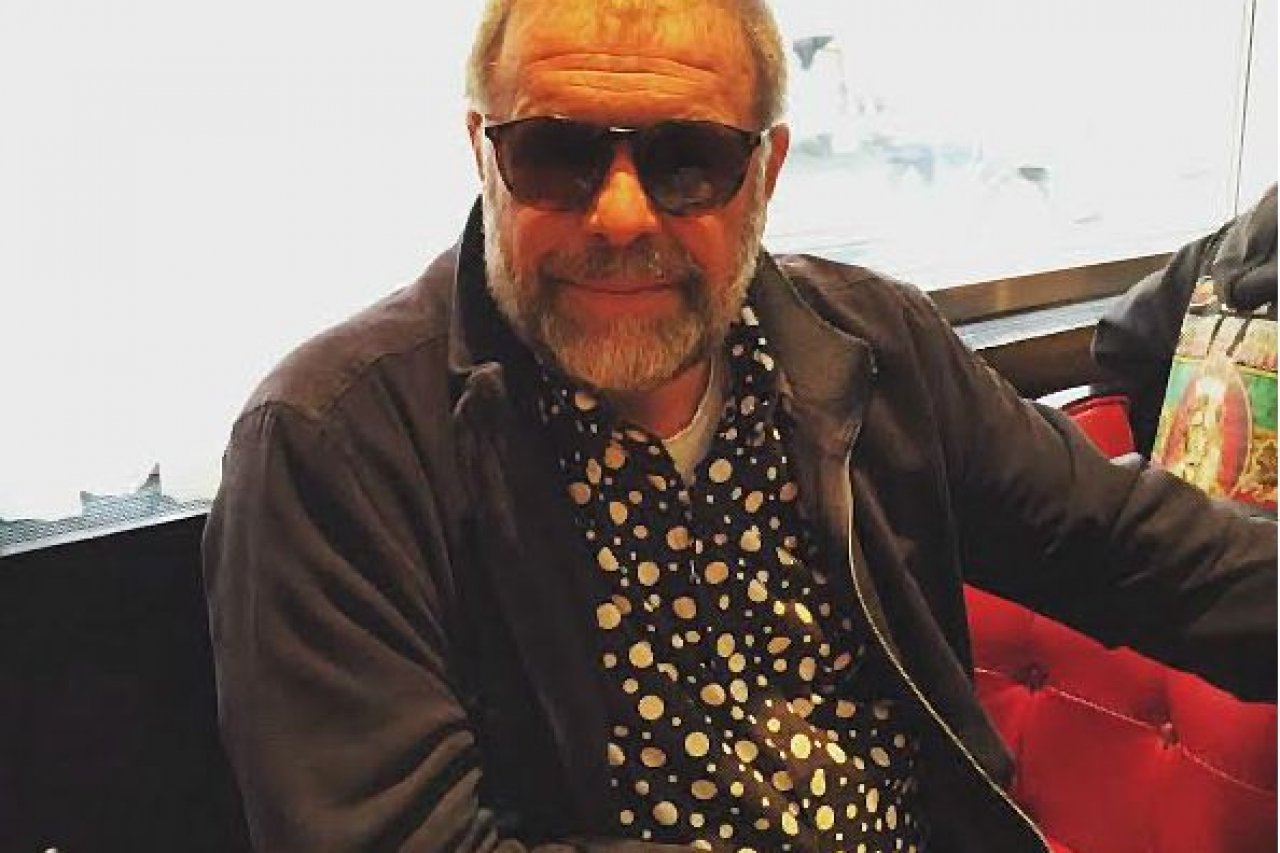

Updated | On Tuesday, May 19, hundreds of people lined up in front of the Webster Hall concert venue in Manhattan's East Village, and most of them were speaking Russian. Expats, first generation immigrants and tourists, they all came to catch Boris Grebenshchikov (who more spells his last name as Grebenshikov in English) on a rare American tour. He's the man who essentially invented rock music in Russia, and has been one of the most respected and influential singer-songwriters in the country for several decades.

Grebenshchikov, 61, who started making music in the early 1970's with his band Aquarium, is often described as the Russian counterpart to Bob Dylan. Though this label greatly oversimplifies both musicians' legacies, certain aspects of the comparison make sense. A fan both of British and American rock (from Dylan to Marc Bolan, Lou Reed to Talking Heads) and the Russian literary tradition, Grebenshchikov – usually referred to as BG - synthesized contemporary Western culture with his native Russian one, interpreting the foreign sounds in his own way and creating a unique sub-genre with his brand of highly sophisticated and metaphoric lyricism. Essentially, since the mid-1980's BG has assumed the role of the Russian Poet, an artist who put the nation's spirit into song. Many of his lines have become their own kinds of proverbs in Russian, and hardly anyone who tries to write a song with a guitar there can escape his influence.

