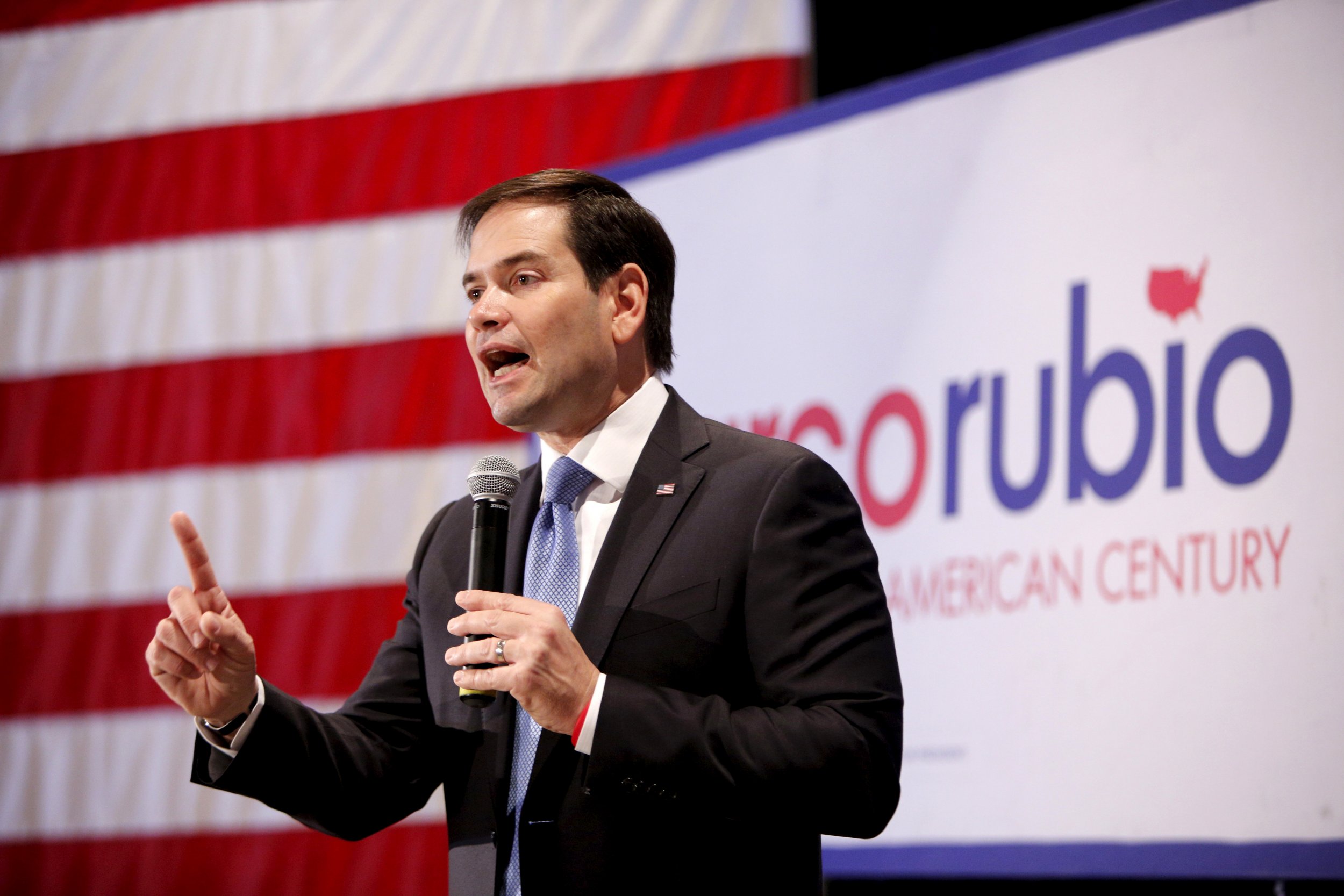

Despite polls showing that Marco Rubio is doing relatively poorly in Iowa and New Hampshire, and is not expected to win in the Southern states that make up the base of the Republican Party vote, the Florida senator is seen as one of the leaders in the Republican race.

Compared to the other two current polling frontrunners, Donald Trump and Senator Ted Cruz, Rubio is increasingly being viewed as the more mainstream candidate in the race. If so, he may have a very different track to succeed: He will have to clean up in an unusual place for Republicans—the Blue States.

In a general election, Rubio has practically zero chance of getting an electoral vote from the vast majority of the Northeast and West. Yet, in a primary campaign, states like California, New York and Illinois may provide the path to victory.

What may be surprising about this strategy is that he is far from the first candidate to try to use it. He wouldn't even be the only one this year. During her early struggles, there had been discussion of a Hillary Clinton "Southern Firewall"—where she would fend off a Bernie Sanders or Joe Biden run by sweeping the Southern states that will undoubtedly vote Republican in November.

This strategy of looking to an electorate that the candidate had no hope of winning in the general election to ward off a strong primary challenge goes back to the very beginning of the presidential primary. Neither Clinton nor Rubio may want the association, but William Howard Taft used this exact plan to fend off Teddy Roosevelt in the 1912 presidential campaign.

Prior to 1912, the primaries were not a real part of the presidential selection process. Only a handful of states had the primaries, and they were not viewed as an important method of choosing candidates.

Teddy Roosevelt's decision to try once again for the presidency after a four-year layoff changed everything. Roosevelt may have hoped that Taft would bow out and give him unimpeded access to the nomination, but that didn't happen.

Perhaps more surprising to Roosevelt was that numerous Republican leaders who would otherwise have been excited by Roosevelt decided to fall into line and back the uninspiring incumbent. As a result Roosevelt decided to bank on a new plan of proving his popularity and rolling up delegates in the nascent primary votes.

After losing two primaries to Senator Robert LaFollette, and then being beaten in the critical New York primary by Taft in a highly charged and very questionable race, Roosevelt won nine of the next 10 races, usually by large margins. At that point, Roosevelt had a very strong claim to being the people's choice for the nomination.

Taft had the ace in the hole—and that was a Southern Strategy. None of the states in the South had a primary vote. And not one of the 11 old Confederate States had cast an electoral vote for a Republican since Reconstruction ended 36 years before, and with a sole exception of Tennessee in 1920, none would vote that way until Catholic Al Smith headed the Democratic ticket in 1928.

But the Southern votes counted just as much as the Northern states in the Republican nomination fight. And for the most part (with the notable exception of North Carolina), Taft had those votes locked up.

To a good degree, they were cast by the patronage hires who owed their jobs to the president, and they certainly weren't about to turn on him now. The lack of actual Republican voters, not to mention elected officials, in the South made it clear that there would no protest of this near-uniform vote for Taft.

The result was that Taft was able to roll the convention and easily recapture the nomination—though the seemingly corruption nature of his playing with the rules helped doom the party to a humiliating and potentially dangerous third-place showing in November.

The situation isn't an exact mirror of Rubio and Clinton's current plan—after all, they actually have to win over the voters. Momentum will undoubtedly also count for a lot more now.

Back then, there was no real polling, and it is certainly possible that the Republicans felt that Taft could carry the day in the general election. But the strategy has some remarkable similarities, most notably that Rubio and Clinton would be counting on states whose Electoral College ballots will almost certainly be going to the Republican candidate in November.

This odd development will certainly not prevent them from relying on it. But Taft's ultimate fate in the general election should put a damper on any enthusiasm for this strategy.

Joshua Spivak is a senior fellow at the Hugh L. Carey Institute for Government Reform at Wagner College in New York. He blogs at http://recallelections.blogspot.com.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.