Compiled by Associate Editor Tim Baker

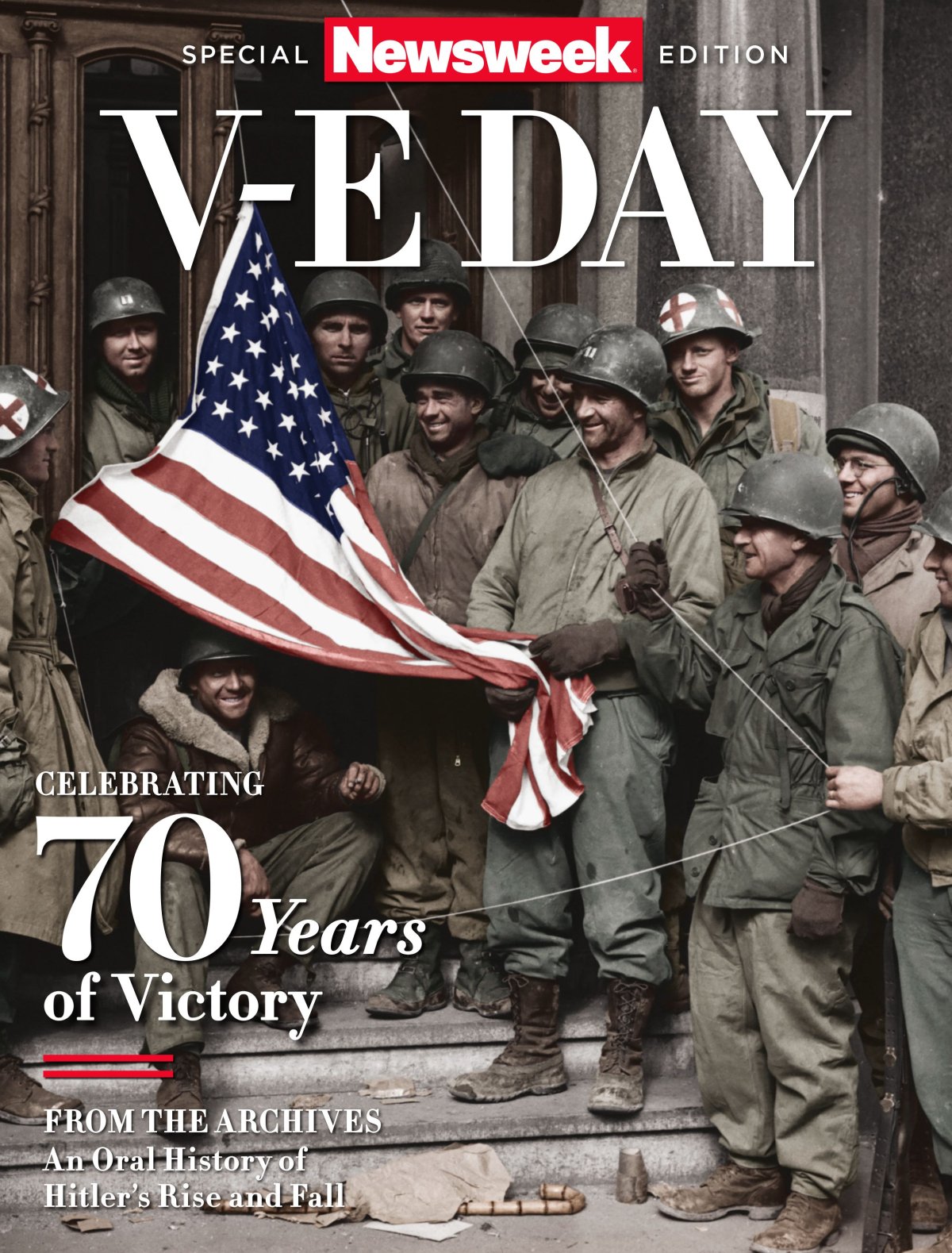

V-E Day, or Victory in Europe Day, was first celebrated on May 8, 1945 and marks the end of World War II in Europe. Seventy years later, the Veteran's History Project at the Library of Congress preserves firsthand accounts of soldiers that, like these, show the full scope of the wartime experience.

