Some of the secrets of the moon's long history, feared lost to time, may have been revealed in moondust samples brought back to Earth by China.

3.8 pounds of moondust, also known as lunar regolith, were brought back by China's Chang'e-5 in late 2020, marking the first lunar sample returned to Earth since the Soviet Union's Luna 24 in 1976.

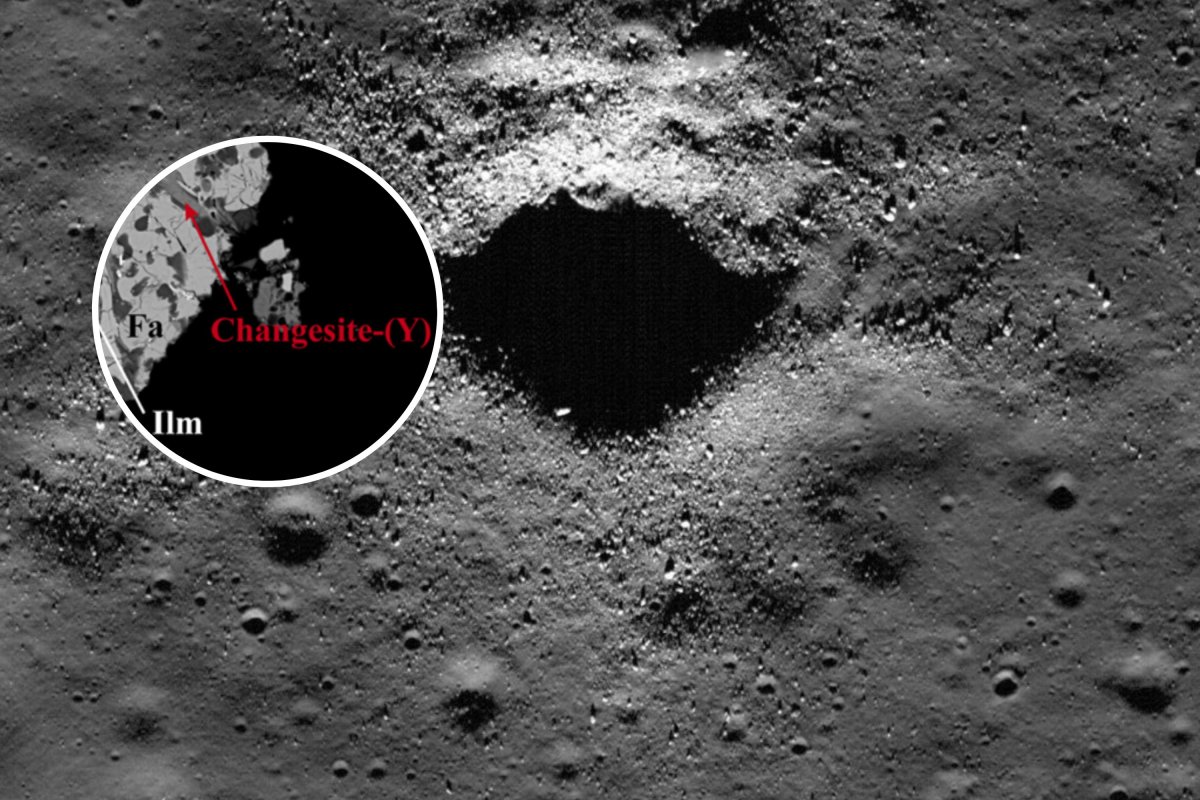

The samples revealed several strange silicate minerals, and also the presence of a brand new mineral, Changesite-(Y), according to a new paper in the journal Matter and Radiation at Extremes. It is hoped that these chemicals will help the researchers figure out details of celestial objects crashing into the moon's surface throughout its history.

Chang'e-5 landed in an area of the moon called the Oceanus Procellarum, situated in the northwest of the moon as seen from Earth. Many of the rocks in the sample were found to be roughly 2 billion years old, which is much younger than the 3.1 and 4.4 billion years old samples brought home by NASA's Apollo astronauts.

As asteroids and tiny space rocks slam into the surface of the moon at high speeds, there are huge spikes in the temperature and pressure in the lunar soil at the point of impact. These conditions alter the structure of the moondust, leading to the formation of quartz-like silica minerals like stishovite and seifertite.

"Although the lunar surface is covered by tens of thousands of impact craters, high-pressure minerals are uncommon in lunar samples," paper author Wei Du, a geochemistry researcher at the Chinese Academy of Sciences, said in a statement.

"One of the possible explanations for this is that most high-pressure minerals are unstable at high temperatures. Therefore, those formed during impact could have experienced a retrograde process."

The Chang'e-5 sample contained a whole new lunar mineral named Changesite-(Y), which was found to be a phosphate mineral with a structure composed of colorless, transparent column-shaped crystals.

The sample was also found to contain a mineral made of both stishovite and seifertite. This should be impossible, the researchers say, as they should theoretically only both form at much higher pressures than were thought to occur at the sample site.

The scientists suggest that the seifertite formed as a phase between stishovite and another silica mineral named α-cristobalite.

"In other words, seifertite could form from α-cristobalite during the compressing process, and some of the sample transformed to stishovite during the subsequent temperature-increasing process," said Wei.

The collision that would have triggered this process was determined to need a peak pressure of between 11-40 GPa, and last between 0.1 and 1 seconds. The researchers estimated that the crater formed by that collision would have been between 1.9 and 19.9 miles across.

Based on this, the researchers think that the mineral may have originated from the collision that formed the Aristarchus crater, and been flung to the site of Chang'e-5's sample.

"Considering that both seifertite and stishovite are easily disturbed by thermal heating, Aristarchus (formation age: around 280 million years ago), which is the youngest among the four distant craters and has silica-rich materials exposed in its interior, rim, and ejecta, is the most likely candidate for the source of the host rock of seifertite and stishovite," the authors wrote in the paper.

The researchers hope that these mineral samples might be able to give more insight into the history of the moon and its meteorite impacts over the years.

"New minerals discovered in lunar returned samples and lunar meteorites can also reflect their formation conditions, providing key information about the magmatic activity, thermal evolution, and impact history of the moon," the scientists wrote in the paper.

Do you have a tip on a science story that Newsweek should be covering? Do you have a question about moondust? Let us know via science@newsweek.com.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Jess Thomson is a Newsweek Science Reporter based in London UK. Her focus is reporting on science, technology and healthcare. ... Read more