Late last August, just 50 miles south of Washington, D.C., a series of explosions rocked the normally placid Potomac River. The blasts came from artillery belonging to the USS Dahlgren, which was testing a new targeting system. Using a drone to observe its marks, the targeting system automatically recalculated its aim and retrained the Dahlgren's gunners. The following volley hit, clearly demonstrating the value of the targeting system. But perhaps more impressive was the USS Dahlgren itself, which, despite its name, isn't a ship.

The Navy sometimes refers to the USS Dahlgren as a "virtual ship," but it would more accurately be described as a cybernetic laboratory, a network of hardware and software distributed across Naval Warfare Centers from Rhode Island to Florida that can mimic the capabilities of a real vessel. Vehicles, weapons, computers, test ranges, crews—the USS Dahlgren has access to all of these assets and more, on-site at its headquarters at the Naval Surface Warfare Center Dahlgren Division (NSWCDD) in Dahlgren, Virginia; on loan from other Warfare Centers; or online by way of networking or simulation. The USS Dahlgren is thus able to experiment with new weapons, sensors, control systems and other equipment in an environment that resembles the conditions aboard a battleship but without running the full costs or risks of testing at sea.

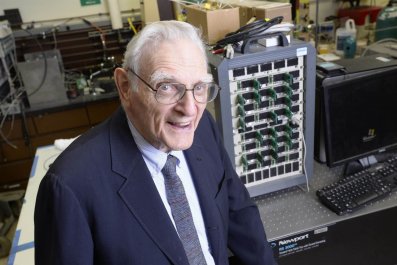

"The general term the Navy uses for an aircraft carrier at sea is 'a million dollars a day,'" says Neil Baron, a distinguished scientist and engineer for combat control at NSWCDD. "You've got 5,000 people. You've got four and a half acres of sovereign U.S. territory. You've got to pay for fuel and for food…. It's very expensive to have a ship at sea, especially if it's just doing testing."

Cost-Effective Training

In contrast, the USS Dahlgren's targeting system demonstration in August cost only $400,000 and involved four vessels and three aircraft—although a majority of those vehicles were simulated. The three large ships (a cruiser, a littoral combat ship and an aircraft carrier) were virtually represented on the Potomac River Test Range, helmed by three bases at NSWCDD and armed with artillery (5-inch and 30-millimeter guns) set on the range's waterfront. Two aircraft and their Hellfire missiles were simulated with the aid of the Navair RoadHawk, a tractor-trailer housing an avionics suite identical to that of MH-60S or MH-60R helicopters. The only genuine vehicles were the two drones observing the marks, one by air and one by sea.

Cost-effectiveness has been at the core of the USS Dahlgren since its inception five years ago. All of the vehicles, weapons, computers and other assets it utilizes were purchased by the Navy for other purposes. "It's all been paid for," says Nelson Mills, capabilities development lead at NSWCDD, of the Dahlgren's assets. "It was just that nobody's ever connected the dots like we've been doing here."

Those dots were connected by installing fiber-optic cables between Navy research laboratories and the Potomac River Test Range, which allows software on lab computers to communicate with weapons on the range and vice versa, thereby simulating the environment aboard a ship, where the two would be connected. The first test of the USS Dahlgren was firing one gun; now, after five years of development costing $3 million (a bargain), the Dahlgren can mimic multiple ships and fire multiple weapons on multiple targets.

Besides reducing the cost of testing, the USS Dahlgren makes experimentation safer and more practical, since real warships may have more pressing matters to attend to. Testing on terra firma also allows Navy engineers to get a closer look at how new acquisitions operate, as well as integration with already deployed hardware and software. More important, this environment curbs the danger inherent in testing combat systems. By connecting distributed assets, the USS Dahlgren is able to put greater distance and more precautions between experimental weapons and their attending crews than would be possible on actual ships, thereby better safeguarding sailors.

Real Ships Still the Final Test

But that isn't to say the USS Dahlgren doesn't come with risks. The Dahlgren's fiber-optic cables, which run between classified and unclassified laboratories, could be targets for cyberattacks. Additionally, the Dahlgren relies upon the Potomac River Test Range, which presents its own hazards and constraints. Stretching from Popes Creek, Maryland, to Smith Point, Virginia, the range can be a safety concern for neighboring communities, as well as an environmental threat to the river itself. Accordingly, the NSWCDD works with the Coast Guard to secure the range during tests, limits live-fire munitions and routinely performs environmental assessments.

The USS Dahlgren, as sophisticated as it may be, will never fully replace at-sea experimentation. "There are advantages to doing shipboard testing, both from firing the live ordinance and the proficiency of training the crew," explains Stephanie Hornbaker, head of the Warfare Systems Engineering and Integration Department at NSWCDD. "It's never going to eliminate some level of live-fire events at sea." While the Dahlgren can help ensure that new Navy technologies are as functional as possible before making it onboard a ship, real ships remain the final testing grounds. After all, the sailors relying on that equipment won't be fighting in simulations.

There are plans to expand the USS Dahlgren to include a 57-millimeter gun and possibly to begin testing more futuristic weapons, such as electromagnetic railguns, which fire projectiles using electricity instead of traditional propellants, and solid-state lasers, which focus energy to produce a beam that can range from irksome to deadly. Beyond that, virtual reality—rather than the sky—is the limit.