Obada Nawawra was talking to friends at a restaurant in Bethlehem. Outside the window, the terraced hills around the ancient West Bank city rolled into the distance. It was early June, and most restaurants were closed for Ramadan; aside from a table of tourists, the large place was nearly empty. As the conversation shifted to the subject of the Palestinian Authority (PA)—the semi-autonomous government based in the Israeli-occupied West Bank—the idle waiters edged closer to Nawawra's table.

The 25-year-old was staking out a historically mainstream position: The PA is an important institution for keeping peace in Palestinian enclaves. "Without the authority," he said, there would be lawlessness—"more crime and drugs." A boyish-looking waiter was incredulous: "How is the authority good? Before it, was there more crime? Another waiter, a woman who looked to be in her 20s, answered, "No!" Other restaurant workers added their disapproval—an increasingly popular attitude among young Palestinians.

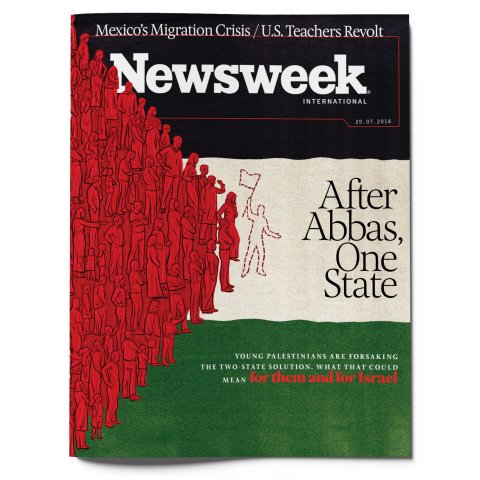

After years of allegations of corruption and collusion with Israel, the PA is viewed with increasing distrust by this generation. Their parents dreamed of a Palestinian state and an end to Israeli occupation. But they have watched as illegal Israeli settlements spread. They have listened to the drumbeat of extreme-right Israeli politicians, like those in the Likud party, calling for a "Greater Israel," which would take territory back rather than give it away. They have watched as the Arab world has grown closer to Israel, turning its attention toward the threat of Iran.

These fears have taken on a new urgency. In January, President Donald Trump cut off funds to the United Nations Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA), which aids and represents Palestinian refugees in the Middle East. A month before, he had announced that the U.S. Embassy would move from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem in May, a clear message that his administration was officially and unequivocally siding with Israel. Jerusalem includes sites sacred to Muslims as well as Jews and Christians, and Palestinians have claimed East Jerusalem as the capital of their future state—borders laid out in 1993's Oslo Accord or Arab-Israeli Peace Process, which established Palestinian self-rule in the Gaza Strip and the West Bank. After decades of U.S.-led Israeli-Palestinian negotiations, Trump's decision undercuts America's credibility as a neutral party, deflating further hope of a peace treaty. Complicating matters further: Twelve years into what is nominally a four-year term, PA President Mahmoud Abbas is ailing, and there is no clear succession plan.

The once unspeakable idea of a binational Israeli-Palestinian state gained popularity among young Palestinians several years ago—a sharp departure from the mainstream two-state solution. One state, of course, means different things depending on whom you're talking to. For the right-wing Israeli government, one state would mean annexation and segregation of Palestinians; anything else implies the end of the Jewish state. For many older Palestinians, one state only suggests further violence, even civil war, as well as the real possibility that the balance of power would stay with Israel and they would remain second-class citizens.

But for young Palestinians intent on equal rights, the intention is a single democratic country encompassing all of the current territory of Israel, the West Bank and possibly the Gaza Strip and Golan Heights. This generation is willing to risk violence because its members grew up with it. They came of age during the second intifada of the mid-2000s, when Israel retook Palestinian cities in the West Bank. The brutal campaign, orchestrated by suicide bombers, cost the lives of 6,371 Palestinian and 1,137 Israelis; on both sides, at least half of the victims were civilians who did not participate in the hostilities.

