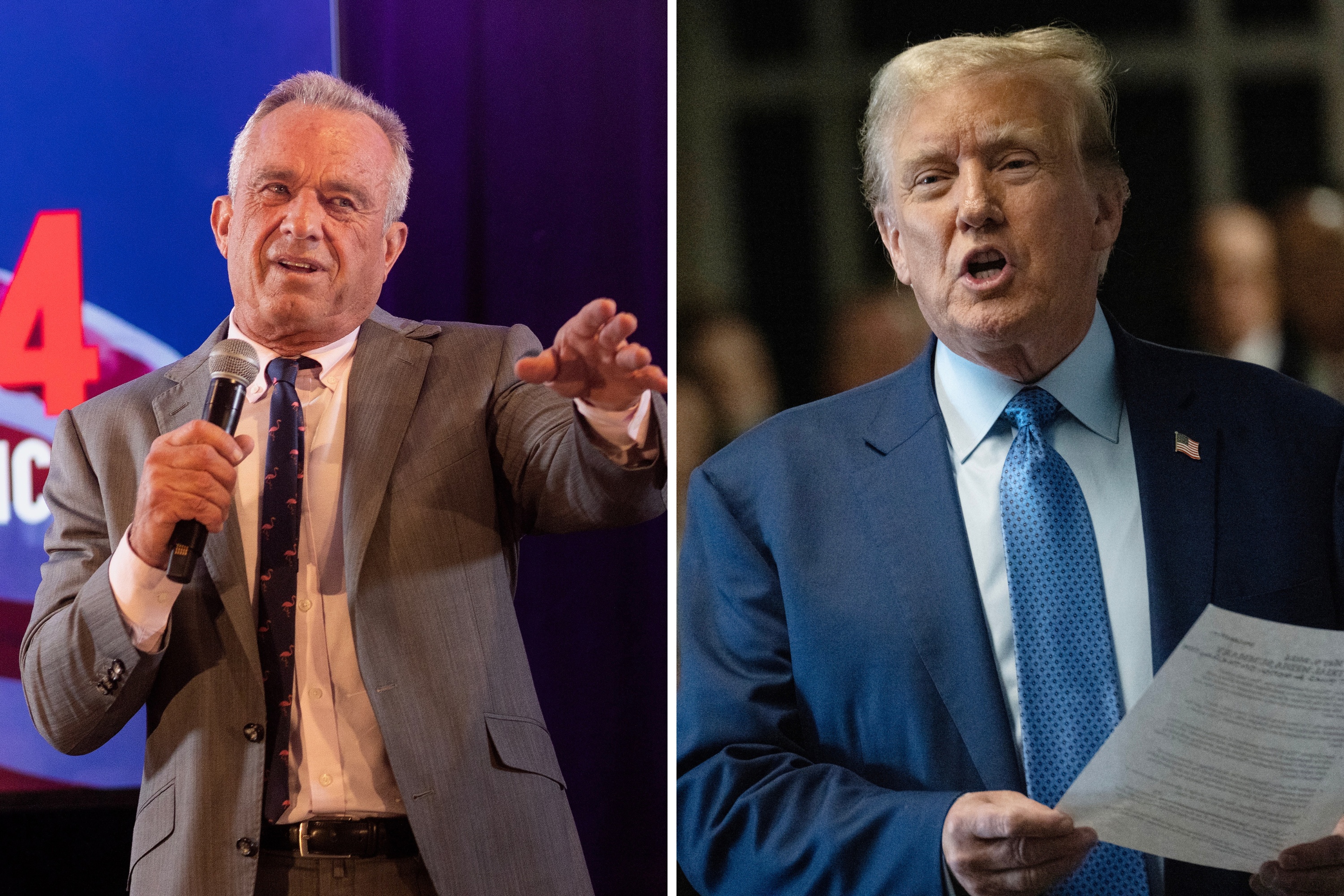

Archaeologists have uncovered the missing upper part of a "huge" statue depicting an ancient Egyptian pharaoh.

A joint Egyptian-American archaeological mission discovered the statue part during excavations conducted in the vicinity of el-Ashmunein, a town in the Minya governorate, the country's Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities (MTA) said in a statement.

Just outside the modern town lies the archaeological site of the ancient city of Khemenu, or Hermopolis Magna, which had been a provincial capital since Egypt's Old Kingdom and developed into a major settlement during the Roman period.

The upper part of the statue uncovered by the archaeological mission at el-Ashmunein—a collaboration between Egypt's Supreme Council of Antiquities and the University of Colorado—depicts King Ramesses II.

The statue part was discovered in a temple at the southern border of the Khemenu/Hermopolis Magna archaeological site, Yvona Trnka-Amrhein, one of the leaders of the mission, told Newsweek.

"This would have been a relatively central area of the ancient city," the archaeologist said.

The part is made of limestone and stands around 12 feet in height, said Basem Gehad, head of the Egyptian side of the mission. It shows the king sitting, wearing a double crown and a headdress topped with a royal cobra. The upper part of the statue's back column features hieroglyphic text detailing titles glorifying the ruler.

