Deborah Cutkelvin, a hairstylist in Brooklyn, always keeps the contact information for her dermatologist on-hand. She does it for her clients—over the years, she's seen more than her share of distraught women complain of hair loss, as well as scalps that need medical attention rather than a touch-up. The doctor often treats her clients for alopecia that's a result of lifetimes of abuse—braiding, ironing and relaxing hair with gallons of lotions and creams that contain more chemicals than a plumber might use in a month of unclogging drains.

Cutkelvin's business, Seymonnia's Hair Salon, is one of thousands in Brooklyn that cater to the specific needs and preferences of black women. Because her salon has many local competitors, she tends to stick with products that produce the results her clients expect when they pay $50 to have their hair relaxed. These products contain lye, a chemical that seems to magically undo the curl of hair. It's also a highly effective agent for cleaning the crud out of ovens, unclogging drains and dissolving animal carcasses, and it's even used at some funeral homes for chemical cremation. Lye has been a mainstay in hair relaxers since the early 1970s, and many black women who want straight hair have come to view the pain and burning relaxers can cause as simply part of a routine salon experience.

Some hair-care companies try to downplay the use of lye in their relaxant formulas, but Cutkelvin says it's a ruse. "It doesn't matter if the label says 'no lye,' 'less lye' or 'shea butter,'" she says. "Even when it says no lye, that's not true." Cutkelvin is one of multitudes of hairdressers who question the safety of hair products for black women.

"It is like the Wild, Wild West when it comes to chemicals," says Nourbese Flint, policy director at Black Women for Wellness, an advocacy and education nonprofit. "The FDA doesn't have any power to regulate." The Food and Drug Administration's policies on regulating cosmetics and beauty products have remained largely unchanged for nearly 80 years, and that gives companies virtually all of the power to manufacture and market whatever they want without approval from the federal agency. Unlike with drugs, the FDA does not approve cosmetic and beauty products, nor does the agency have mandatory recall authority over any products that are suspected of causing adverse side effects.

It's a problem seen across the entire spectrum of beauty products in the U.S. Women may want straighter hair, softer skin, redder lips, longer lashes or shinier nails (or at least society suggests they ought to), so companies deliver on many of these promises by adding substances to their products that are allergenic, toxic or carcinogenic. These chemicals don't only cause run-of-the-mill skin irritation: Some experts say the common ingredients in beauty and cosmetic products are linked to cancer and endocrine disruption. Other research suggests exposure to certain chemicals in beauty and hair products may raise risk for pregnancy complications such as miscarriage and low infant birth weight. Longtime use of certain cosmetics is suspected to have serious health repercussions, but a lot of the industry's efforts to address the problem relies on unsound science and a lot of false marketing.

In the U.S., black people account for a disproportionate amount of spending in the beauty and cosmetic industry. While 13 percent of people in the country are black, this demographic is responsible for 22 percent of the $42 billion cosmetics industry, according to the Environmental Working Group (EWG), a Washington, D.C.-based research organization that monitors the safety of consumer products and lobbies for stricter regulations. EWG recently released a report that finds roughly three-quarters of products marketed specifically to black women contain high quantities of hazardous and toxic chemicals such as parabens and formaldehyde.

In the past five years, EWG has spent some $600,000 on building up a comprehensive public database on beauty and cosmetic products, known as "Skin Deep." It provides assessments on the safety of nearly 65,000 commonly sold products by 2,069 brands.

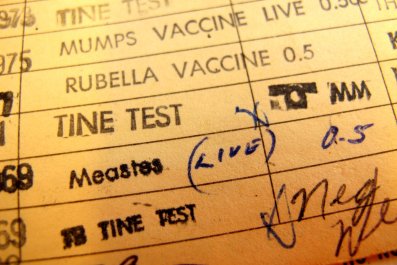

Recently, EWG issued a report that focuses specifically on 1,177 hair-care and beauty products marketed to women of color. In particular, the report looked at the safety of ingredients in 15 hair relaxers on the market and gave them an average score of 8.1, which is in the high-hazard range. (EWG reviews existing research on chemicals and additives and each one is scored between 1 and 10.) While many of the hair-care products reviewed in this new report were labeled "lye-free," the researchers found the product formulas contain other caustic ingredients such as parabens and formaldehyde-releasing preservatives.

