It was a hot February day on the U.S.-Mexico border when an observant customs officer noticed that a teenager crossing the Otay Mesa checkpoint had a suspicious bulge in his crotch. When officers escorted the 19-year-old out of the pedestrian lane and patted him down, they found a package in his underwear holding what they thought were almost 1,200 oxycodone pills.

But tests that were run after the arrest by a Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) lab revealed the pills were counterfeits composed of fentanyl—an extremely potent drug that dealers have cut into heroin for at least a decade to boost that narcotic's potency.

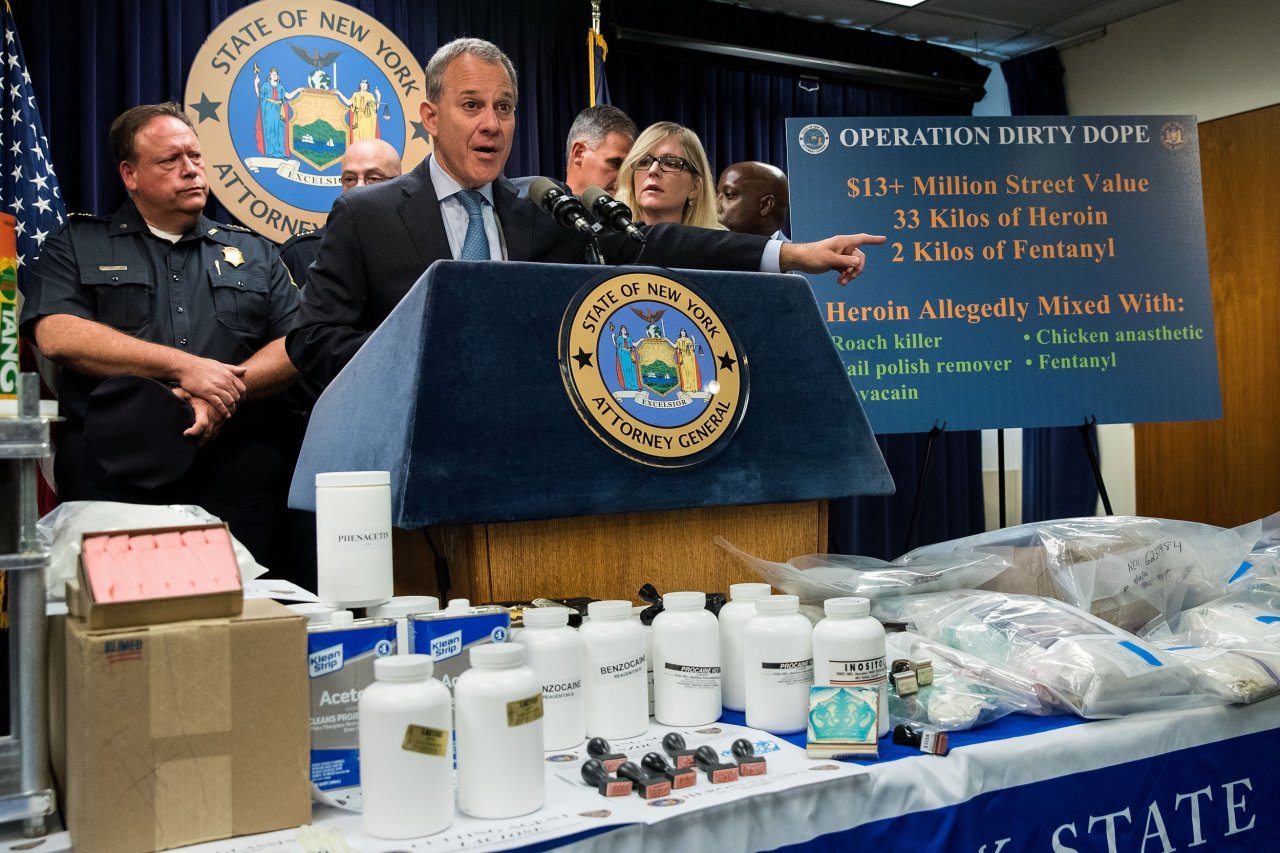

That arrest on the border between Tijuana and San Diego illustrates two new trends in the U.S. opioid crisis, authorities say. First, it's an example of the scary rise over the past few years in the amount of fentanyl being smuggled into the U.S. from Mexico. Second, it shows that criminals are increasingly pressing fentanyl into counterfeit prescription pills and selling them in the U.S. "When you have a seizure like that, it's not going to be isolated. It's not one person in Mexico making 1,000 pills," San Diego federal prosecutor Sherri Hobson tells Newsweek , adding that this was the first seizure of counterfeit oxycodone that contains fentanyl across the Southwest border. "The Mexican drug traffickers [realized] there's money to be made in smuggling fentanyl," Hobson says. "It's an emerging trend, but it's deadly."

Fentanyl is flooding across the border in both powder and pill form. A drug-sniffing dog perked up at the passenger door of a white Chevy pickup truck at the Tijuana–San Diego checkpoint in July, leading customs officers to almost 6,000 pills labeled oxycodone. Once again, they turned out to be counterfeit pills composed of the even more dangerous drug, fentanyl. "We are extremely troubled by the number of fentanyl seizures we've seen recently," San Diego U.S. Attorney Laura Duffy said in a statement in late September. She cited three separate arrests of men who tried to drive powdered fentanyl across the border in September, including one who hid 19 pounds of it in a spare tire and another who concealed 33 pounds in a secret compartment.

The U.S. is in the middle of an opioid epidemic. More than 28,000 people died of opioid overdoses in 2014—the most recent year on record and more than any past year, according to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The crisis has even become an issue on the presidential campaign trail, with Democratic nominee Hillary Clinton detailing a $10 billion plan to fight drug and alcohol addiction on her website and Republican Donald Trump telling a cheering New Hampshire crowd last month, "I'm going to stop the drugs from pouring across the border, and that's a promise."