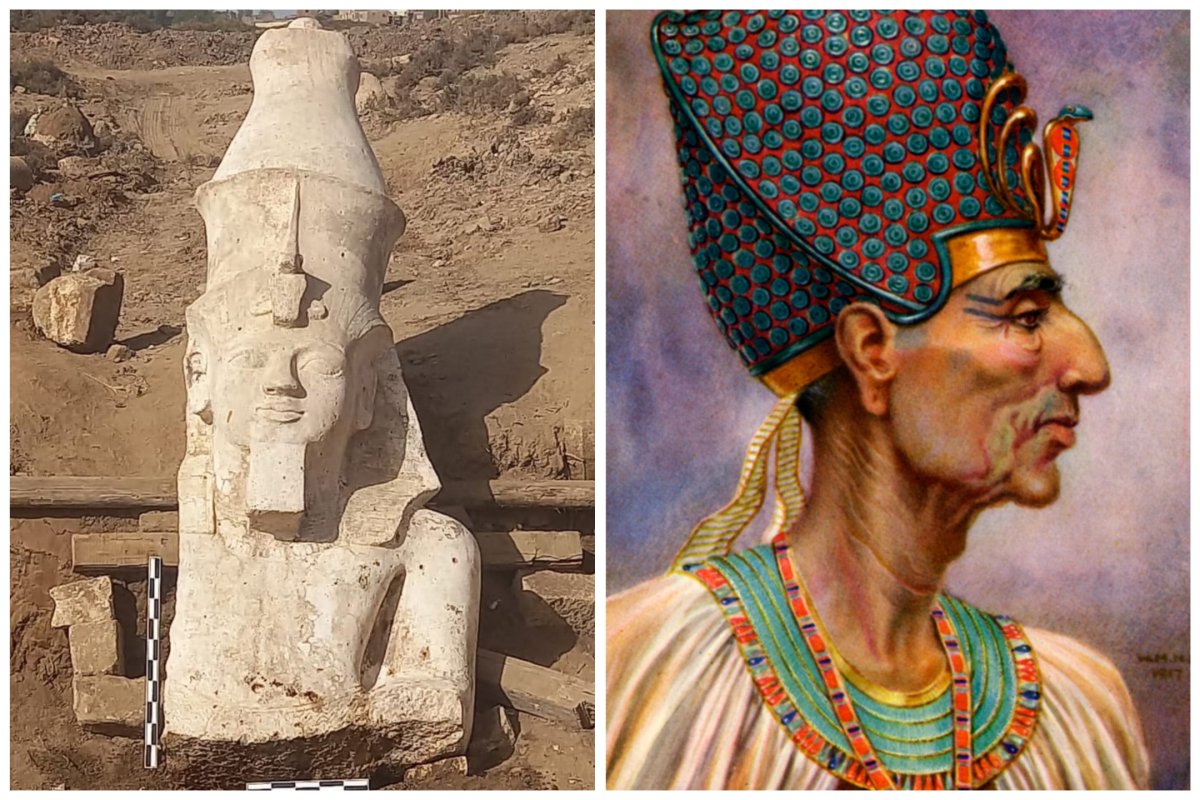

The pharaoh, often referred to as Ramesses the Great, ruled between 1279 B.C. and 1213 B.C. during the New Kingdom, generally considered to be the period when ancient Egypt was at the height of its power and prestige.

In fact, Ramesses II is often regarded as the most powerful pharaoh of the New Kingdom and is notable for conducting more than a dozen successful military campaigns.

During his reign, the second longest in Egyptian history, Ramesses II carried out extensive building programs, and numerous huge statues of him are found all over the country. The pharaoh is thought to have lived to around 90—an exceptionally long time by ancient Egyptian standards.

An archaeological study of the upper part of the statue from el-Ashmunein determined that it was a continuation of a lower section discovered by the German Egyptologist Günther Roeder in 1930. If both sections were joined together, evidence suggests that the statue would have reached around 23 feet in height.

"On art historical grounds, the statue can be dated to the later reign of Ramesses II," Trnka-Amrhein said.

It is only the second colossal statue to be found in Middle Egypt—where Khemenu/Hermopolis is located—though many are known from major pharaonic sites such as Karnak at Luxor, according to the researcher.

"This does not mean that there were no colossal statues erected in Middle Egypt. Khemenu was an important site for the worship of Thoth, the Egyptian god of writing and wisdom, and it was originally crowded with temples and imposing monuments. Our discovery will help show how Middle Egypt fits into the architectural and religious landscape of Ramesside Egypt (1295-1069 B.C.)," she said.

The recent excavations at Khemenu/Hermopolis began in an attempt to uncover the religious center of the ancient city during the New Kingdom until the Roman era. The discovery of the statue part indicates the importance of the site, which will likely reveal more archaeological discoveries in the near future, according to the MTA.

Do you have a tip on a science story that Newsweek should be covering? Do you have a question about archaeology? Let us know via science@newsweek.com.

Update 03/22/24, 1:49 p.m. ET: This article has been updated to include additional comments from Yvona Trnka-Amrhein.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Aristos is a Newsweek science reporter with the London, U.K., bureau. He reports on science and health topics, including; animal, ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.