The causes were long-simmering frustrations over the ongoing Israeli occupation and the lack of economic development promised in the 1993 accord. That treaty, between Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) leader Yasser Arafat and Israel, was intended as a five-year interim step toward the plan for a Palestinian state. In the 23 years since, efforts at peaceful negotiation have amounted to nothing. Worse, Palestinians are now sharply divided, between a secular, internationally backed party, Fatah, and the theocratic Hamas, an offshoot of Egypt's Islamist Muslim Brotherhood. The parties effectively share the same goal—a Palestinian state—but while some within Hamas would be willing to accept borders established in 1967, the more militant majority supports armed resistance (Jewish genocide is written into the Hamas charter).

Hamas, which has been designated a terrorist organization by the U.S., EU and Canada, won the 2006 parliamentary elections. For many voters, it was less an endorsement of the Islamic party than a message to Fatah of extreme displeasure over party corruption, internal divisions and perceived collusion with Israel. Fatah rejected the victory. A resulting armed conflict, in 2007, left Hamas controlling the Gaza Strip, and Fatah the West Bank.

To get closer to the dream of statehood, Abbas has been pushing for his people to join international organizations like UNESCO and to maintain close relations between Israeli and Palestinian security forces. The current Israeli and American governments are betting that Abbas's replacement will maintain the status quo, which allows them to appear supportive of the peace process, at least publicly.

In fact, Abbas has achieved little progress that Palestinians care about. He is also accused of the sort of aggressive tactics associated with Hamas in Gaza—of running the West Bank like a police state, where freedoms of speech and association are ignored. Both parties, say their critics, are essentially exploiting the misery of their people.

Many of the young Palestinians interviewed by Newsweek—from the West Bank, Jerusalem, Israel and Gaza—reject their politicians' self-serving priorities. They're highly educated and heavily underemployed (40 percent of West Bank residents under 30 are jobless). This generation's goals are equality, dignity and freedom: relief from joblessness, housing shortages and censorship, and an end to monitoring by Israeli police and soldiers. Though they are geographically fragmented, social media have enabled them to share information in ways they never could before. A Palestinian in Haifa, in northern Israel, for example, is alerted immediately when Israeli soldiers raid the Kalandia camp in the West Bank.

This has allowed them to unite in mapping a vision for the future. Fadi Quran is a 30-year-old organizer at Avaaz and contributor to Al-Shabaka, a Palestinian policy network based in Ramallah, seat of the Fatah-led government. Rather than the same old paradigms, he says, the conversations are turning to common principles: "freedom, justice and dignity. The problem," he adds, "is that there's nobody articulating a new paradigm. That's the challenge of our generation."

Bethlehem: A Barrier to Rights

Nawawra and his acquaintances at the restaurant agree on one thing: The PA's security coordination with Israel—which includes sharing intelligence about suspected crime and militant attacks and arresting people at Israel's request—constitutes a complicity with a government they regard as their oppressor and reinforces the occupation.

But they disagree sharply on the future role and sustainability of the PA. Nawawra's allegiance stems partly from his boyhood experiences. His father was one of the Palestinian militants who barricaded themselves in the Church of the Nativity in 2002, when the Israeli military was occupying Bethlehem. After the 39-day siege, Nawawra's father went on the run and was eventually killed by Israeli soldiers. The PA took care of his family.

He was 12 then, and like many Palestinian boys who grew up in Bethlehem, he would go on to spend time in an Israeli jail for "participating in violence." Now, he works overnight shifts at a bakery, the only job he can find. With unemployment high, opportunities are greater in Israel or out of the country—in America or Germany. His parents' generation freely interacted with Jewish Israelis on the streets, in markets or on the job, but with the second intifada came the barrier, which encircles East Jerusalem and the West Bank, including Bethlehem. Without a coveted Israeli-military-issued permit, he can't work in Israel, and he can't afford the visa he needs to go abroad. Even though he speaks some Hebrew (learned in jail) the only Israelis he knows are soldiers.

