An excellent test for assessing the constitutionality of any governmental action is to switch the names and political parties of the actors involved. If the outcome is the same, it is a good sign there is some neutral principle at work. If the outcome is not the same, then there is a good chance that partisanship, not principle, is guiding the analysis.

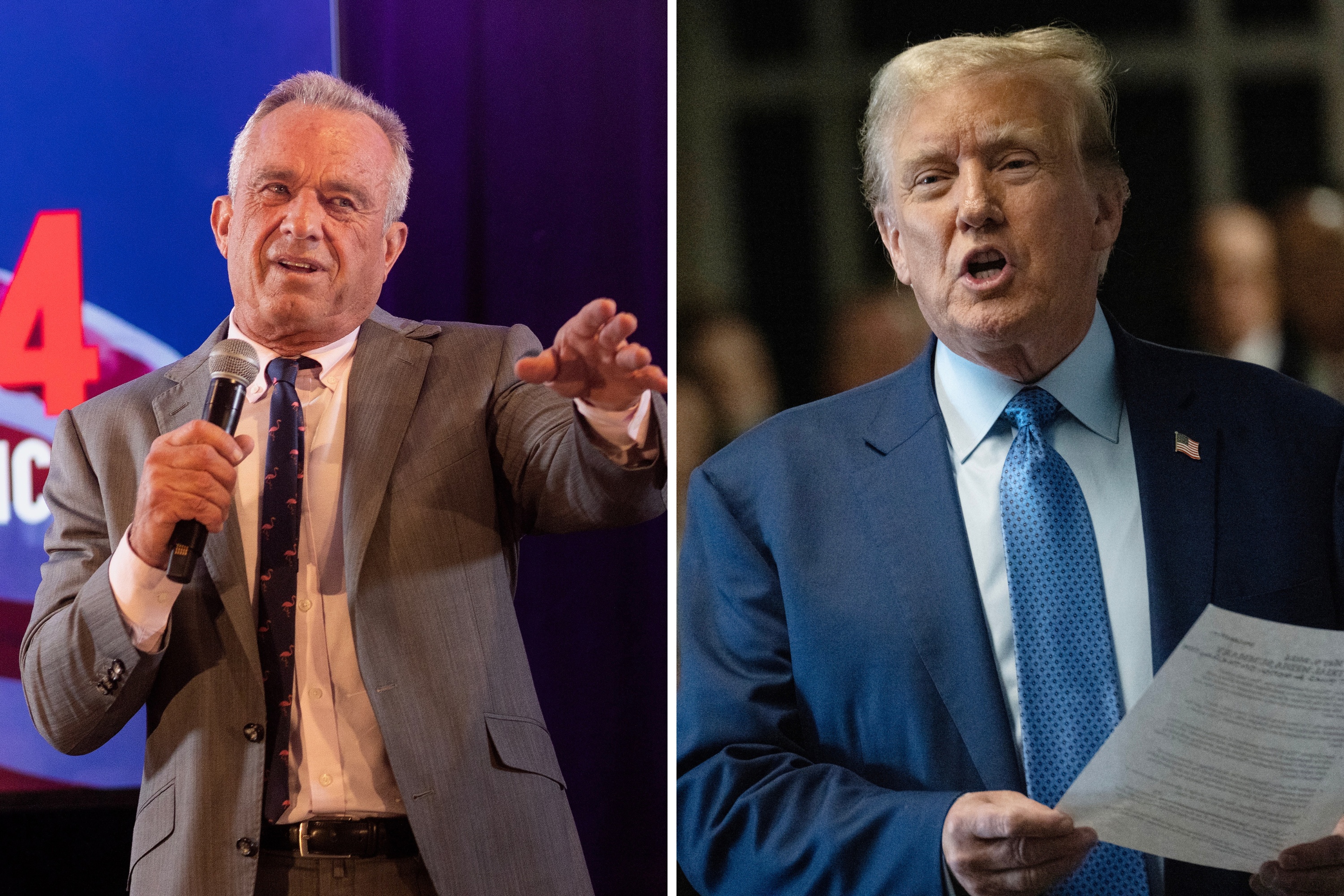

The impeachment inquiry against President Biden that House Speaker Kevin McCarthy announced last week clearly fails this test. In 2019, McCarthy, then Republican minority leader in the House, complained loudly and often that the full House should have authorized the House's impeachment inquiry and that that the majority Democrats should not have authorized the impeachment inquiry focused on then-President Donald Trump's request for "a favor" from Ukraine's president.

McCarthy and the leaders of the Republican charge to impeach Biden are proceeding without any such authorization. McCarthy has now said that he is proceeding in this manner because then-Speaker Nancy Pelosi had "changed the precedent" in 2019, when she allowed an impeachment inquiry without full authorization by the House. Of course, a few weeks later, the full House did authorize an inquiry culminating in Trump's first impeachment.

