The below is an excerpt from Truth: A Brief History of Total Bullsh*t by Tom Phillips.

Stalin's Soviet Union might not immediately seem like an ideal place to earn a living as a con artist, and, indeed, if you judge Vladimir Gromov's life by petty metrics like whether he was sentenced to death at the age of thirty-six, then he might have been wiser to seek an alternative profession.

On the other hand, if you judge it by whether he managed to get his death sentence commuted by writing a play about a love affair between a Bolshevik man and a beautiful capitalist woman half his age, which he sent to the deputy procurator-general of the USSR, then things look a bit rosier for Gromov.

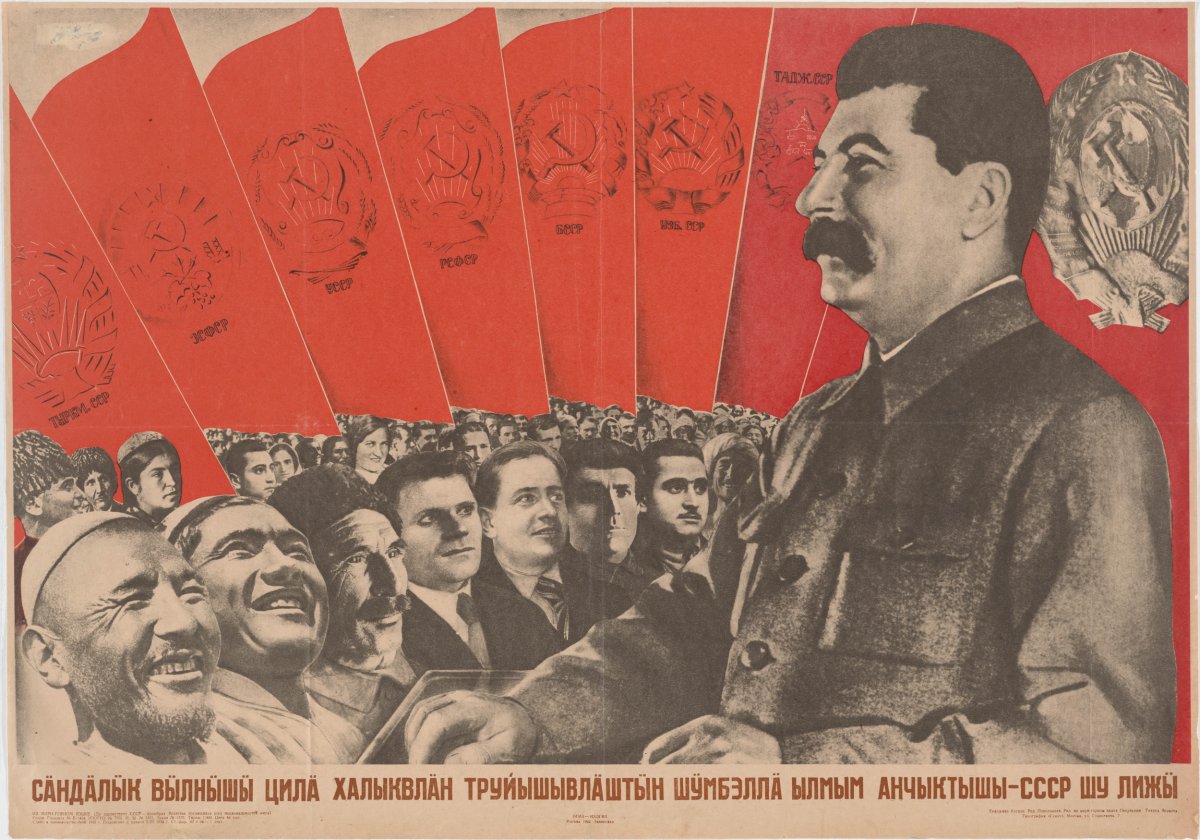

Gromov's insight was that the climate of fear, oppressive bureaucracy and ideological rigidity of the early Stalin years was in fact ripe for exploitation—which he managed to do in spades, appearing in a wide variety of guises as an expert engineer or an acclaimed architect, amassing a small fortune along the way. He realized that the Soviet bureaucracy's unquenchable hunger for documentation left the system with very little capacity to actually check the validity of the reams of paper they were accumulating.