Like any smart retailer, Mexican drug cartels have responded to ever-soaring demand for prescription drugs like the painkillers oxycodone and Norco by manufacturing cheaper alternatives using fentanyl, which they buy from China, along with the undeclared pill presses necessary to stamp out the fakes. China is the primary source of fentanyl sent to Mexico, the U.S. and Canada, according to the DEA. The surge of fentanyl use has had deadly repercussions, with 700 people dying of the drug between late 2013 and late 2014, according to the DEA.

Experts say people who have OD'd on fentanyl often thought they were injecting or ingesting heroin or a genuine prescription pill but were hit with a drug that's 25 to 50 times stronger than heroin. South Carolina restaurant worker Scott Davenport had been clean of heroin for two years when he relapsed in March 2015 and bought what he believed was heroin. "For whatever reason, he decided one last time to go back and do what his drug of choice was, heroin, and I'm sure he thought he was buying heroin, and somebody sold him 100 percent fentanyl," Davenport's father, Roy, told Newsweek in April.

When Davenport injected the fentanyl, he died almost instantaneously. "I got that phone call no parent ever wants to get," recalled his father. "Someone from the restaurant where he was working called and said, 'I hate to be the one to call you, but we just found your son unconscious in the bathroom.'"

The massive profits that can be made with fentanyl dwarf the money that can be made with heroin or oxycodone. A kilogram of fentanyl can make 1 million pills that can sell for up to $20 million, according to the DEA. With chemical distributors in China selling fentanyl for around $3,500 per kilogram, traffickers have a huge incentive to continue smuggling the drug across the border.

Roy Gerona has run a toxicology lab at the University of California, San Francisco, since 2011, where he tests pills to determine whether they contain fentanyl and other designer drugs for poison centers, medical examiner's offices and government agencies, including the DEA. "The Norco incident was the first time that we saw fentanyl in pill form," the assistant professor says, describing when his lab tested pills from the Sacramento overdose outbreak that killed 14 people in March and April. "If you popped one of those pills, you're ingesting the equivalent of more than 30 Norco tablets, and you will definitely overdose."