McCarthy also complained, in 2019, that Democrats were not prioritizing the national budget or "all the other things the American people want"(The government then was nearing a budget shutdown, just as it is now). Now, McCarthy has shown no concern prioritizing impeachment over the possibility of another government shutdown.

While there is a lot of McCarthy's hypocrisy on display, there is no principle in sight.

The Republican-led inquiry arguably makes sense as an exercise in political theater. Casting it as impeachment-related supposedly will broaden the subpoena and investigative authority of the three committees charged with searching for evidence of any Biden misconduct. Perhaps more importantly for Republicans, it may draw attention away from Trump's legal troubles and provide a showcase–or, more accurately, a political circus–for "alternative facts" and outlandish conspiracy theories. As we know from past attempted presidential impeachments, that kind of table pounding will not substitute for the kinds of evidence and legal support that presidential impeachments require for their legitimacy.

At a minimum, some credible proof of "treason, bribery, and other high crimes or misdemeanors" on the part of the person who is threatened with impeachment is usually the basis for initiating such an inquiry. The House need not come up with exhaustive evidence, but it usually does some fact-finding before launching impeachment inquiries. It is telling that the inquiry unleashed by McCarthy lacks anything remotely like the factual foundations for the impeachments of Richard Nixon, Bill Clinton, and Donald Trump.

For example, in Nixon's case, the House Judiciary Committee and the Senate Select Committee on Watergate had conducted meticulous investigations and fact-finding before the former began an impeachment inquiry of Nixon. In Bill Clinton's case, the House Judiciary Committee did no fact-finding of its own but deferred to the allegations and evidence set forth in a report assembled by Independent Counsel Ken Starr and his team (including Brett Kavanaugh, now a Supreme Court justice). And, with Donald Trump in 2019, the House Judiciary Committee did not conduct an impeachment inquiry until after it received the House Intelligence Committee's report of its weeks-long investigation into the nature and consequences of the "favor" then-President Trump requested from Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky.

The current inquiry also tests several constitutional safeguards against the abuse of impeachment authority. One of the most important is the division of impeachment authority between the House and the Senate. As Alexander Hamilton explained in The Federalist Papers, impeachments "will seldom fail to agitate the passions of the whole community, and to divide into parties more or less friendly or inimical to the accused. . . In such cases, there will always be the greatest danger that the decision will be regulated more by the comparative strengths of parties, than by the real demonstrations of innocence or guilt."

If the political accountability of House members did not keep them in check, the Senate was expected—given its members' longer terms and final decision-making on important matters such as removal and confirmation—to be capable of more dispassionate, less partisan decision-making. Perhaps not surprisingly, a Democratic Senate acquitted Clinton, a Republican Senate acquitted Trump in his first impeachment trial in 2019, and Republicans controlled enough seats in the Democratic Senate in 2021 to thwart the two-thirds approval necessary for Trump's conviction then.

McCarthy and other Republican leaders in 2019 complained that the House was wasting its time in considering the impeachment of Trump since the prospects clearly favored his acquittal in the Senate. But McCarthy and other Republicans leaders now manifest no concerns about wasting the time the inquiry will take on its way to the inevitable outcome of acquittal of President Biden in the Senate.

The fact that the Senate acquitted Clinton in 1999, and Trump twice during his single term, undermines further McCarthy's justifications for initiating an impeachment inquiry of Joe Biden. In 2019, all Republicans except for Sen. Mitt Romney of Utah rejected any evidence of wrongdoing by Trump (who has since been indicted for more than 90 felonies), proclaimed Biden—and especially Hunter Biden—as corrupt, and maintained that Trump's actions did not rise to the level of any impeachable offense.

Though seven Republican senators defected to vote to convict Trump in his 2021 impeachment trial over his actions on Jan. 6, others voted to acquit because they said they did not believe the evidence, consider any of it as showing he committed any impeachable offense, or that Trump was no longer in office at the time of his trial. Thus, to the extent Senate precedents are pertinent, they favor not proceeding with any impeachment inquiry of Biden because of the likelihood of acquittal and the absence of any evidence of misconduct, much less anything remotely close to Trump's abuses of power in 2019 and 2021.

With a slim majority of seats in the House, McCarthy has the numbers to impeach. But he has nothing else, besides partisan fervor, to back the inquiry he has set in motion. It is sadly telling that many Republicans, whose party once proclaimed itself the defender of "law and order," will ignore the fact that Donald Trump has been indicted for more than 90 felonies in favor of a witch hunt they desperately need for political cover.

The longer the circus lasts, the more the American people are likely to hold McCarthy and his Republican colleagues accountable for the absences of principle and facts to guide their inquiry.

Michael Gerhardt teaches constitutional law at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, has written and consulted extensively on impeachment, and is the author of the forthcoming book, The Law of Presidential Impeachment (NYU Press).

The views expressed in this article are the writer's own.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.