We had a sad experience two days after our first mission. We were ready to go on a second mission but got information that the target was overcast, and they scrubbed the mission. So we went back to the barracks to get a little extra sleep, and they woke us up saying we were going on a practice mission out over the North Sea. They called it "radar flights," where you could see through the clouds, and that was something new for us. As we got ready to take off, we found out we didn't have any guns on the plane. We were flying around over England, and there were about 120 planes up that day in formation doing the practice radar missions. Because we didn't have any guns, the pilot said, "If you guys want to, you can sit up in the radio room because it's warmer up there; and you won't get so cold." As we were sitting there trying to stay warm, we heard over the intercom that we were being attacked by Me-109 fighters, but we couldn't do anything because we didn't have any guns. One plane hit the No. 3 engine, and it set on fire. The fuselage right above our heads ripped apart. The plane was on fire, and the pilot told us to bail. So we were all over the North Sea, and it just happened there was a squadron of British Motor Torpedo Boats on their way to raid German shipping that night. There were six of them, and they had seen the hit and the parachutes come out. So Lt. Cmdr. Bradford from the British Navy picked up five of us alive, one who had drowned, and one who had hit his head on the bomb bay doors and was almost decapitated. Three of them they never found. So five out of 10 of us were still living. And I was the last one to get picked up. They almost left without me, but then he heard me hollering; it's good to have a big mouth once in a while.

—Bruce E. Alshouse, Tech. Sgt. in the Army Air Corps. As a tail gunner on a B-17, he flew more than 25 missions.

It was evening, and as nine o'clock brought lights out, I found myself crying. I wanted to go home; I was homesick. I had never been away from home. When I say I cried, I cried all night. Some of the older fellas said, "Look, son. You can't get out and can't go home. You're in the Navy now." They said, "We'll take care of you. Don't worry, tomorrow will be a different day."

—Gilbert Arbiso Jr., Navy crew member on the Battleship U.S.S. South Dakota, on his first emotions after shipping out with the Navy

I felt like just refusing to go on, but, of course, you always go on. It has nothing to do with being brave. It's just simpler to go on. The general casually turned to the captain: "It's not too torn up, is it?" "No, sir." "The Rhine can't be far ahead." The general acted as if it was something special, the kind of thing you went out of your way to see. When we got to the Rhine and stopped to gaze at the little flashes of light from the guns at Mannheim, the trivial sounds of war carried across the neutral gray water…. There at the Rhine, I felt the way you do when your football team loses the game in the last few seconds. There at the Rhine, I felt drained and no longer afraid. There at the Rhine, I felt that I couldn't bear to look at the general as if he were some friend who had said or done some embarrassing thing. With unconcern, I listened to the dismal, far boom of fieldpieces, the thin cracking of rifles, and then we retired from the naked shore.

—William Bache, Cpl. in the 409th Regiment of the 103rd Division of the U.S. Army during the invasion of Europe. He wrote the WWII memoir On the Road to Innsbruck and Back in 2001.

When we were going up into Belgium, it was getting to be colder weather, and everybody was sleeping in the pup tents. A civilian came from his village and said, "I'd like a couple guys to come and sleep in my house where it's warm tonight." So my closest buddy and I went down there and slept in a loft with a feather bed. Boy we sunk down in that, and while we were there, they washed all our clothes and had 'em laying out on a chair the next morning. They were thankful that they'd been liberated and that they were free...they couldn't do enough for the GIs going through there, and that happened through all of the towns that we went through. People would come out and wave at you and bring out the wine...I was just one little spoke in the wheel of the war.

—Jay S. Adams, Pvt. in the 37th Engineer's Battalion of the U.S. Army, explaining civilian hospitality he encountered in Belgium

In September 1944, I was transferred to a troop carrier squadron in France flying C-46 cargo planes. My first mission with the new outfit was to fly ammunition into Germany, so we flew to England and picked up the ammunition. I checked the loading and found that we were 10,000 pounds overloaded. While flying past the city of Paris, we lost oil pressure to the right engine and attempted to land at Charleroi, Belgium, but the pilot overshot the runway. When we tried to circle back for another attempt, we lost altitude and flew into a two story house. I was knocked out, and when I came to, I heard someone crying in another part of the house. The ammunition was exploding, and timbers were falling, and there was rubble all over the place. I attempted to locate the person, but I couldn't find anyone. I walked down the rubble to the ground in an attempt to go around to the front of the building, but I was stopped by a Belgian man who held me there until the ambulance jeep arrived and took me to the hospital.

I was covered with scrapes, lesions and had to get a lot of stitches. While in the hospital, my old Commanding Officer came over from England and told me that I was being transferred back to my old unit, and that we were all going back to the States. I found out that I was the only crew member to survive, and the person that was crying was a woman with a broken pelvis. We were the first troop ship to enter New York Harbor on May 10, 1945, two days after V-E Day.

—Homer Anderson, First Lt. in the 316th Troop Carrier Group of the Air Force, on how he finally got home

This article appears in the Newsweek's special edition, V-E Day, by Issue Editor Tim Baker of Topix Media Lab.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.