The brisk March morning air is a shock after the tourists have recently, regretfully unpacked themselves from their cozy alpaca wool blankets and climate-controlled buses. Watching them is Natividad Sonjo, who has been selling blankets, painted stones and carved bamboo instruments for 15 years on the eastern edge of Sacsayhuamán, an archaeological complex of enormous stone walls and wide lawns just north of Cusco, Peru, the seat of the great Inca empire. The diffuse sunlight of a cloudy morning high in the Andes softly illuminates the city. And then, all at once, the sun breaks through, bringing with it a wallop of heat. Soon, any memory of the cool air has evaporated along with the clouds, but Sonjo doesn't remove the elaborately embroidered wool jacket she put on first thing that morning. "The sun used to warm us," she says, repeating a common refrain among inhabitants of the Peruvian altiplano. "Now it burns us."

The sun has always been strong in Cusco. The city's proximity to the equator and its altitude—some 11,150 feet above sea level—mean that come summer in the Southern Hemisphere, sunlight doesn't have to travel far to reach Cusco. It also doesn't encounter much interference along the way—not a good state of affairs for those who live here. The amount of ultraviolet radiation that makes it to Earth is limited by atmospheric ozone, a molecule made up of three oxygen atoms bound together. At higher altitudes, there are fewer ozone molecules between the Earth and the sun, making UV readings normally elevated in mountainous regions near the equator. In 2006, climate researchers found Cusco and the surrounding area to have the highest UV readings in the world. But now, as climate scientists say the planet is reaching critical temperatures worldwide, Peruvian meteorologists are recording record levels of UV radiation throughout the country, while meteorologists in Chile, Argentina and Bolivia are recording similarly increased levels in regions close to Peru.

The effects of prolonged exposure to ultraviolet radiation can be calamitous. The risk of developing skin cancer doubles after only a few acute exposures, say dermatological researchers, while repeated exposure can cause cataracts and permanent eye damage. The planet is affected too: Increased UV can limit photosynthesis in crops and raise the temperature of the uppermost layer of the ocean, killing off the phytoplankton that are a key source of nutrition in the ocean's food chain.

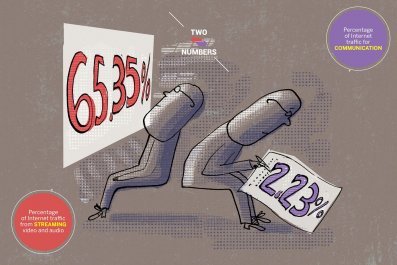

As the Peruvian meteorological agency's chief UV researcher, Orlando Ccora is responsible for collecting the data from a network of nine spectrophotometers dotted throughout the country's varied landscape. The data show that cities up and down Peru's Pacific coast, including Lima, the capital, have regularly recorded daily UV index readings of over 14 during the past two months, while in the southern Andes region, one in every four days has had a reading of 16. For comparison, the highest UV index reading in Miami last year was roughly 12.5, and the World Health Organization regards any reading over 11 as "extreme." In January, Ccora's team recorded an average UV index reading of 13.6 for Cusco—the highest average monthly reading since they began collecting data in 2009.

Scientists have been concerned about serious reductions in ozone since at least the 1970s, says Paul Newman, chief scientist for atmospheric sciences at NASA. He explains that man-made chemicals like chlorofluorocarbons—which were used in refrigerants, propellants and aerosols from the 1970s into the early 2000s—collect over Antarctica during the Northern Hemisphere's summer months. Then, when the Southern Hemisphere begins to warm in August, the CFCs get activated by sunlight and start to destroy the ozone molecules that trap and deflect enough UV radiation to allow life to grow on Earth. By November, that depleted-ozone air spreads out through the Southern Hemisphere.

"Think about looking down on a bucket of white paint," says Newman. "If you put a dollop of red paint right at the center of that bucket and start stirring the whole paint bucket, the whole bucket turns pink. That is, the depleted region, as you mix it into the mid-latitudes, lowers ozone everywhere. And this last year, there was a pretty big ozone hole. It persisted for a long time." NASA data show that the greatest ozone-depleted area in the world besides the one over Antarctica runs along the Peruvian Andes from Ecuador and into Chile and Bolivia.