EWG also found toxic chemicals in makeup formulations analyzed in the report, including lipsticks, foundations and concealers. For example, methylisothiazolinone, a preservative, was listed as an ingredient in 118 products in the analysis. The chemical is a known allergen and is partially banned in Europe by the European Commission Scientific Committee on Consumer Safety. In the U.S., however, the FDA allows cosmetic companies to use the additive in small doses but with limited oversight.

"The FDA needs to have more authority; they need to be able to have recall authority if products have been shown to cause harm," says Nneka Leiba, the EWG's deputy director of research and a co-author of the report. "We should not be guinea pigs of these products."

In recent years there have been a number of instances when consumers' anxieties are warranted. Last year, the FDA issued a safety alert regarding hair-care products produced by the company WEN by Chaz Dean, after receiving reports from consumers of hair loss, hair breakage, balding and rash associated with a line of cleansing conditioners. In July, the FDA said it had received 127 reports from consumers about WEN conditioner mishaps, and that number ballooned to 1,386 by November. When the FDA finally launched an investigation of the company, it learned that WEN had fielded some 21,000 complaints but never reported the adverse effects to health officials because current laws don't require it to do so.

Because of loopholes in product labeling, a little tweaking of marketing practices allows companies to continue to sell their products even when health risks are known. In 2011, the FDA sent a letter to the CEO of Brazilian Blowout, noting that its hair-straightening product contains methylene glycol, which is a reactionary chemical compound that forms when formaldehyde combines with water. A year later the company settled a class action for $4.5 million. As part of the settlement, the company agreed to no longer market its product as "formaldehyde-free."

Regardless, most industry experts and many lawmakers agree there isn't enough federal oversight to sufficiently protect consumers from deleterious chemicals in cosmetic products. Under current guidelines, companies are responsible for safety testing, which provides plenty of leeway to formulate products as they wish, says Tina Sigurdson, assistant general counsel at the EWG. Sigurdson says that when consumers report adverse effects from the chemicals, the FDA doesn't have the power to take any meaningful legal action on its own. In order to do so, the FDA would have to call upon the U.S. Department of Justice, an agency that typically doesn't have time to worry about shampoo.

Current beauty industry regulations were put in place in 1938, when Congress passed the U.S. Federal Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act. Under this law, it is the responsibility of cosmetic companies to ensure their products are safe, but they're only obligated to submit proof of product safety to the FDA when health officials are forced to intervene.

Only one other piece of legislation that offers protection to consumers from potentially dangerous products has passed since 1938: the Fair Packaging and Labeling Act, enacted in 1968. This law requires cosmetic companies to list all ingredients in their products on labels. But there are still loopholes: The formulations of product fragrances are exempt, as they are considered "trade secrets." Products intended for professional use, such as those employed by salon workers, are also exempt from mandatory labeling.

It's clear to many members of Congress that the current laws require substantial overhaul . In April 2015, Senators Dianne Feinstein of California and Susan Collins of Maine introduced the Personal Care Products Safety Act, which would provide the FDA with authority to recall products. Should the bill pass, the agency would be required to investigate five potentially dangerous chemicals each year that are widely used throughout the beauty industry, such as methylene glycol and parabens.

"People actually think that if they go and buy hair products they've been approved by the FDA, but that's not true," says Representative Frank Pallone Jr., a New Jersey Democrat who co-sponsored a bill that would give the FDA mandatory recall authority and the ability to collect data on chemicals used in products. The legislation would also require manufacturing facilities to register with the FDA and pay user fees that, in turn, would fund industry regulation. In this case, the proposal would generate about $20 million annually, says Pallone.

Both bills have received bipartisan support, in part because even leaders in the industry are advocating for more consistent regulations. As of now, individual states can determine their own regulatory schemes, which ultimately makes it more challenging to run cosmetics companies because distributors need to keep up with the nuances of laws in all 50 states, and that can be costly and a logistical nightmare.

Linda Loretz, chief toxicologist for the Personal Care Products Council—an industry trade organization with members from companies that account for at least 85 percent of the industry—agrees more oversight is needed. However, she's skeptical of EWG's reports, which she says are based on research that's frequently taken out of context, such as studies that assess safety of a chemical on mice or research done in test tubes in a lab. " You have to look at what the relevance is to real, live humans, what the relevance is in real-life circumstances," she says. "These are ingredients that have been used very widely, they've been studied thoroughly, they have been assessed by expert bodies in the U.S. and also in Europe."