Updated | When CIA veterans complain that their old outfit needs to be less risk-averse, I don't think they have Robert Levinson in mind.

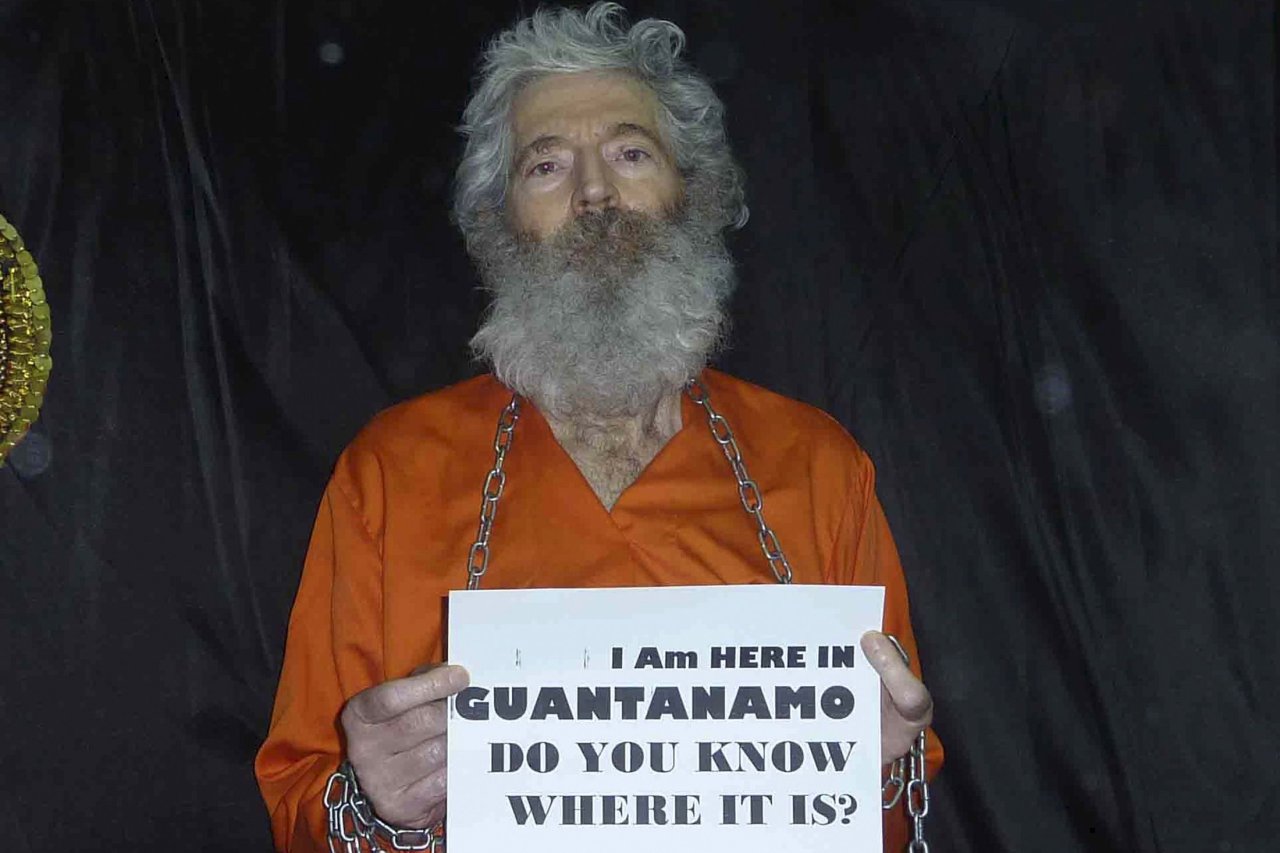

The retired FBI agent famously vanished nine years ago on Kish Island, a kind of Iranian Grand Cayman frequented by shadowy arms dealers, counterfeiters, smugglers and, of course, spies. Almost certainly, he was kidnapped by Iranian operatives.

