweek that he'll also praise Trump when it's warranted—"and on the economy and on judges, he's done well"—but criticize the president when he fails to live up to the stature of the office. "It may be an old-fashioned notion, but the president is a role model for some people, even in 2019, and I think [Trump] has to keep that in mind." Did that mean he was considering a primary challenge next year?

"I'm here to be a senator from Utah," Romney says.

With little more than polite talk about "qualities of character," Trump and his re-election campaign should be breathing easy, right? Not exactly.

When Weld announced an exploratory committee in February, the president's political high command wasted no time trashing him. Corey Lewandowski, who helped run the Trump campaign in 2016, called him "a pathetic opportunist" who "just wants to stay relevant." Steve Stepanek, a Trump ally who heads the New Hampshire GOP, said Weld "isn't a Republican, and we don't want him back."

The reason for the vitriol against even an obscure former governor was simple: When an incumbent is challenged in his own party, it weakens his chances. Ronald Reagan ran against Gerald Ford in 1976; former Senator Edward Kennedy tried to unseat Jimmy Carter in 1980; and Pat Buchanan led a populist uprising against George H.W. Bush in 1992. All three presidents survived those challenges but lost their general elections. That's why one senior Trump political adviser acknowledges, "Obviously, we don't want any part of [a primary challenge]. We'd be much better off spending our time and money defining all these lunatic left-wingers running for the Democrats."

What would a primary challenge look like? For starters, any candidate who goes for it has to assume he or she will lose, Murphy says. "If you're liberated, you're truly dangerous," he notes. And the case against Trump? His presidency is one of "uncivil, loud incompetence." He and others cite as examples the recent government shutdown; Trump's "obsession," as Wilson puts it, with the border wall; and his affinity for trade wars. Longwell, Kristol's deputy at Defending Democracy Together, says, "I want there to be a viable, responsible Republican governing party," and she bets a lot of other GOPers across the country agree with her.

It is difficult to overstate the contempt with which Trump's campaign operatives, and most of his supporters, view this assessment. "It's hard to know what planet these people are on," says Lewandowski. Team Trump rejects every single aspect of the Dump Trump critique.

They start with a fundamental point: The people fantasizing about ousting Trump seem to be operating from the premise that a conventional Republican presidential campaign can be successful: tax cuts, deregulation, smaller government, free trade and more legal immigration at home, American strength and leadership abroad. "That's McCain in 2008, Romney in 2012. The last candidate to win as a standard Republican was George W. Bush, and that was a long time ago," says a key Trump political operative. "These people seem to think that he's this political accident and that once he's gone the GOP can just go back to what it was and somehow actually win a presidential election."

This source says, "That is the very definition of insanity."

Trump supporters argue that the politics of three issues in particular—trade, immigration and America's role in the world—have been irrevocably changed by his election. They believe the surest way for the GOP to lose the three key states that gave Trump the presidency in 2016—Pennsylvania, Michigan and Wisconsin—is to run a "free trade is great" campaign. In the battleground Midwest, "no one believes that," says Lewandowski, "and you can sure as hell bet the slouching toward socialism Democrats are not going to run to the right of Trump on trade next year."

Trump's advisers insist that a hard line on immigration keeps his base solidified. And even though a dozen Republican senators revolted and voted against emergency funding for the border wall in March, Trump's political advisers believe the issue has quiet resonance outside Washington, among Americans who don't "sit around and get lectured about how they're racists on CNN and MSNBC every night," as one White House aide puts it. In this calculus, the GOP might attract moderate suburban women in northern Virginia or Main Line Philadelphia by toning down the rhetoric about illegal immigrants, but they'll say goodbye to Mahoning County, Ohio, or Macomb County, Michigan.

