My earliest memory of my grandad was when I was six years old. It was Christmas day, and he came into my parents' house and yelled "grandson!" loud and proud with his thick Jamaican accent.

Every time he said the word, I felt a warmth and love from him that I couldn't explain.

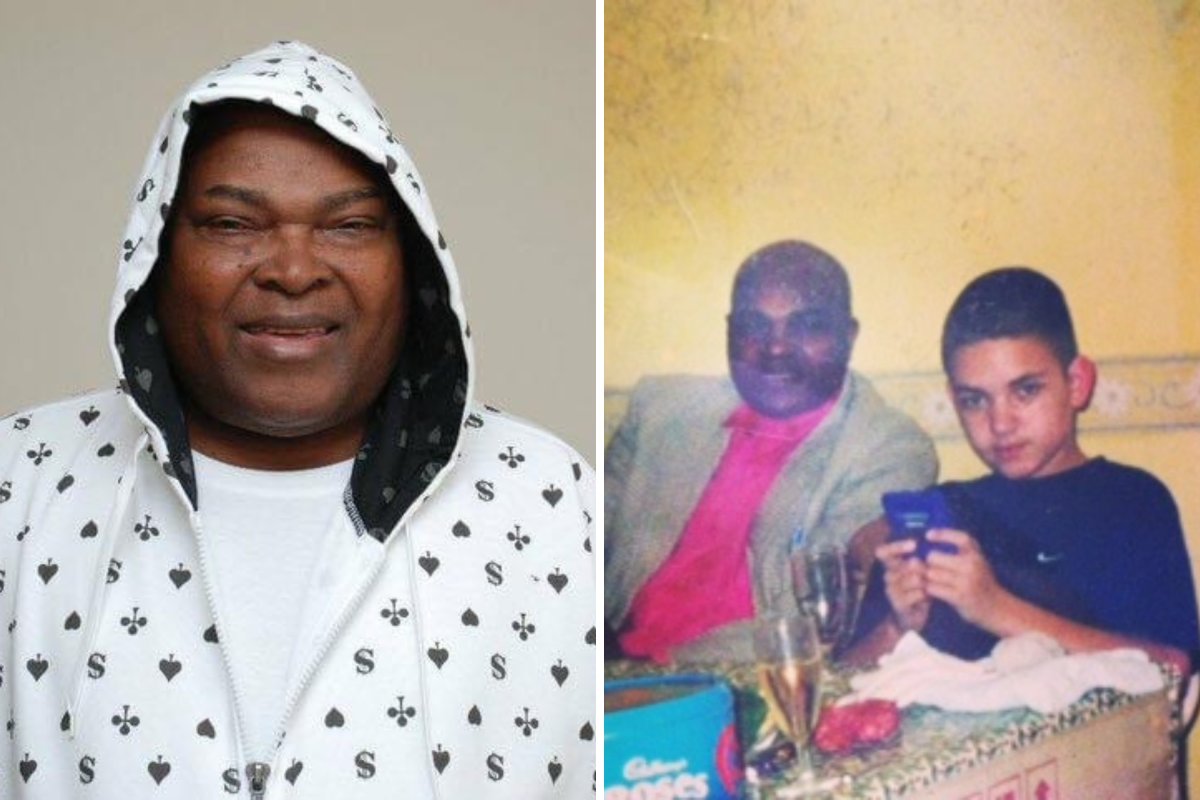

My grandad, Robbie "Emmanuel" Robinson was born in St. Elizabeth, Jamaica on October 15, 1939, and came to the U.K. at 21 years old in the 1960s.

Brought up in a Jamaican and British household with my mom, dad, and brother, my grandma taught my mom how to cook traditional Jamaican food and she learned from the best cook in our family—grandad.

I remember going to his one day for sardines and rice, which would ordinarily be a bland dish, but he made it taste like the best thing since sliced bread. Old school Jamaicans have a special way of seasoning food that can make anything taste good.

By trade, grandad was a cab driver and, by passion, a talented musician. He made jazz and reggae music and regularly traveled across Europe to perform in the 1980s. He wasn't widely known but did release several albums. He loved music and he loved people, something my mom always says—as well as being loud—I got from him.

Being loud didn't help me when it came to school. I was quickly labeled a "bad breed" by teachers. Turns out my personality wasn't the only reason why some teachers didn't like me—my friends and I received racism from teachers. The worst thing is, no one believed me when I said it.