So instead of trying to fly under the radar, he opted to flood the system, stealing or forging documents with wild abandon to enable him to hop between "jobs."

Any questions he might face could be deflected with the proper appeals to Bolshevik dogma, and, once he had persuaded somebody to accept his identity, he exploited the intimidating power of status under Stalin to ensure that nobody else would question him—a perfect bullshit feedback loop, enforced by the very authoritarian culture that was supposed to stamp out transgression.

In the words of the historian Golfo Alexopoulos, "He did not avoid the authorities but bombarded them with false employment papers, phony requests for money and goods, and vicious denunciations." His standard modus operandi was to establish phony credentials with the help of fake documents and to use that to get himself an appointment to a senior role in a state industry—ideally one in a far-flung location somewhere in the Soviet empire. He would obviously need his wages advanced and his travel expenses paid up front. By the time the coal mine in Vladivostok realized that their chief engineer had never turned up, Gromov would be somewhere else, already starting on a new "job."

The crowning achievement of Gromov's scamming came when he managed to get himself appointed to the exalted role of engineer-architect for a major new fish cannery near the Kazakhstan-China border.

Now, this might not immediately strike you as the world's most glamorous assignment, but in the Soviet Union in the 1930s, it was a really big deal. So much so that Gromov managed to persuade the commissar of supply, Anastas Mikoian, to send him the vast sum of one million rubles, through the cunning technique of asking for two million rubles. (To give you a sense of how much that was, the average yearly salary at the time was just over 1,500 rubles.) The Kazakh cannery was the peak of his career, but, unfortunately for Gromov, it was also where his downfall occurred.

That's because he made the classic mistake of abandoning his tried-and-trusted methods—namely, the method of bolting before anybody sniffed him out. This time, Gromov felt that he was onto such a good thing that he decided to stay on the ride and fully embrace his false identity as an engineer-architect. Possibly, he just wanted to put down some roots and actually become the person he was pretending to be. Maybe the power and money went to his head.

Alexopoulos suggests that "perhaps Gromov ceased to be an imposter by 1934, not because he had internalized or come to believe his own lies, but because he viewed those around him at Glavryba's monumental construction project as essentially no different from himself."

In other words, if everybody else was faking it, why shouldn't he? But this desire to settle down into his newfound status couldn't actually survive too much contact with the harsh reality that, bluntly, he didn't actually have many skills in the fields of engineering, architecture or fish canning.

Gromov's tactics of denouncing anybody who questioned him as an enemy of Stalinism were effective in the short-term, when he was constantly on the move...but, after too long in one place, they merely built up a critical mass of people with an enormous grudge against him. But even after his arrest and death sentence, he still managed to escape, one last time, turning the creative energies that had fueled his production of imaginary work orders, invoices and telegrams into a more traditional form of fiction.

His prison-produced play, titled Love and Motherland, may not have been terribly good. In fact, when the procurators passed it on to the head of the playwrights' union for a professional opinion of Gromov's literary merits, it received the kind of critical notice that would terrify any author, never mind one who was relying on a single manuscript to save him from execution. The union man wrote that Gromov's "playwriting ability is extremely low" and that "the work has no ideological or artistic value and is clearly unacceptable from any standpoint."

I think it's fairly safe to say that John Keats would not have coped well with a review like that. And yet, miraculously, it worked. Gromov's death sentence was commuted to ten years of labor. To this day, it remains unclear exactly what could possibly have convinced a senior Soviet official to spare Gromov's life simply on the basis of a play depicting a senior Soviet official as a handsome and heroic figure who bones a hot twenty-three-year-old Parisian woman and converts her to socialism through the power of his ideological and sexual magnetism.

Ah, well—I guess that will just have to remain as one of those inscrutable historical mysteries we will never solve.

Views expressed are the author's own.

Excerpted from Truth: A Brief History of Total Bullsh*t by Tom Phillips © 2020 by Tom Phillips, used with permission by Hanover Square Press/HarperCollins.

Tom Phillips is a journalist and writer based in London. He was the editorial director of BuzzFeed U.K. and is now editor at FullFact, the UK's independent factchecking charity.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.