One bustling afternoon in Kenya's capital, Nairobi, three gay men from Uganda were walking home from a sexual health center when they were stopped by a police officer. Nelson, 25, was carrying a purse. In it, the police officer discovered pamphlets about gay rights, as well as condoms and lubricants that he'd received just moments earlier at the center.

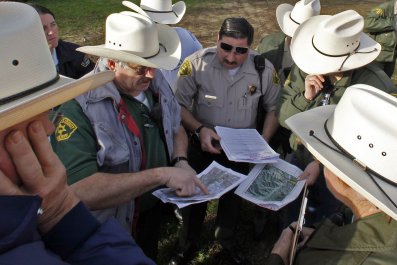

To the officer, "that was the evidence that we were gay and we had come to destroy Kenya with our habits," Nelson recalls. (The names of all refugees in this story have been changed for their protection.) He says police took the three of them to jail, placing them in a cell with straight prisoners and announcing that "these are gay people—you don't know what they will do."

The inmates immediately began questioning, then slapping, the gay Ugandans. This continued until Nelson managed to persuade them that the police officer was lying in an attempt to blackmail them into offering a bribe—a common practice in Kenya. The three gay Ugandans spent the night in that cell, until representatives from the sexual health clinic arrived in the morning and persuaded the police to let them go. Upon leaving the jail, Nelson says one officer threatened him: "We know where you stay."

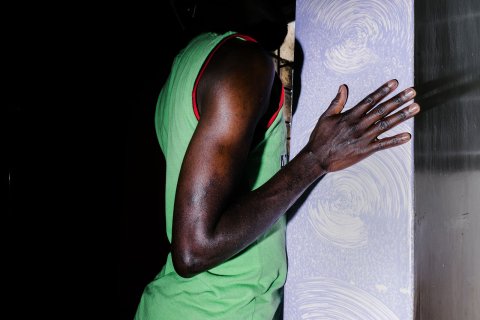

He probably did. For months, nearly two dozen gay, lesbian and transgender Ugandans had been living in a large house on the outskirts of Nairobi in an area called Rongai. Long after a court struck down Uganda's infamous anti-gay law—dubbed the "Kill the Gays" bill for a death penalty provision in an early draft—LGBT people in Uganda were still being disowned by their families, hunted down by neighbors, jailed by police, even killed. Hundreds fled Uganda—mostly to Kenya, where they are faring little better.

Kato, 28, says life used to be better in Uganda. "Kampala is the center of fun in East Africa," he says, speaking of his hometown. "We had out places. Places that were gay-friendly." He says the owner of one popular club would regularly pay off the police so they wouldn't raid the place.

But in Nairobi, the refugees don't go clubbing. Instead, they cobbled together enough money to buy a DVD player and a small TV. "It's better than going out to dance and getting arrested," Kato says. On the floor near the door of the apartment rests a tall stack of ripped DVDs and CDs with songs and music videos by popular Ugandan recording artists. "The music reminds you of home," he says.

But home changed for him when his family discovered his secret. One day, a woman was flipping through the phone of Kato's boyfriend when she discovered nude photos of the couple. The woman was friends with Kato's sister, so she recognized him. She forwarded the images to her.

"It was a Friday," Kato recalls of the night he was outed to his family against his will. "We were out. My sister called me. I stepped outside. She just shot straight to the point—she just asked me if I'm gay. Before I could respond, the phone cut off. I tried calling her back, but she didn't answer."

She hasn't spoken with him since. The only member of Kato's family who has was his younger brother, who warned Kato that the family was planning some sort of intervention for him. Kato stopped showing up for work at the computer shop where he was employed, out of fear that they might find him there. He persuaded his kid brother to snag his passport from the house and bring it to him. With that in hand, he left for Kenya.

I ask Kato if he ever thinks of returning to Uganda. He says he's afraid that his family or the police would hold him there against his will. Besides, here in Kenya he's focused on his future—resettling in America or Europe—not on his past. "When family turns their back on you, it's like a whole chapter has been closed."

The LGBT refugees living in Nairobi are just 500 or so among the nearly 600,000 refugees in Kenya. Last year, LGBT refugees in Nairobi received a disproportionately large number of slots allocated for resettlement of refugees, but it was still only 75. Those who remain wait to see if they'll be among the lucky few.

Two dozen of them used to live at the Rongai house, a sort of safe haven for Kenya's LGBT refugees. There, they spent their days cooking and cleaning, talking, texting and waiting for a call from some foreign embassy offering them a one-way ticket to a new life.

On several occasions, residents say, police came to the Rongai house threatening to deport all of them. Authorities were not their only worry. One evening last year, a transgender refugee and two gay men were walking to buy food when they were attacked by women in the neighborhood, who accused the gay refugees of "stealing our men."

One afternoon last December, a Kenyan man came to the gate of the Rongai house with a warning: Neighbors were plotting to attack the gay refugees that night and run them out of town. The refugees didn't wait. They fled, scattering to different apartments across the city.

Many of these refugees grew up in urban, middle-class families and loathe living in a hot, squalid refugee camp, as Kenyan law requires of all refugees. They are city people, accustomed to partying at secret gay clubs in Kampala. Nairobi too is a cosmopolitan city. One Ugandan refugee spoke fondly of dancing at many of the clubs that dot "Electric Avenue" in the city's Westlands district.

In Nairobi, young Kenyans often dress in modern, American-style clothes—dark jeans, brand-name shirts with logos or designs and flat-brimmed hats. Many gay refugees dress this way too and tend to blend in with the crowd—though others, especially transgender people, stand out markedly and encounter verbal abuse and worse as a result. Many of the gay refugees have smartphones, and they're constantly sharing selfies. "I used to use Romeo," one Ugandan man tells me, referring to PlanetRomeo, the popular gay-dating app. "But then you find out someone else is hooking up with that guy in your same house. You don't find any other results."

"People who hook up with Kenyans, they use Grindr or something," another man tells me. "We did try using those apps. But Grindr became a risk. Very many people have been blackmailed."

One 19-year-old refugee tells me he was once lured into a date over WhatsApp, only to discover that it was a ploy by a group of homophobic Kenyan men. When he showed up, three men beat him, stole his money and phone, and left him bleeding on the floor.

Some refugees have found a way out. One young lesbian refugee from Kampala, Josephine, tells me she once tried to hang herself out of shame after she fell in love with a woman back in Uganda. Soon afterward, rumors of Josephine's sexuality reached her father, who sent a mob of neighbors to beat her. She fled to Kenya. In January, Josephine resettled in Chicago. She's found an apartment there, although she struggles to pay her rent, having found only intermittent work. Other refugees from the Rongai house have made it to the Netherlands, as well as to other U.S. cities.

Kato says officials at the United Nations, which handles the initial stages of the asylum process, have advised the gay Ugandans to keep a low profile while they wait. "Initially, we didn't think it would take that long," he says. "Keeping a low profile just means keeping indoors."

Kato has yet to receive the paperwork referring him to a foreign country's embassy for resettlement, and he has no idea if or when he will. "Someone can keep a low profile for two months, three months," he says. "But for two years you cannot be yourself? This is more like house arrest.

"Basically, our lives are on hold," he says. "When we are resettled, that's when we can hit Play."