Your skin is teeming with microbes. Millions of them. From the perspective of these tiny organisms, the surface of your body is their living, breathing habitat. This living layer is part of what's called the human microbiome—the collective genomes of all the "foreign" microorganisms that live in the human body—and research on it has exploded in recent years. But within microbiome research is a brand-new field that is just beginning to understand a stunning fact: Your microbiome extends beyond yourself, into the air around you. It hovers in a cloud around your body and leaves bits of itself on surfaces wherever you go. In short, you have an aura, except it isn't made of purplish light; it's your personal cloud of dead skin cells, fungus and many, many microbes. And researchers are learning to be able to identify you by it.

"You know the dirty kid from Peanuts? Pig-Pen? It turns out we all look like that," says James Meadow, a data scientist at Phylagen, a company in San Francisco that focuses on improving the health of the indoor microbiome in places like hospitals and homes. (All sorts of people, places and things can have their own microbiomes.) "We give off a million biological particles from our body every hour as we move around. I have a beard; when I scratch it, I'm releasing a little plume into the air. It's just this cloud of particles we're always giving off, that happens to be nearly invisible."

Related: Distinctive Microbiome Associated With Schizophrenia

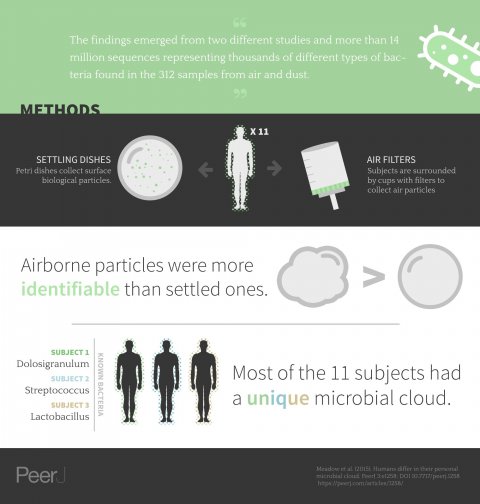

On Tuesday, Meadow and his colleagues published a paper written while he was a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Oregon. In it, he and his research partners sampled the air surrounding 11 different people in a sanitized experimental room and sequenced the microbes emanating from them. They determined that an occupied room is microbially distinct from an unoccupied one. What's more, after three people spent four hours in a room together, giving off their microbes into the air and onto surfaces, Meadow's team was able to distinguish each person based just on the bacteria in the surrounding air. "Each occupant's personalized airborne signal can be statistically differentiated from other occupants," they wrote.

"This was a first stab at it to see if it was possible. We didn't expect to be able to tell people apart," Meadow says. "It kind of blew us away."

Among other differences between people's microbial cloud "signatures," one that stood out was their gender. The researchers were able to identify when a woman was in the chamber because the microbes in the air around her included Lactobacillus, a type of bacteria that is typically found in abundance in the environment in a woman's vagina.

In large part, you can thank your body heat for generating your unique microbial cloud. Heat rises off the body, propelling the particles outward. Your breath, which is part of your microbiome, is also hot and can push particles out too. The size of your cloud will have to do, in part, with how hot or cold your body temperature is at the moment.

You're 100 Percent Wrong About Showering

How far the cloud reaches is all dependent on the "viscosity of the air," according to Meadow. "We can only feel air when it's hitting us. But for something that tiny [a microbe], air is more like water. If there's any little bit of movement, they can just float around the room indefinitely. The tiniest bacteria can be picked up and stay in the air for hours," he says. "Even just sitting at your desk, your cloud is probably reaching to your neighbor."

Understanding the interplay between the microbial cloud and environment could form the basis for attempts to better engineer indoor spaces to prevent the transmission of diseases. "We could potentially design our buildings around that. If we know there's an airborne disease risk, maybe we could develop ventilation accordingly," says Meadow. Places like hospitals or offices could stand to benefit, for example.

Another potential real-world application for microbial cloud research is forensics. We already know, for example, how to distinguish between the bacterial fingerprints people leave on their computer keyboards. And while it may be "years down the road," Meadow says, our ability to distinguish between people based on their airborne microbial signatures will likely get better and better. "I can think of all kinds of reasons why we'd want to know if a nefarious character had been hanging around a room." Plus, researchers already know that the skin microbiome differs according to where a person lives, so chances are good their microbial cloud does too. "It might be able to tell us where they've been."

Dr. Martin Blaser, who was not involved in the study, agrees. Blaser is the director of NYU's Human Microbiome Program and considered one of the foremost experts in the field. "Just like the detectives today are dusting a room to look for fingerprints, maybe [in the future] they'll take a big vacuum and see what microbes are there. It's certainly not tomorrow, but it might be possible."

Blaser also wonders what the future implications might be for privacy. "I think it's just like people looking at your electronic data. But there may be a more concrete microbial signature. Privacy potentially could be breached in many realms. We're very concerned about electronic privacy, but we have [other] signatures [too]."

Related: L'Oréal to Start Printing 3-D Skin With Bioengineering Company

Still, there are many more basic unanswered questions. For example, Blaser says, researchers still don't know whether taking antibiotics would totally rearrange a person's microbial cloud, to the point of not being able to distinguish them.

While microbial cloud research is in its earliest stages, Meadow says he is "100 percent convinced" that "this, along with the genome sequencing revolution, will give us better health."

But, he says, "we need to be very careful about who gets that information about all of us."