At this point, he's tired of promises and talk. He's nonplussed, too, by right-wing Israeli parliamentary members, like Naftali Bennett, who want to partially annex the West Bank. Annexation, he says, with all its checkpoints, soldiers and tensions with settlers, is not much different from the life he's already living.

But the waiter at the restaurant, who declined to give his name, is impatient for change. He studies law and lives in the nearby

Dheisheh refugee camp, an impoverished maze of crumbling housing. He sees the PA as corrupt and repressive. "God willing it will go, because the people will reach a stage when they will change the authority," he says. "I will support that we go back to Israeli rule, when we only had one enemy: Israel."

Their argument carried on for a while, over pizza, then ended amicably. Before leaving, Nawawra offered the waiter the remainder of his meal. He couldn't take leftovers home, he joked, or others would know he hadn't fasted for Ramadan.

The "Burden" of the Authority

With no Presidential election since 2005, Abbas has been in office for 13 years. Critics say he has hollowed out Palestinian politics, leaving little room for opposition, alternative leadership or generational change. More than two-thirds of Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza want him to resign. Instead, Abbas is accused of digging in and stifling dissent; a new cybercrime law has made it even harder for Palestinians to voice opposition.

Everyone interviewed for this story said elections must happen—even as some, like Nawawra, said they would not vote, given the likely alternatives. Two PA insiders top the list: 68-year-old Mahmoud al-Aloul and 65-year-old Jibril Rajoub, a former head of security forces in the West Bank and now head of the Palestinian Football Association. The third, Majd Faraj, a media-shy, Hebrew-speaking spy chief, is a rumored popular choice among Israelis and Americans. He is not a member of the Fatah's elite Central Committee, which is a constitutional requirement, but his name continues to circulate and a workaround could likely be found.

Nawawra's top choice would be a man he met during his days in prison, the militant turned peace proponent Marwan Barghouti, a former Fatah leader. He is a rare unifier among Palestinians but is serving several life sentences for orchestrating suicide bombings (a charge he denies).

The Fatah-led PA governs 3 million Palestinians in the West Bank, and, according to a recent poll, a majority of those people believe that it "has become a burden." Tight security coordination with Israel is the PA's main selling point internationally. And it has helped keep Israel safe by thwarting Palestinian attacks and crime. But that only adds to resentment, as Palestinians accuse PA security forces of helping to perpetuate occupation by casting a wide net against dissenters, leaving family members and friends victimized and repressed from two sides.

Hanan Ashrawi, 71, one of the few female politicians at the top of Palestinian politics, is advocating for a reformed PLO to take the place of the PA. Her accessibility and sharp English have made her a popular public face of the Palestinian national movement. Still, the younger generation is wary of anyone in the old guard. Ashrawi gets that, and she understands why they've lost faith in the peace process, but she remains opposed to a one-state path.

"Israel is systematically destroying the two-state solution," she tells Newsweek, but "if we start moving towards a de facto one-state solution, what scares me is that we will lose sight of the occupation itself. Israel will be able to continue to expand settlements and create Greater Israel, while we remain in a state of enslavement."

Palestinian pollster Khalil Shikaki says that while there is still a desire for self-determination among young people, the belief is growing that a multinational state "will win out in the end."

If that's true, it means Israeli, U.S. and PA officials are wildly disconnected from a generation of Palestinians.

East Jerusalem: Land of Catch-22

Abbas holds the title of Palestinian leader, but that designation doesn't reflect the disparate makeup of today's populace. Twenty percent of Israel's nearly 9 million citizens are Palestinians, descendants of the families that remained there after the Israeli state's founding in 1948. Another roughly 300,000 Palestinians reside in East Jerusalem, occupied by Israel since 1967.

The Palestinians of East Jerusalem are today denied automatic citizenship. When Israel captured the city in 1967, most believed in the promise of a Palestinian state and refused the offer of citizenship. Decades later—with Israel now talking of a united Jerusalem—they remain stateless. Their continuing disputed status means they can't vote. Furthermore, they must be able to prove their residency or risk losing their legal right to live where they were born—something Israel can revoke if they live outside of Jerusalem for too long or for reasons as vague as not being loyal enough (a new law). Israel argues that they enjoy many of the privileges of residents, such as access to health care, education and jobs. Still, more than two-thirds of East Jerusalemites live in poverty, without the representation that the poor on the west side receive.

