Nick Cave knows death. He's traversed the subject with rich and disturbing familiarity. His father, a schoolteacher, died in a car crash when Cave was 19 and jailed for a petty crime. Years later, "The Mercy Seat," a grim account of a condemned man awaiting the electric chair, became his trademark song. (Johnny Cash brought the song added resonance when he covered it a decade later, as he faced down his own declining health.) Cave's best album climaxes with a feverish imagining of his demise and funeral titled "Lay Me Low." His best-selling album, 1996's Murder Ballads, delights in its titular theme like a Tarantino script; Cave's characters get shot ("Stagger Lee") and chucked into wells ("Henry Lee") and bound with electrical tape and stabbed ("Song of Joy"). It's bloody good fun, emphasis on bloody.

That cartoonish glint, the cinematic distance—there is none of that on Skeleton Tree, Cave's 16th album with the Bad Seeds and first since the sudden death of his 15-year-old son, Arthur. Brief and intense, this set of songs lives in the haunted space between mourning and acceptance. Cave's imagery is as evocative as it's ever been. On "Girl in Amber," a dirgelike puzzle of a song, he confesses he "used to think that when you died you kind of wandered the world/In a slumber till your crumble were absorbed into the earth." (Whether he means the generic "you" or a specific vision of his son's departure is left ambiguous.) And though there is not a banal molecule in Cave's body—the man refuses to be photographed in less than a tailored suit—Skeleton Tree and its accompanying film, One More Time With Feeling, capture with extraordinary vividness the most ordinary dimensions of grief: vomiting in the sink ("Magneto"), unraveling in the grocery line (two songs here reference the supermarket), wondering when you became an object of pity.

Grief is transformative. Literally so—it can wreck your skin, produce bags under your eyes, give you a chest cough. In One More Time, Cave muses on how trauma can force change on an individual. "What happens," he wonders in semi-improvised voice-over, "when an event occurs that is so catastrophic that we just change? We change from the known person to an unknown person." So he does; Cave, the towering post-punk prince of darkness, who once chucked a glass at a nosy journalist, changes, appears more emotionally vulnerable here than he has been before. The film makes a stark contrast with 2014's 20,000 Days on Earth, which blurred reality in the form of a fictionalized day in the life of the rocker.

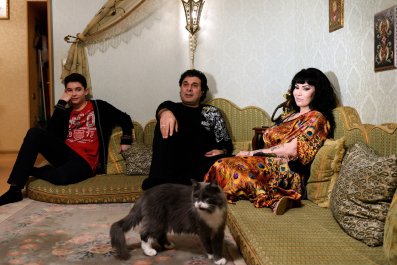

One More Time With Feeling hits something closer to cinema verité. Cave and his wife, Susie Bick, cope with the unspoken loss in black-and-white snippets that are candid and sometimes even funny and often terribly sad. She tears up while revealing a painting their son made as a child depicting the spot near the cliff where he fell to his death in 2015. These scenes are interspersed with studio performances from the making of Skeleton Tree. Early on, we see Cave laying a vocal track for "Jesus Alone," the record's eerie, hallucinatory opener. Bandmate Warren Ellis conducts the droning swells of a string section with feverish gestures. The song reportedly was written pre-2015. Yet its opening imagery—about someone or something falling from the sky and crash-landing in a field—carries prescient weight in light of Arthur's death. It's classic Cave, urgent and pitch-black noir, yet doesn't quite sound like anything he's written before.

The confessional tone of these songs will remind some of the 1997 masterpiece The Boatman's Call, but the musical arrangements owe more to 2013's Push the Sky Away, with Cave's band experimenting with loops, sparse synth designs and even some frenetic drum programming ("Anthrocene"). The singer's signature piano is ever present but hardly dominant. "Rings of Saturn," a dreamlike, rap-inspired vision, follows the last record's "We No Who U R" with twinkly keyboards and processed rhythms. Longtime guitarist Mick Harvey's 2009 departure marked a serious rupture in the Bad Seed ranks, but Cave has used it to his advantage. He has gone quiet without reverting back to his Boatman/No More Shall We Part piano-balladeer persona. The record is full of open spaces and odd sonic touches. On "Magneto," his voice drifts down to a great, quavering baritone as flutters of bass and feedback swim around him.

"I Need You," the song that is most explicitly prompted by Arthur's loss, stands as Skeleton Tree's centerpiece. It is one of Cave's most wrenching performances to date, a painful upper-register crooning that's enough to imbue a mantra as clichéd as "Nothing really matters" with the full-throated hollowness of grief. "Skeleton Tree," the autumnal closing track, feels like dawn after the storm, much the way "New Morning" closes 1988's Tender Prey. There are visions of light: a window, a candle, a "jittery TV" glowing white. Skeleton Tree is filled with deep sadness, but it's a testament to Cave's craft that he manages to end such a bleak statement with some faint shadow of sunlight.

What's obvious is that there is no alumnus from the post-punk generation nearly as tenacious or adaptable as Cave. At 58, he has been at work longer than most present-day pop stars have been alive, and though he gets written off every so often, he seems to scale some new creative peak every goddamn decade. The man keeps his distance: He doesn't tweet, rarely suffers himself through interviews and, like a great Method actor, seems existentially incapable of breaking character or costume. Now he's suffered a great tragedy and emerged with one of 2016's great albums. You never really know what he's thinking. But with Skeleton Tree and its documentary counterpart, we get a remarkably moving glimpse of what he's feeling.