The United Nations worked to phase out the production of CFCs under the Montreal Protocol of 1987, but many CFCs already in the atmosphere have long life spans—sometimes up to 100 years. "So right now, we're at a time of peak vulnerability," says Newman. "All of these gases come out of the atmosphere very slowly. There are hints that it's getting better, but we're not 100 percent confident that we're really seeing a decline."

A further contribution to increased UV levels this year, say Ccora and others, is the heavy El Niño phenomenon currently being felt along the tropical Pacific coast. In an El Niño year, strong, warm winds blow in from the west, disrupting normal weather patterns. Late last year, El Niño–linked rains caused massive flooding in Argentina, Paraguay, Uruguay and Brazil. According to Ccora, at least some of those rain clouds had been pushed across the continent from the southern Andes, where it normally rains steadily from November through April. That lack of cloud cover over southern Peru means that even more UV is reaching the Earth's surface there than normal. "We're experiencing a drought in the southern Sierra and heavy rains in the central and northern regions of the country," Ccora says. "This season, no region is safe." In early March, flooding displaced thousands and killed at least five people in central Peru.

Back at the Sacsayhuamán ruins, Sonjo's friend and fellow vendor Lucinda Fuentes was worried about the drought—among the worst she'd seen. "It's terrible, because in May and June there won't even be any clouds in the morning," she says. "Year by year, the drought and the sun are getting worse." Fuentes, Sonjo and the 12 other vendors at the archaeological site complained of a long list of ailments brought on by the sun. Freckles that got bigger until they had to be removed, rashes that burned and itched at night, conjunctivitis and even cataracts. Jessica Almanza, a tour guide with the Peruvian Ministry of Culture, says she burns even when it does rain. Thick stone walls, tile roofs and narrow streets make dodging the sun within Cusco's city limits quite a bit easier, but as so much of the local economy relies on agriculture, mining and tourism, an overwhelming proportion of the population will spend, by necessity, a potentially harmful amount of time in direct sunlight.

One of the few Peruvian cities trying to comprehensively grapple with UV exposure is Arequipa, almost 300 miles south of Cusco. Arequipa recorded an average UV index reading of 12.5 in 2015. There, public health campaigns encourage the use of wide-brimmed hats, while schools and businesses are required to stretch green webbing over exposed courtyards and lawns. But the lack of a single nationwide public health campaign means Peruvians elsewhere are forced to adapt creatively. In Lima, for example, bus fare collectors stand under enormous umbrellas, and the ghostly white tinge of a sunscreen-lathered face on the morning commute is becoming more and more common.

Jhon Valencia, a private tour operator in Cusco, sighed when asked how he has adapted to the stronger sun. "There comes a time in a man's life when he must put on long-sleeved shirts and wide-brimmed hats, even if he doesn't want to," he says. Diana Morocco, a Cusco resident eating lunch near Quri Kancha, the famed Inca temple built in homage to Inti, the all-powerful sun god, says she puts on SPF 100 sunscreen twice daily. "We spend all day in this terrible heat," she says.

In late January, the World Meteorological Organization said El Niño and man-made climate change had combined in 2015 to raise global temperatures an additional 1 degree Celsius over the Earth's pre-industrial temperature—enough of a shift, the majority of climatologists believe, to have catastrophic effects in the future. "The power of El Niño will fade in the coming months," said the secretary-general of WMO, Petteri Taalas, in a statement. "But the impacts of human-induced climate change will be with us for many decades."

But while Ccora's work with the meteorological service means he spends much of his day looking at numbers and projecting into the future, ultimately he is concerned with educating the public so people can take steps to protect themselves from a world that has already become more hostile. "Ten years ago, people here in Peru didn't know much about UV radiation," says Ccora. "Now many more do, but there is still that proportion of the public that doesn't know how dangerous it can be. We've got a lot left to do."