At some point, BG tried to make it in America. When the Perestroika came, and the West became curious about the Soviet counter-culture, Grebenshchikov went to the U.S. to work with producer Dave Stewart, of Eurythmics, recording an English-language album, Radio Silence. The record managed to enter the Billboard Top 200, and BG even appeared on Letterman, but the breakthrough didn't quite land, and Grebenshchikov went back home to continue his Russian career.

Grebenshchikov's performance on David Letterman's show, 1989

It's a widely held belief that the Soviet underground rock scene, led by BG and Aquarium, played an important role in helping to bring the Soviet regime to an end. But apart from his Perestroika anthem "Train On Fire," Grebenshchikov has rarely expressed his personal political views or affiliations, either publicly or in his songs. However, just several months ago, he made an exception. The singer's most recent album, Salt, without specifically naming names, offers a grim perspective on contemporary Russia and the country's social climate. The catchiest song, for example, is called "Love in Wartime," and alludes to the conflict in Ukraine; one of the others, "The Governor," is considered to be about the governor of the Yekaterinburg region, who unfairly persecuted a local journalist.

The morning after his New York show, which lasted over two hours and included songs written as early as 1978 and as recent as this year, Grebenshchikov talked to Newsweek about his career, his long-lasting relationship with American culture and his views on current Russian events.

Western media usually refer to you as the "Russian Bob Dylan". What do you think of this?

Well, I was called all kinds of things—Russian Bob Dylan, Russian David Bowie, The Russian Clash—you name it…Of course, it's misleading. The thing that me and Dylan have in common is that we both are building bridges. Dylan built the bridge between the American traditional culture and pop culture, between folk and rock-n-roll. I have been trying to bridge between Western culture and Russia. As for everything else, well, I don't really care. Branding is a very shallow thing; it doesn't give people any idea of what the music really is. It's probably a bigger responsibility for Bob Dylan than for me. [Laughs.]

Still, you said several times that when you started writing songs, one of your purposes was to kind of translate Dylan's songs to Russian.

That's not entirely accurate. You can't translate American culture to Russian, because the conditions are very different. When I started writing songs for real, in the late 1970s, there was this one thing that was bothering me. When I listened to Dylan, or the Beatles, or the Rolling Stones, I felt like they knew how I felt and could express it. When I listened to music that was popular in Russia at the time, I couldn't find anything to identify with. I was going around, asking people, "What's wrong? Maybe I'm missing something." And they would tell me, "You aren't, but rock-n-roll can't be written in Russian, because the language just isn't suited for it." I thought, well, that's bullshit; let's see what can be done. So I started writing my own songs. And the results were quite good from the very beginning.

Ten years later, when you were already one of the biggest rock stars in the Soviet Union, you came to the U.S. and tried to make a music career here. By that time you had probably built a very detailed image of America in your head, drawing from your favorite records, books and movies. Do you remember what your impression was when you finally saw the real thing?

I remember it very well. New York was the first place I'd seen outside Russia. I was brought right to the center of the world. And I felt like Alice in Wonderland. I thought that all the miracles around me were here to teach me something. And there were so many pleasant surprises. For example, trees with little light bulbs on them – we didn't have that in Russia. Or, say, before coming to the U.S., I'd never thought of eating as something interesting. In Russia, food was something to be taken in without thinking about it. The idea that there was Japanese cuisine, or French, or Italian, was rather new to me—and I liked it, of course. I felt like I finally got to experience the real world. The world that had more colors in everything, unlike Russia, where people mostly had this black-and-white mentality. It was like a veil was suddenly taken off my eyes.

So did you perceive this whole American experience as a career opportunity, or was it just an experiment?

I came here to take part in an adventure. Ken Schaffer, a great mad New York music inventor, had this crazy idea of putting a Russian musician into the American cultural context. He found me, I fulfilled his expectations, and he brought me here. I hooked up with CBS Records, and then I found Dave Stewart, of Eurythmics. We did an album and a tour together, and then I went back home. You see, I wanted to see how things were done here. By that point I knew about it only from music magazines. I wanted to experience it first-hand, so that I could get back and do it the real way. And that's what happened.

A short excerpt from a documentary about the making of "Radio Silence," featuring Annie Lennox and Dave Stewart from Eurythmics, Chrissie Hynde, and Grebenshchikov.

