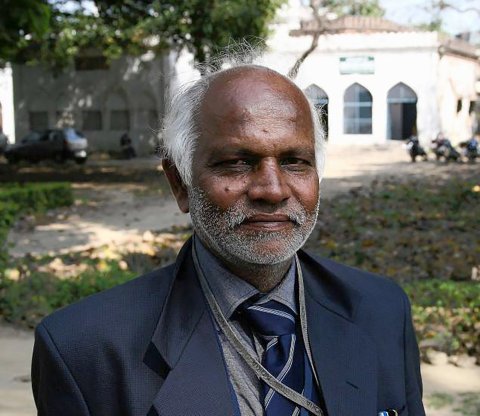

When a gay professor at one of India's most prestigious universities was found dead two months after vigilantes barged into his house with a video camera and caught him in a naked tryst with a bicycle rickshaw driver, police concluded it was suicide. He had been suspended from his teaching duties for "immoral sexual activity" and publicly outed in a society deeply prejudiced against gay people, and there was poison in his blood.

But activists and former colleagues of Shrinivas Ramchandra Siras, a professor of Indian literature at Aligarh Muslim University in the northern Indian state of Uttar Pradesh, are puzzled by a few odd details of his death—his cellphone was missing, his ATM card was used either just before or just after his death, and while the room where his body was found was locked from the inside, the front door of the house was bolted and padlocked on the outside. What's more, he had just been reinstated at the university by virtue of a court order, and he had found friendship and support among those fighting for gay rights in India.

Even if the official explanation of suicide is correct, the more than five-year-old case has become one of the most prominent tests of India's official and unofficial intolerance of homosexuality in recent years. And while the Indian legal system failed Siras, his story may wind up doing more for gay rights than India's usually liberal courts. For that, thank Bollywood.

There's no singing and dancing in Aligarh, the new movie based on the professor's life and death. India's film industry is generally as homophobic as its movies are camp, but director Hansal Mehta has made in Aligarh what the British Film Institute called "probably the best film yet on the Indian gay male experience." The presence of veteran tough guy Manoj Bajpai in the lead role has ensured that it's not going to sink into film festival oblivion. And if it gets past India's conservative censors, a wide-scale urban theatrical release is slated for February. That would be a bold move in a country where thugs vandalized theaters and beat up a cinema manager in 1998 to protest a film that depicted a lesbian romance.

Citing a renewed public debate in India on homosexuality, Mehta says, "I would like to believe that [Aligarh] is already having an impact."

'Aren't You Ashamed?'

Professor Siras was outed and suspended from his job in February 2010, says author and gay rights activist Saleem Kidwai, during a "wonderful little interregnum" when homosexuality was legal in India. In July 2009, the Delhi High Court had struck down as unconstitutional a colonial-era anti-sodomy law, though religious groups quickly filed appeals. Known as Section 377, the law made gay sex a crime punishable with up to 10 years in prison, and in 2013 India's normally progressive Supreme Court reinstated it.

Consensual gay sex that takes place in private in India is rarely prosecuted, but gay people are frequently persecuted. With landlords liable to evict gay tenants and families quick to disown gay relatives, blackmail is common. Cops routinely demand bribes or sexual favors from men caught cruising, and at several universities gay students face expulsion from dormitories and even from school.

Until Siras was outed, he was practically invisible. Like many closeted gay men in India, he was married, but separated, with divorce proceedings underway. It appears he had few close friends. The subject he taught was unpopular, so he had few students. Though he'd won a national award for his poetry, none of his colleagues could read the language in which he'd written it.

Aligarh Muslim University spokesman Rahat Abrar showed me the video that made Siras the focus of a national scandal on his desktop PC. From the first blurry frame, watching the video feels wrong. The camera wobbles as the screen shows a bright peephole in the center of a black screen, the cameraman apparently tilting a handheld rig from left to right. He's angling the lens to get a better view through a hole in the door—the kind of peephole many people have in their front door to let them see a visitor without opening it. A muted conversation is just audible from the other side, a murmur. Siras lies supine on a sofa in his living room while another man, seated in a chair, appears to stroke his forehead.

