Just one day after successfully completing the first-ever flyby past Pluto, NASA's New Horizons team has already seen images 10 times better than one taken Monday afternoon and made some important observations as a result. They shared and discussed the most detailed image produced of Pluto to date—taken an hour and a half before the Tuesday morning flyby—at a press briefing Wednesday afternoon at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory in Laurel, Maryland.

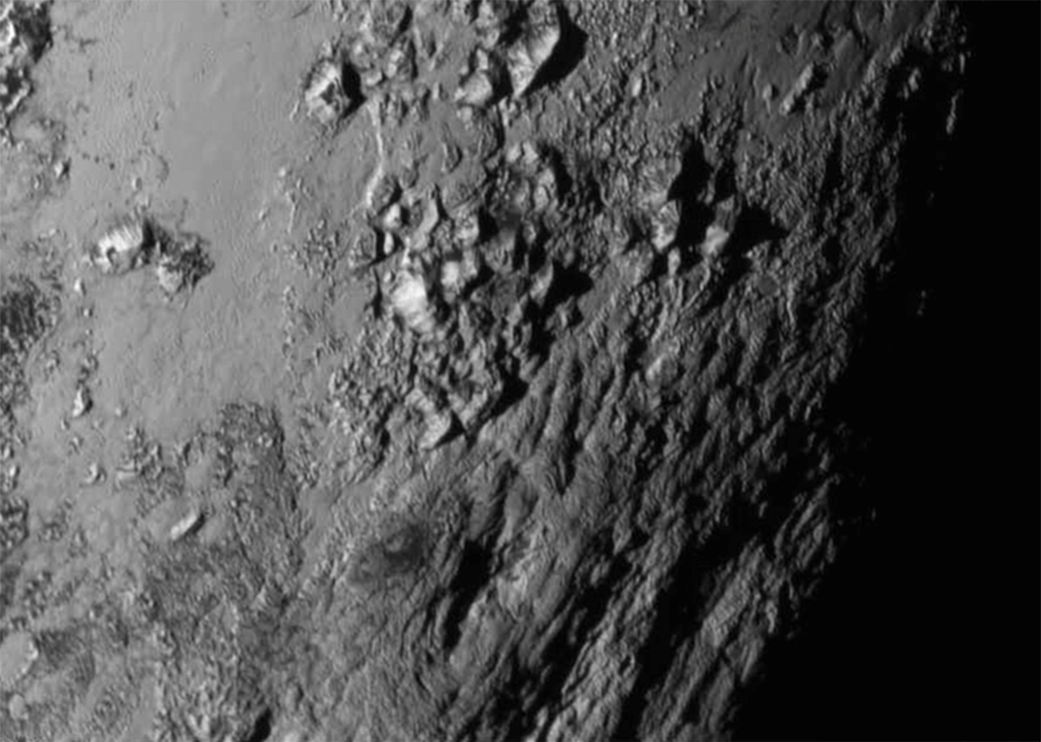

The new image zooms in on one small section of Pluto's surface at the bottom of the bright heart-shaped region that has captured the attention of both scientists and the public. The team has informally named that region Tombaugh Regio, principal investigator Alan Stern said, in honor of the man who discovered Pluto in 1930, Clyde Tombaugh.

The detailed image shows a range of mountains, some of which rise up to 11,000 feet above Pluto's surrounding surface. Since methane ice and nitrogen ice, which cover much of Pluto's surface, are not strong enough materials to form such tall mountains, the peaks are likely made out of water-ice.

"At Pluto's temperatures, water-ice behaves more like rock," Bill McKinnon, deputy geology, geophysics and imaging (GGI) lead, is quoted as saying on NASA's website.

One of the most striking aspects of the new image, geologically speaking, is there doesn't appear to be even a single impact crater, explained John Spencer, a deputy leader of the GGI team. Because Pluto has likely been bombarded by debris in the Kuiper Belt, the lack of craters suggests that Pluto's surface is no more than 100 million years old, younger than expected and striking when compared with the solar system's 4.56 billion years. The young surface, in turn, suggests there may have been recent geological activity that made the impact craters from those bombardments indiscernible.

This comes as a surprise to scientists, because it means the dwarf planet appears to be powering its own geological activity, Stern explained. These sorts of processes—such as tidal heating—typically occur when one astronomical object orbits a larger object. But Pluto does not orbit around a giant planet, and Charon—the largest of Pluto's five moons—is not big enough to exert that kind of influence. Geological activity, then, apparently can be ongoing on icy worlds even without "gravitational interactions with a much larger planetary body."

"That's a really important discovery that we just made this morning," Spencer said.

NASA published a very brief animation to show exactly which region has been captured in the new image. According to Spencer, this is just the first piece of a larger mosaic. "We've got a whole bunch of high-resolution observations safely on board the spacecraft," he said. "This is just one small taste."

In addition to the zoomed-in image of Pluto, the team received its best-ever image of Hydra, Pluto's outermost, irregularly shaped moon, which enabled them to determine its dimensions (27 by 20 miles) and other basic physical properties for the first time. Finally, they shared a new image of Charon.

"Charon just blew our socks off," said Cathy Olkin, deputy project scientist. "All morning the team has just been abuzz." Olkin described a dark area near the moon's north pole, which the team has informally named Mordor, after the region described in J.R.R. Tolkien's Lord of the Rings. It has a reddish coloring that diffuses at the edges, and the team believes this may be a thin deposit of dark material, a "veneer" as Olkin called it.

She also pointed out a series of troughs and cliffs running roughly 600 miles across the surface of Charon and a canyon four to six miles deep at the upper right (at about the 2 o'clock position). Images of some regions of Charon at a resolution five times that of the image shared Wednesday are still to come, Olkin said.

Less than two days have passed since New Horizons's closest approach to Pluto, and the data have just started coming in. So far, Stern said, "I don't think anyone of us could have imagined it was this good of a toy store."

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Stav is a general assignment staff writer for Newsweek. She received the Newswomen's Club of New York's 2016 Martha Coman Front ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.