And then you went back and recorded the most Russian record you've ever made, The Russian Album. Although it seems it would be more logical if you did something more Americanized…

Logical, yes. But thank God, music doesn't follow logic. You know, before I came here I had been in a cage. It was a nice cage, I can't complain; being in Russia in the 1970's and 1980's was great. But, of course, I wanted to breathe the air of the free world. Everything I recorded up to Radio Silence was basically a bridge between Russia and the West. When I got to the West, I felt the need to build a bridge back.

A lot of people are arguing right now that contemporary Russia is also a cage, comparing it to the Soviet times. What's your take on that?

I have to disappoint you. If you don't watch TV and spend your life on Facebook, if you go out on the streets of St. Petersburg and Moscow, there's a great feeling. It is changing, but for now it's still great. And from my perspective, it is still a free country. Of course, there is a lot of controversy. Just recently there was this Victory Day parade in St. Petersburg that seemed really impressive, but strange. The people weren't commemorating the fallen Russian soldiers; they were celebrating something completely different, some weird idea that was sold to them by the media. This is rather unfortunate, because I think this day deserves much more, but for now somebody is just using it for their own sake. On the other hand, when I walk around Moscow and St. Petersburg, I see a lot of bright young people who do their own little things and enjoy life. When I go to Kiev, I feel great; none of the bullshit you read about in the news, no hostility, and people are even more loving and tender than two years ago. Like somebody said, war is over if you switch off the TV.

One could say that all these bright young people exist in a designated ghetto surrounded by social hatred, war and lies. You can ignore TV and radio, but the majority of the Russian population doesn't.

True. But you see, it's always been like this. In the beginning of the 1990's, we were hypnotized. We thought: well, the great wall fell down, and now everybody is going to be happy and free, and everybody will listen to great music. In a few years, it turned out that people actually wanted prison songs. And now they have all this nostalgia about Soviet Russia and Soviet culture. And I'm like, hello? Do you really remember what it was? No, they don't, but they like it. It's not supposed to make them think, and it makes them feel better. All right. If you choose this, I don't have any problem with it. I don't have the right to judge. But there have always been, say, ten, fifteen, or maybe eight percent of the population, who need what we're doing, who have this demand for the real culture.

Still, the situation in the country is getting tougher for them. Some years ago, they at least could do their own thing and not be bothered. Now they're constantly being persecuted.

True again. But again, it has always been like this. Read the great Russian writers of the 19th century, that's how it was back then. And there's nothing wrong with it. Russians have always been fighters, even before they were baptized. There's a wonderful report of this Jewish merchant Ali ibn Yusuf who was employed by Arabs as a spy in, like, [the] 6th century, and they sent them to the territory that later became known as Russia. He wrote that people there are very good fighters, but they will never be a threat to anybody else, because instead of organizing themselves and going to conquer someone else they'd rather be fighting each other. And that's precisely what's going on right now.

You seem to have found your way to deal with the situation. But your last album, that was released only seven months ago, still sounds pretty dark and desperate. So dark, in fact, that your band doesn't even play most of the songs live.

I just couldn't resist the urge to do this album. It was in the air. For some time, I became obsessed with what was going on. I was full of anger and despair, and that's how these songs were born. It has quickly become one of the most popular albums we've ever done. It touched the nerve. I did the right thing, but it was painful. We played this album live for three months, and then said bye-bye to it. We paid our dues to today, let's go back to tomorrow. Because what I'm trying to do now is to build another bridge, between today and the day after tomorrow. Tomorrow is very uncertain; I don't have high hopes for it. But the day after tomorrow is going to be all right.

Do you think that music can still be instrumental in terms of changing society? I mean, as instrumental as Soviet rock was in bringing down the Soviet Union in the late 1980's?

I believe that, today, music is even more important. Good music is preserving the sanity of people. You know, the ten percent I mentioned, and maybe the children of the ninety percent that at the moment are quite aggressive and in the dark, their children are going to be different. At least, I hope so.

So you're not discouraged? It seems that you don't buy the argument that the whole cultural project that Russian liberal-minded intellectuals have been trying to create since the late-1980's failed.

No. There was no project, and, you know, Lao-Tzu cannot be defeated. What we have been doing from the beginning is just a natural extension of what poets of the Silver Age did. There's no real difference between Turgenev and us. We both belong to the Russian culture that is not affected by the bullshit.

This story has been updated to include the name spelling Boris Grebenshchikov uses in the United States.