An obsidian blade found in Texas decades ago could shed new light on a Spanish expedition that set out in search of a fabled "city of gold" during the mid-16th century.

The unassuming artifact, which measures around 2 inches in length, may have been dropped by a member of the expedition, research conducted by anthropologist Matthew Boulanger of Southern Methodist University suggests.

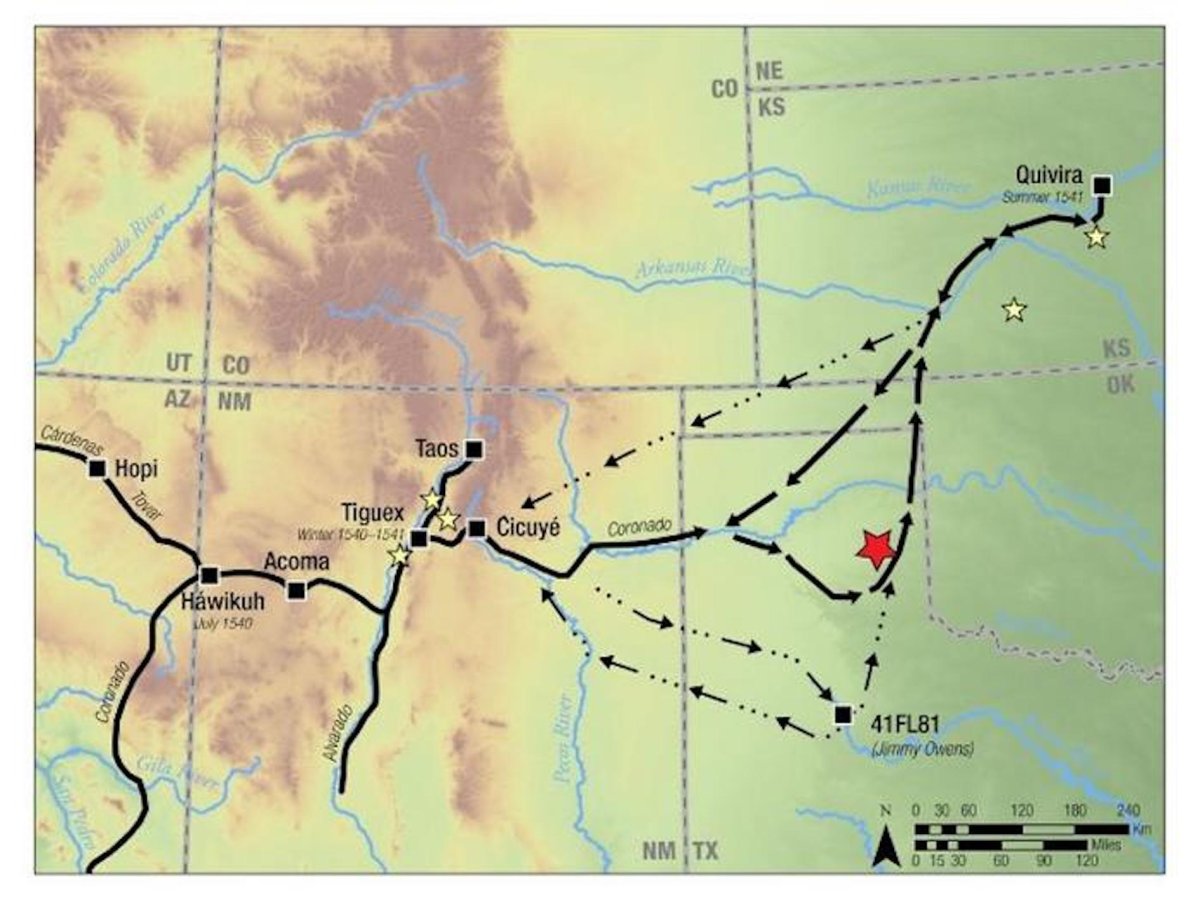

Led by Spanish conquistador Francisco Vázquez de Coronado (1510-1554), the expedition took place between 1540 and 1542. In this period, Coronado and his party, which included Indigenous Mexicans, trekked across parts of what is now Texas, New Mexico, Arizona and Kansas.