A moment later, the scene cuts to inside the room—it's not clear how the men gained access to the room. The handheld rig steadies on Siras as he briskly stands up. He is naked. The other man—later identified in media reports as "a rickshaw puller"—is wearing a shirt but no pants. "What's happening? Who are you?" Siras asks the camera crew in Hindi. "He invited me here," the other man says in a defensive tone.

With his white horseshoe of hair, prominent paunch, spindly legs and crooked teeth, Siras is a pathetic figure. He looks lost, guilty, too desperate to be angry. It's painful to watch. Two or three minutes pass before he wraps a sarong-like garment around his waist, while the camera crew fire questions at him. Not once does he say, "Get the hell out of my house!"

"My name is Dr. S.R. Siras," he tells them, as if he has to explain his presence in his own apartment. "I am the chairman of the modern languages department." The camera zooms in on his university identity card, which someone has propped on a table, then on a similarly displayed unopened Nirodh-brand condom. In accented English, a sententious voice intones, "Sting operation." There is another cut. Now Siras, wearing a shirt, is seated on the couch. The cameraman holds a cellphone in the frame as he calls another university professor. "We found your colleague naked, engaged in homo-sex," a voice says. "What do you have to say about him?" Otherwise speaking in Hindi, he says "homo-sex" in English, as a single word.

"Aren't you ashamed of yourself?" the same voice asks Siras. There is no answer. "Aren't you ashamed?" the unseen man says again.

"Yes, I am ashamed," Siras says numbly.

How the men with the camera knew to go to Siras's home at that particular time, or that the one-way lens of the peephole in his door had been removed so they could film through it, remains a mystery. The more chilling mystery is what happened after their camera was switched off.

Abrar maintains that Siras phoned another faculty member to ask for help while the camera crew was still in his apartment, whereupon Abrar and several other university officials rushed to the scene, pleaded with the film crew not to release the footage and called a doctor to examine Siras, because he seemed extremely agitated. The following day, the university vice chancellor suspended him from teaching, replaced him as department chairman and kicked him out of faculty housing for "immoral sexual activity." But on the evening in question, Abrar insists, "We went there only to help Dr. Siras."

Siras was initially reluctant to take any action against the camera crew, who he said had barged into his home, or the university. However, once he was persuaded by friends a week or so later to fight back, he told a very different version of that "sting," according to allies who discussed the matter with him at the time, as well as court petitions and police papers filed by him or on his behalf. In a petition filed against his suspension with the Allahabad High Court, for example, Siras says he was "extremely shocked and surprised" to see Abrar and two other officials join the camera team in his apartment because he had neither "called any of them for any help nor had he invited any of them to his house."

"Siras did hint that [the camera crew] might have been working on the behest of the administration," says philosophy professor Tariq Islam, who was instrumental in convincing Siras to fight back and contacted gay rights organizations on his behalf.

Abrar denies that any university official had knowledge of the sting operation, and says police exonerated him and the other officials named in the professor's complaint. He also says the rickshaw driver admitted to receiving money from Siras, so his suspension for "immoral sexual activity" was justified.

Two months after the incident, on April 1, 2010, the Allahabad High Court issued a stay on Siras's suspension. The judges ordered the university to allow Siras back into his apartment and barred the media from posting the "sting" video. They also noted in a written ruling that Siras's lawyer had "a point in submitting that sexual preference of an adult may not amount to misconduct," especially when that preference had only been discovered through a violation of his privacy.

Siras apparently never read the ruling. When his friend, Indian Express reporter Deepu Edmond, spoke to him April 5, Siras was back on campus, waiting for a written copy of the judgment so that he could reclaim his post as department chairman. But on the evening of April 7, he was found dead in an apartment he had rented after being kicked out of university housing.