On key foreign policy issues, where many mainstream Republicans in Congress are uneasy with Trump's desire to pull U.S. troops out of Syria and Afghanistan, his political advisers say all the president has done is ask common sense questions: What are we doing in Syria if ISIS is gone? Why, after 18 years, are we still in Afghanistan? And shouldn't our NATO allies pay at least a little more toward their defense? Is that really so outrageous to ask? "The fact that the foreign policy establishment, both Democrats and Republicans, gets so upset when Trump talks about this stuff is simply a reflection of how ossified they are," says a Trump adviser.

Moreover, the president's backers point to the numbers, in particular in Iowa and New Hampshire.

Sure, some Republicans say they'd like to see someone challenge Trump, but the most recent poll by The New Hampshire Journal, taken in the midst of the government shutdown, showed that 80 percent of GOP respondents approved of Trump's performance in office. Only 10 percent disapproved. In Iowa, the numbers are similar. And now, Team Trump argues, the end of the Mueller "witch hunt," as Trump repeatedly called it, "will boost our numbers everywhere," says Lewandowski. "Bank on it."

Trump's supporters like the fact that on taxes, gun rights and the judiciary, he has governed very much as a conservative, "one of the most conservative presidents in a generation," argues New Hampshire GOP campaign consultant Greg Mueller. The economy is strong, the stock market's up, "what's not to like?" GOPers in New Hampshire are willing to set aside the "stylistic and character critique of the president and support him again. They like him."

Some conservative operatives and analysts believe the Dump Trumpers are making a big strategic mistake in even thinking about trying to run a conventional, Romney-like candidate. Conservative columnist Philip Klein wrote recently what a lot of conventional Republicans in the House and Senate worry about: "If somebody runs…on a traditional free market and free trade platform and gets slaughtered by Trump, it only bolsters the strength of the populist movement within the party and makes the traditional conservatives look even more irrelevant." Further, he notes, a primary challenge that weakens Trump and ends up in his defeat in the general election will only further inflame distrust among the grass roots toward elites. "I'm not sure we want to go down that road," says one GOP congressman.

So will a challenge ever materialize? Much depends on Trump.

His seat-of-the-pants governing style still nauseates a fair number of Republicans in Congress, some of whom counseled him to use the post-Mueller moment to move on and push big-ticket items on his policy agenda, as other scandal-plagued presidents have done. But so far, Trump has given them little indication that he would change his bombastic ways.

"There are a lot of people out there that have done some very, very evil things, some bad things, I would say some treasonous things against our country," the president told reporters during an Oval Office meeting a day after the Mueller report reveal. "And hopefully people that have done such harm to our country—we've gone through a period of really bad things happening—those people will certainly be looked at."

Later, he redoubled his attacks on the media as the "Enemy of the People and the Real Opposition Party" as his press secretary tweeted out a New York Post graphic dubbed "Mueller Madness," a basketball-style bracket of "angry and hysterical" Trump "haters," including Kristol.

Those who know Trump best say to expect more of the same. "If you think Donald Trump will just let this whole thing go without capitalizing on it politically, then you don't know Donald Trump very well," former campaign and White House adviser Steve Bannon tells Newsweek. Says another longtime friend, "Donald Trump fights back, and he goes after his enemies. Always has, always will."

But even as pundits began debating the dark overtones of political retribution and the risk of overreach, Trump shocked the system again. His Justice Department backed an appeal to entirely invalidate Obamacare in a federal district court in New Orleans. Surprising both parties, Trump then declared, "The Republican Party will soon become the party of health care."

The Democratic leadership, which used health care as an issue to great effect in the 2018 midterm elections, immediately pounced. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi introduced legislation that would enhance the Affordable Care Act, and several Democratic presidential candidates denounced the administration's court filing. "We will not let the Trump administration rip health care away from millions of Americans," Massachusetts Senator Elizabeth Warren tweeted. "Not now. Not ever."

This seemed to be the kind of unforced political error that the Never Trumpers say defines Trump's presidency and will doom the GOP's chances in 2020. If that turns out to be the case, they will at least be able to say this: We warned you.