Boulanger's latest research, published in the Journal of the North Texas Archeological Society, describes how the obsidian blade could unravel the mysteries surrounding the route that the expedition took hundreds of years ago.

"The path of Coronado's expedition through the American Southwest and the southern Great Plains has been a matter of much debate and discussion," Boulanger told Newsweek. "The exact path he took through New Mexico is well known because his group visited many of the large towns occupied by Indigenous Puebloan peoples. Reconstructing the journey through New Mexico is a simple matter of connecting the dots from each of the towns that they visited."

"However, once the expedition moved eastward onto the Great Plains, they were confronted with a vast flat plain with no clear landmarks to describe—there are no geographical dots to connect," Boulanger continued. "So even though we have written journals from the expedition's members, we have no way of knowing where exactly the group was until they arrived at the [Wichita Indian] town of Quivira in southern Kansas."

For over a century, archaeologists and historians have debated the exact path of the expedition through Texas and Oklahoma. But these researchers have all worked from the same limited source of data: the vague descriptions of canyons, valleys and streams mentioned in the expedition's journals.

However, the blade made of obsidian—a type of naturally occurring volcanic glass—may provide physical evidence of the path taken by the expedition, if corroborating evidence can be found, according to Boulanger.

"At present, only one other Coronado-related site has been identified in Texas, and this is about 150 miles south of the ranch on which this obsidian piece was found. So this little piece of obsidian represents a second dot allowing us to better reconstruct the journey Coronado took through the Texas Panhandle," he said.

Boulanger's latest research was sparked by a chance encounter after a meeting of the North Texas Archeological Society. The anthropologist was talking to one member of the group, Charlene Erwin, who asked the researcher if he would be willing to examine an obsidian artifact that her deceased father-in-law had found on a ranch in the 1930s near McLean in the Texas Panhandle. The item has been in the family's possession ever since.

The father-in-law picked up many artifacts from the ranch but does not appear to have recognized the significance of the obsidian piece, according to Boulanger.

Since obsidian does not occur naturally in Texas, any artifacts made from this volcanic glass found in the state must be products of trade and exchange with people living near a source.

"The nearest source of obsidian to the Texas Panhandle is in northern New Mexico—about 300 miles to the west. I agreed to have a look at the collection, just as a public service and because of the rarity of obsidian in Texas archaeological sites," Boulanger said.

The anthropologist conducted a chemical analysis of the blade, determining that it originated in the Sierra de Pachuca range of Central Mexico. Indigenous people produced cutting tools from obsidian in this region until the Spanish conquest of the area in the 1500s.

But how did an obsidian blade from Central Mexico end up in the Texas Panhandle? Given that there is no clear evidence of a trade network connecting the Indigenous peoples of the two regions before the conquest, the anthropologist considered three hypotheses in the study.

The first is that Erwin's father-in-law obtained the blade through trade or exchange with other collectors. The second is that the blade is a hoax—one intended to garner attention for Erwin and his collection. The third is that the artifact may represent an object discarded by one of the few Spanish expeditions that passed through the Texas Panhandle during the 16th and early 17th centuries—in particular, the one led by Coronado.

This expedition passed through the Texas Panhandle in 1541. And while Coronado's exact route across the region is uncertain, current understanding suggests that the party passed through or close to McLean, where Erwin's father-in-law grew up and collected artifacts.

After assessing the available evidence—including piecing together the father-in-law's travels and interviewing the family—Boulanger determined that the third hypothesis is most likely.

"We propose that this small unassuming artifact fits all of the requirements for convincing evidence of a Coronado presence in the McLean area," the authors wrote in the study. "It is the correct form of artifact, the artifact is fully consistent with other such finds, it is the correct material, it was found in the correct location, and there is no indication of an intentional hoax."

Obsidian artifacts were often left behind by Spanish expeditions in the region, like the one led by Coronado, because of the practice of bringing Indigenous Mexican allies with them. These allies brought their own tools and weapons, such as obsidian blades. The brittle blades were discarded when they broke, leaving behind evidence of the routes taken, which is what may have occurred during the Coronado expedition.

Unfortunately for the conquistador, he never did find the city of gold he was searching for, eventually realizing that the tales he had been told were fabrications.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Aristos is a Newsweek science reporter with the London, U.K., bureau. He reports on science and health topics, including; animal, ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.