There was no suicide note or bottle of pills or poison beside his body, which was "covered in maggots" by the time he was discovered, medical examiners told reporters. The TV remote was right beside him, as if he'd been channel surfing. His mobile phone was missing, and someone had withdrawn $300 with his ATM card around the time he is estimated to have died. A preliminary medical report indicated traces of poison in his body—enough for the local superintendent of police to say categorically, "His death was not due to natural causes.... There were blue spots on the body; his nails were blue." A later report, however, indicated doubts about the presence of poison, so the cause of death remains uncertain. And then there was the detail worthy of Agatha Christie—the door of the room locked from the inside, but the front door padlocked from the outside. Later, it was suggested that Siras had come out from a rear entrance and padlocked the front door to avoid unwanted media attention, according to a colleague.

None of that amounts to much more than masala (or "spice"), as the Indians say, and Kidwai, the activist, says the investigation into his death fizzled out because his estranged wife and other relatives were not interested in pursuing the matter. "After he was dead, you had to be next of kin to pursue the case."

Siras's friends still question why he would have killed himself. Long isolated by his secret, he had confronted the worst—being outed—and begun to find acceptance from sympathetic colleagues and the LGBT activist community, they say. He seemed happy, even triumphant, says business administration professor Naved Khan: "The last time we met him, he was very upbeat."

According to Edmond, the last person known to have spoken with him, Siras was talking optimistically about becoming a gay rights activist or moving to America to teach Marathi—a language spoken in western India. Even so, Edmond says the most likely explanation is suicide.

After the professor's death, two of the three people Siras accused of making the film were arrested on charges of criminal intimidation, breach of privacy, trespassing and blackmail, though there was no indication in the court documents Siras filed that they had demanded money. However, they were soon released, and the case has gone nowhere. The same court that stayed the professor's suspension ordered local police not to arrest Abrar and the other university officials named in Siras's privacy complaint without additional evidence.

'Homosexuality Is a Disease'

Progress on gay rights in India has been slow, but there has been some movement recently: Finance Minister Arun Jaitley spoke out against the Supreme Court's handling of the anti-sodomy law, and in December opposition member of Parliament Shashi Tharoor introduced an amendment to decriminalize sexual intercourse between consenting adults, regardless of gender. Like most bills introduced by the opposition, it was defeated, but Tharoor, a former U.N. official, has vowed to reintroduce it in the next session.

Still, opinion polls such as a 2014 survey by the Pew Research Center show that around two-thirds of Indians view homosexuality as immoral (the same percentage thinks premarital sex is wrong). As recently as 2009, almost as many believed homosexuality to be a disease, according to one poll. While India's National Crime Records Bureau doesn't track homophobic crimes, sexuality rights activist Gautam Bhan says there is a lot of anecdotal evidence of familial violence to enforce gender norms or force gays and lesbians into arranged marriages, as well as school bullying and reports of police beatings and harassment. Suicide is common in such cases.

Bajpai, who plays the character in Aligarh based on Siras, is best known for his turns as macho psychopaths in operatic Bollywood gangster sagas. At the Busan International Film Festival this past October, where Aligarh premiered, his performance received a standing ovation.

To have a broader impact in India, Aligarh will have to get past censors who recently ordered the kissing scenes between Daniel Craig and his female co-stars in the latest James Bond film, Spectre, snipped because they were deemed too long for delicate Indian eyes. There's every chance that conservatives, either Hindu or Muslim, may try to keep Aligarh out of Indian theaters. And Aligarh Muslim University may seek to block it on legal grounds, though Abrar, the university public relations officer, says he could not know what action the university might take until officials have seen the film. "I have not seen the movie, but I condemn it. They never contacted us," he says, explaining that the film was shot at another college campus without the university's knowledge.

Bajpai says he immersed himself in the Marathi poetry Siras loved to get closer to the character. "One thing I'm very sure of is that whoever is going to see the film will be touched," he says. "This is the force that this character leaves behind."

Aligarh director Mehta says his film does not seek to solve the mystery of the professor's death, but rather to explain the mystery of his life. "It's a film about loneliness and old age and a society that does not let you exercise the choices that a democracy is supposed to give you."