Years would pass before the truth emerged that Levinson had been working for a CIA analytical unit that was making an end run around the espionage wing of the agency and had no business running amateur spies. Now the Iranians have him—if he's still alive.

All this, and much, much more about the Levinson affair, has been dug up and stitched together by the distinguished New York Times reporter Barry Meier in his important and troubling new book, Missing Man: The American Spy Who Vanished in Iran. Judging by Meier's account. if ever there was a case for blowing up the CIA and starting over, as many agency oldtimers have argued, the Levinson affair is it. A good beginning would be the formation of a select congressional committee to air out the whole sordid mess.

For a long time, the facts behind Levinson's disappearance was one of Washington's best kept secrets. The official line was that Levinson, an organized-crime specialist who had been freelancing since his 1998 FBI retirement, was working on "private business" when he went to Kish. That was only very narrowly true: Levinson's "private business" was spying for the CIA.

The former G-man had even ginned up his own cover story for his mission: that he was investigating a cigarette-counterfeiting case in Iran for British American Tobacco (BAT), a sometime client. In a move that could have been lifted from Burn After Reading, he typed up a phony assignment letter on BAT stationery—a ruse that would have fallen apart with a single call to the company.

The truth was, however, that Levinson went off to Kish in hopes of turning Dawud Salahuddin, a U.S.-born fugitive who decades ago had carried out an assassination of an Iranian exile dissident outside Washington, D.C., into his informant.

A handful of national security reporters, myself included, eventually learned that Levinson had actually been working for "rogue" CIA analysts who had violated agency rules by using him as a spy, that agency officials had allegedly lied to congressional overseers about it and that people had been fired. However incomplete, it was a hell of a story. But we sat on it after hearing arguments—from Levinson's friends and family, their U.S. senator, Bill Nelson of Florida, and of course the CIA—that revealing Levinson's agency ties could be fatal.

"The simple fact is that we didn't want to do anything to jeopardize Bob or complicate efforts to free him," Meier writes. "Perhaps that was naïve. But it was a decision that my editors at the Times and I never regretted or second-guessed."

In late 2013, however, with no movement on Levinson's case, and smelling a cover-up, the Associated Press and The Washington Post published the true story behind Levinson's disappearance. Reporters Matt Apuzzo and Adam Goldman wrote that Anne Jablonski, a "highly regarded" senior CIA intelligence analyst who long shared Levinson's enthusiasm for tracking Russian gangsters, offered her friend a gig to provide reports to the agency's Illicit Finance Group. The unit tracked black market arms-dealing and money laundering. After Levinson vanished, Apuzzo and Goldman reported, CIA officials lied to Congress in closed hearings as well as to the FBI about his extensive work for the group over the year before he disappeared.

In Meier's version of events, Senator Nelson asked CIA Deputy Director Stephen Kappes about Levinson's status during a closed-door meeting of the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence in the fall of 2007, several months after he disappeared. "Kappes sat silently for a few moments and then responded he didn't know what Nelson was talking about," Meier writes. He told Nelson that neither he nor his boss, CIA Director Michael Hayden, "were ever alerted about Bob's disappearance and they didn't know anything about the episode."

But did anyone at the CIA green-light his mission to Iran?

"Back in December 2005, when Bob was pitching Anne on projects he might take on when his CIA contract was approved," Meier writes, "he sent her a lengthy memo about Dawud's potential as an informant..." But the CIA's internal inquiry after he disappeared "hadn't found a 'smoking gun," an agency investigator told Levinson's wife, Christine.

"If people at the agency ever talk—or are compelled to do so," Meier tells Newsweek, "perhaps we'll get an answer to that question. But folks on the analytical side were apparently eager to score points, and there is nothing to suggest in the documents I reviewed to indicate that anyone at the CIA ever suggested to Levinson, prior to his decision to go to Kish, that he stand down."