Osama Abu Khalaf, 28, is not your typical local; he speaks Hebrew, which Palestinians in East Jerusalem are taught poorly in school. And he has applied for Israeli citizenship, a path Abu Khalaf, and increasing numbers of his peers, believe is the best option for achieving rights.

The process of applying for citizenship is complicated and fraught (for example, Arabic is one of Israel's two official languages, but applicants must speak fluent Hebrew). The lucky ones receive it after a few years' wait. Abu Khalaf applied 10 years ago, when he was 18, and has been repeatedly denied. He is appealing, even as he believes the denial reflects a larger agenda: the Israeli government's desire to maintain a Jewish majority. Israel encourages East Jerusalemites to apply for citizenship, but for much of the past five years it has effectively halted citizenship approvals. The Israeli Population Authority, which handles the applications, denies this charge, blaming severe delays on a backlog (a spokesman would not confirm the number of applicants still pending).

Abu Khalaf doesn't want to live under PA rule, nor does he have faith that the Oslo process was or can be effective. He wants a multinational state; in the short term, he'd be open to a federation of some sort, like Catalonia and Wales. Yet despite his desire for Israeli citizenship and his antipathy for Abbas, he still identifies strongly as Palestinian. There are divisions among his people, but they won't matter in the end. He is convinced Israel will treat all Palestinians the same, for better or worse.

Yasmeen Zahalka, 28, born and raised in Israel, calls herself a Palestinian with Israeli citizenship. The government and media refer to people like her as Arab-Israeli, but she rejects that term because it effectively erases "Palestinian." For decades, she says, her people have been encouraged to assimilate, to become "good Arabs," thankful for their relatively greater rights and comforts. Zahalka, like many of her peers, sees the fates of all Palestinians as linked.

Her father is one of 17 Palestinian members of the Israeli parliament. She grew up in northern Israel, where the Hebrew language and Jewish culture dominate. "It's not just that school doesn't give us knowledge of Palestinian history and culture," she says. "We are also taught something that ignores us and teaches us [only] the Zionist narrative."

It wasn't until she moved to East Jerusalem for work that she became aware of the sorts of tactics that make it challenging for Palestinians to unite. For the first time, she felt the presence of Israel's occupation, including paramilitary police in East Jerusalem neighborhoods. She saw that businesses frequently favor Palestinians with Israeli citizenship over East Jerusalemites when hiring. And that those with citizenship don't want their children to marry Jerusalemites or West Bankers, which would cost them privileges. "It's hard for us to motivate people here," says Zahalka. "We are still divided."

So while she favors one "democratic, secular state built on Palestinian land that's for all the people living in it"—she is unclear on how to get there from here. For Zahalka, the PA is "the enemy," responsible for decades of repression that has put the West Bank to sleep. The existing political parties "need a great deal of work and reform to really represent the people."

Gaza: Despair Over Tomorrow

One thing Palestinians agree on is that young Gazans have it worst of all. The area is imploding after over a decade of war with Israel and authoritarian Hamas rule; among other things, the party (which initially gained support for its social services) represses Palestinian women and harshly persecutes religious and sexual minorities. Hamas rules 1.9 million Palestinians in Gaza, where unemployment is among the worst in the world (approximately 60 percent of young people, two-thirds of the population, are without jobs). That hasn't stopped the party from further crippling Gazans with massive tax hikes, used to fund, among other things, subterranean attack tunnels into Israel. Hamas, say Palestinian critics, prioritizes the death of Israelis over the lives of Gazans.

A big factor contributing to Abbas's lack of popular support is the PA's perceived complicity in perpetuating divisions by crushing the people of Gaza in order to squeeze out Hamas. For example, electricity comes via Israel, but the Fatah-led PA pays for it. Last summer, it cut back payments, leaving Gazans with just four hours of electricity per day, versus eight. And in mid-June, PA security forces shocked and angered Palestinians by violently disrupting a protest in Ramallah against PA sanctions on Gaza.