As a young person, I never felt like my voice was valued by adults. This played a pivotal role in what I would do with my life in the future. Growing up in South London, England, in the early 2000s, you had to carry yourself a certain way to survive.

At the time, the things I saw and did seemed normal, but looking back on my teenage years it was a traumatic but exciting time. I was constantly being tested and doing stupidness on the street, and if it wasn't for my dad and grandad, I don't know where I would have ended up.

I was one of a few boys I knew who grew up with their Black dad in their household. My dad was an example to me of what a man is meant to be. A provider, a protector. He worked seven days a week for the benefit of his family and never complained. I can't express how important it was to see that being modeled every day in my house.

In my late teens, I began to write music and DJ, but I still felt lost. I continued to hang around out on the streets until my early 20s. That's when I really understood what Alzheimer's disease was for the first time.

My grandma had been diagnosed with it when I was 18 years old, but it wasn't until I was 20 that I saw its true effects. I went to visit my grandparents one day and when I arrived my grandma was speaking incoherently and stomping around the house.

She then went into the kitchen and began to use the kitchen floor as a toilet. It crushed me. Not just the thought of my grandma being a shell of herself but the sadness I saw in my grandad's eyes.

My grandad was always full of energy and could light up any room, but this was the first time I saw him depressed and quiet.

In his early 70s, grandad became grandma's full-time carer while being dangerously overweight, having high blood pressure, arthritis, and diabetes. It was taking its toll on him physically and mentally.

I decided to visit more regularly and help where I could. Cleaning and doing shopping for my grandparents never felt like enough for me but I think grandad appreciated the conversations we had more than anything. Grandma could no longer hold a coherent conversation.

I always wanted to make music with my grandad, but by the time I got into it, he had to stop due to ill health. I knew that grandad had music laying around that he had never used before, so I asked him to send me all his beats.

From there, I decided to create my first album. I used my grandad's music to pay homage to him while raising money and awareness for people who have Alzheimer's.

I found the biggest Alzheimer's charity and contacted them to ask if I could use their logo on my album so that people knew I was officially supporting the charity. They agreed and that's when I started to put together the album. I was 22 years old at this point and had found my purpose "to bring light to this dark world"—and my vehicle was music.

At the beginning of 2013, when I was 25 years old, I watched the movie Inception, which changed my life forever. Watching that inspired me to write a spoken word piece called Digital Slaves. This was the first poem I ever wrote, and I did so unintentionally. In fact, it wasn't until I performed Digital Slaves at an open mic that I realized it was even a poem.

After the performance, a guy came up to me and said "You're a sick poet" which I didn't know how to take at first because I used to view poetry as corny. I quickly saw the power of poetry when I continued to perform Digital Slaves.

When I showed the poem to my grandad, he said: "This is a new approach, grandson. It's unique." From that moment, I knew it was special.

Poetry gave me the voice I never had as a teenager in school, with poetry, people had to listen to me. That's where the idea for my charity, Poetic Unity, came about.

In 2014 I saw how spoken word poetry could help young people feel heard and valued in society, especially those who are marginalised. I was coming to the end of my time volunteering for Alzheimer's Society.

I was beginning to put the idea of Poetic Unity together when on July 7, 2014, I got a call from my mom, telling me that my grandad had passed away.

I felt helpless and an overwhelming sadness. This man, this giant, this king who I idolized is gone and I never got to say goodbye. That's the thing that still hurts me to this day.

We never got to share one more rum together, we never got to reason again over music or laugh about his times in Jamaica as a youth. My grandad never got to see what I built with Poetic Unity, but he helped build the foundations.

My grandad helped me find my purpose, my grandad passed on the creative gene to me, and I believe my grandad spiritually introduced me to my wife, who I met three months after he died.

This year marks 10 years since the sudden passing of Grandad, and it's 12 years since he produced my first music album "Paying Homage to the King", which made thousands for the Alzheimer's Society charity.

As a mixed-race working-class boy from Brixton, London I could never have imagined running my own charity that supports thousands of young people every year, and this achievement and the position I'm in now is largely down to my grandad.

The belief he had in me, the unique bond we shared, and the confidence he gave me saved my life.

Ryan J. Matthews-Robinson also known as Ragz-CV is a poet and the Founder and CEO of Brixton-based charity, Poetic Unity, which provides support and services for thousands of young people across the UK.

All views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Do you have a unique experience or personal story to share? Email the My Turn team at myturn@newsweek.com.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.