Levinson had virtually circled the globe for Jablonski, sometimes using fake names, plying confidential informants for intelligence on a wide range of targets. He had "inundated" Jablonski with dozens of investigative reports, Meier writes, on "subjects ranging from Russian crime to narcotics smuggling to arms trafficking" to inside dope on Venezuela's firebrand socialist leader Hugo Chavez, who was cozying up to Iran. He was also relaying tips about shadowy investments by Iranian officials in Canada.

He was having great fun. Working for the CIA, Levinson told Jablonski, "seems like something too good to be true..." She, too, was thrilled. So was the unit's boss, Tim Sampson: "This guy is a damn GOLD MINE," he told her. "You rock our world," she added. But she also knew that running agents was against the rules. She warned Levinson to keep their financial arrangements "just between us girls." It was an arrangement that had to be kept out of higher channels, just like his intelligence reports, which she had him routinely mail to her home, not the office.

"We teeter on the edge of some legal issues here—since we're NOT anything but an 'analytical shop,'" she wrote Levinson when she brought him aboard in 2006. "So we have to kind of shape things a bit differently (same info, different prism) and maybe work with you to change the 'format' of the material you send."

But it annoyed her to have to avoid "pissing off the folks who are SUPPOSED to be collecting this kind of material for us but are too busy jumping through bureaucratic hoops and making excuses," she told Levinson in an email Meier obtained. By those "folks," Jablonski meant the CIA's directorate of operations, the people responsible for recruiting and running foreign spies. But from her vantage point, the cloak-and-dagger set wasn't getting anything useful on Iran's shadowy network of nuclear suppliers and money launderers.

The analysts had long chafed over the spying side's swagger and condescension toward them. At one time, the analysts "were barred from setting foot inside the cafeteria where the operatives ate," Meier writes. That had certainly changed. With the rise of Al-Qaeda in the 1990s, female counterterrorism analysts especially were becoming analytical stars. After the 9/11 attacks they took a lead role in tracking Osama Bin Laden (a role dramatized in the movie Zero Dark 30). And they began moving into the field to work more closely with the case officers, as the CIA spy handlers were called. Managers in the once-derided analytical side sensed an opening. The head of the branch overseeing the Illicit Finance Group, Meier writes, convened a meeting of analysts in the CIA's auditorium in 2004 during which he "declared that under his watch they were 'going to destroy' their rivals on the agency's clandestine side."

But Jablonski's flip crack to Levinson about an inept operations directorate corroborated what anonymous CIA sources had been saying—and CIA representatives denying—for years: Iran was a black hole. As Meier writes, "the CIA's presence in Iran was all but nonexistent." The agency's spies in Iran (and in portions of Lebanon where Tehran-backed Hezbollah ruled) had been wiped out through a combination of caution and CIA pratfalls. So in 2006, when Jablonski brought Levinson aboard, agency managers were nearly hysterical about intelligence gaps in relation to Iran's nuclear designs and operations in U.S.-occupied Iraq.

"The CIA wanted the Illicit Finance Group to gather information to help U.S. officials anticipate Iran's response to new sanctions and also dig up dirt that could be used as political ammunition against his leaders," Meier writes.

Levinson was their man—or at least one of them.

Returning from a June meeting at CIA headquarters, the ex-FBI agent had a bounce in his step, recalled his longtime friend Ira Silverman, a veteran journalist who had retired from NBC after an illustrious career with the network. With the new CIA contract, Levinson's money woes were behind him. "He looked buoyant again, like his old self," Meier writes.

As they sat down for lunch at Clyde's, a venerable Georgetown bistro, Levinson told his reporter friend about his meeting in Langley.

"Iran," he said, 'is the flavor of the day."

In 2002, Silverman had interviewed Salahuddin, the fugitive assassin, in Tehran and they had stayed in touch. The exile had been voicing signs of disaffection with the Iranian regime. Maybe he was ready to do something important for the U.S. to erase, or at least reduce, the murder charge hanging over his head.

Levinson hoped so. It was certainly time to find out.

This story has been updated to include a quote from the author of the book, Barry Meier.