After occupying Gaza since 1967, Israel formally left in 2005 but retained control of movement in and out. Since 2007, it has tightly controlled access, via land and sea. Israel says the restrictions are necessary to protect against Hamas militants, but they go far beyond what is necessary for security, separating families and making it virtually impossible for students to leave the country to study elsewhere. As a result, the majority of young Palestinians have never traveled outside the coastal enclave.

Hamas does poorly in Gazan polls but has not permitted elections since 2006, so it can't be voted out. And people have little freedom to protest; dissent is often met with brutality. Which leaves young men like Naser (he declined to give his full name to protect his family) with many frustrations. The 28-year-old would love to see a new kind of politics in Gaza—he particularly dislikes the way Hamas exploits religion—but he also has no clear sense of what would replace it. Naser and his friends simply want the territory to open up so they can breathe, think, reassess. If that happened, he says, an alternative politics would be possible, rather than one that benefits only the families of the party. "Hamas and Fatah have their interests," he says. "Their politics are now far from the ideology that they talk about in the media."

America's cuts to UNRWA, which 1 in 3 Gazans rely on, seemed intended to push the PA to meet with the Trump administration. The PA has refused, arguing that the U.S. promotes peace negotiations on Israel's terms. The debates in Washington don't reflect daily realities, says Naser, and the UNRWA cuts only made a solution feel farther away. In addition, the PA reduced the salaries of its employees still in Gaza. Everyone felt the squeeze. "I don't know what's going to happen with the future of the authority," says Naser. "I don't think that it's independent of the [Israeli] occupation. Either we will have a solution or Palestinians will keep dying. We won't give up."

Many in Gaza are considered refugees, the descendants of the 700,000 Palestinians who fled or were expelled from Israel in 1948. On March 30, tens of thousands joined the Great March of Return, intended as a six-week campaign of nonviolent demonstrations; they were demanding the right of Palestinians to return to their homes in what is now Israel. Hamas did not initiate the march, but quickly gave its support (you can't protest for long in Gaza without the party's consent), and by the sixth week it controlled the protests. Israeli officials condemned the march as a front for militants' attacks on Israel.

Naser didn't participate in the protest, but he helped international journalists cover it. The young marchers explained that they joined because they wanted to be heard, and because they believed it might change their future. It was a short-lived hope. Before long, the situation had escalated into the deadliest Israeli-Palestinian conflict since the Gaza War in 2014.

The worst day was May 14. As Israeli and American officials—including Ivanka Trump and Jared Kushner—celebrated the move of the U.S. Embassy to Jerusalem, Israeli snipers shot and killed 60 protesting Palestinians in Gaza. What instigated the shooting is disputed. Critics accused Hamas of using peaceful demonstrations as cover for military operations, which the party has admitted to doing in the past. The result is that, as the violence continued over the next few months,135 people had been killed as of July 6, including two journalists, and more than 15,501 had been injured, with 4,000 young men shot in the legs—a tactic of the Israeli army, to maim rather than kill. Most were unable to receive adequate treatment in Gaza's besieged hospitals.

In Jerusalem, as the Gaza death toll rose, Zahalka joined a Palestinian-led protest close to the new embassy. "We're not in solidarity with Gaza; we are them," she told me at the time. "We are all under the Israeli occupation in different ways."

But Abu Khalaf stayed at his job. The embassy move was irrelevant to him. He also abstained from protests on May 15, for Nakba (Catastrophe) Day, a condemnation of the founding of Israel. He knew they would be met with force.

Nawawra and four childhood friends also sat out the Nakba demonstrations. He used to join protests against Israeli forces, but he stopped after being shot in the leg and abdomen. Still, they hung around a bus stop in Bethlehem, along the graffiti-filled wall dividing the West Bank from Israel, watching as other young men burned tires and threw rocks at Israeli soldiers. They had no better place to be.