The impact that 3-D printing is having on our world is impossible to ignore. It's not new technology, but its 30-year history has been characterized by deceptively slow growth —until now. 3-D printing has recently emerged as a force poised to disrupt a significant portion of the $10 trillion global manufacturing industry.

Already, the printing of standard consumer products—bowls, plates, smartphone cases, bottle openers, jewelry and purses (made from mesh)—has gone from a hobby to a nascent industry. Dozens of websites now sell goods made with 3-D printers, and retailers are starting to get in on the action.

It is also affecting the aerospace industry. For instance, SpaceX, the space transport company founded by Elon Musk, recently announced it will 3-D-print much of the rocket engine used in the Falcon 9 launch vehicle. Boeing currently 3-D-prints over 200 parts for 10 different aircraft platforms. And Planetary Resources, the world's first private asteroid mining company, is 3-D-printing much of the spacecraft that will travel to and prospect near-Earth asteroids.

I first met Aaron Kemmer, Michael Chen and Jason Dunn, a trio of bold-minded innovators, during the summer of 2010 at Singularity University (a training center for entrepreneurs, corporate executives and government officials) during the Graduate Studies Program. It was a passion for space that brought them together.

"We were all serial entrepreneurs hunting for a big idea," says Kemmer. "We wanted to start a company that would help open the space frontier. We were definitely not thinking the way forward was going to be 3-D printing."

It was the university's chair of robotics and three-time shuttle astronaut Dan Barry who pointed them in that direction. "We knew a little bit about 3-D printing," says Chen, "but only because Jason, with his aerospace background, had played with it a little in college. But when we were doing analysis—just looking at all the different exponential technologies and trying to come up with our idea—Dan Barry kept wandering over and telling us he had been to the International Space Station and wow, having a 3-D printer on the ISS would sure be useful."

Eventually, they decided to figure out how useful.

"It's a supply chain problem," explains Dunn. "The ISS is at the back end of the longest, most complicated and most expensive supply chain in existence. Launch costs are roughly $10,000ten thousand dollars a pound. And any object sent into space has to be durable enough to survive the eight minutes of high g-forces it takes to get out of the Earth's gravity well."

That means heavier objects—and every extra pound costs more money. And with extra weight, more fuel will be needed to get the spacecraft off the planet—which means even more money.

Plus, when parts aboard the station break, resupply can take months and months. This is why there are over a billion parts manufactured for the ISS that were bought and paid for in advance of their use. And after doing more research, Kemmer, Dunn and Chen realized that 30 percent of these parts were plastic—meaning they should be printable with already available, off-the-shelf 3-D printing technology.

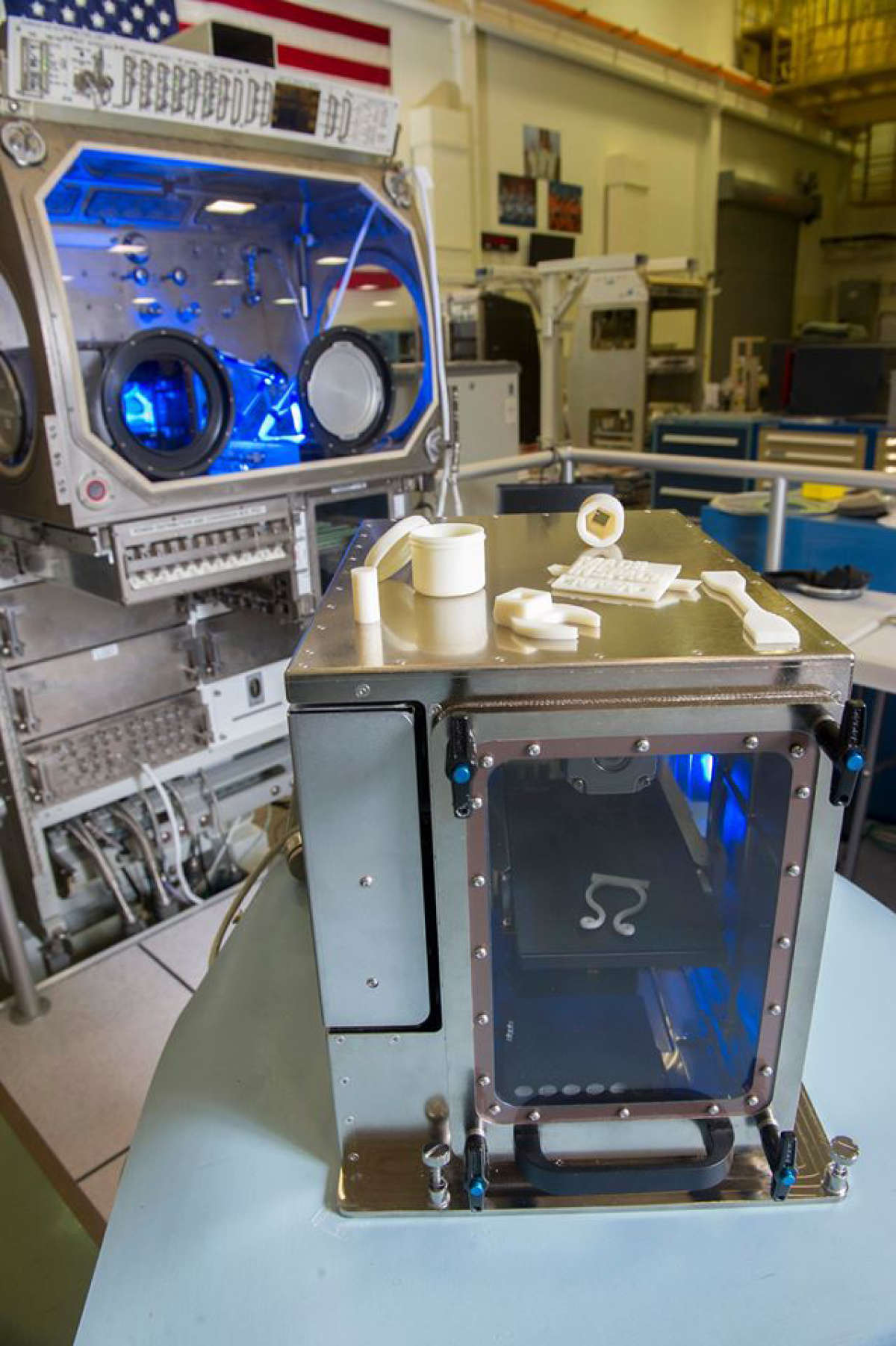

This led to the birth of Made in Space, humankind's first off-world 3-D printing company. Their first offering, launched to the ISS in the fall of 2014, is fairly simple: a 3-D printer that prints plastic parts. In itself, this will bring on a manufacturing revolution of sorts. "The first 3-D printers on the ISS will be able to build objects that could never be manufactured on Earth," says Kemmer. "Imagine, for example, building a structure that couldn't withstand its own weight."

Made in Space's next iteration will be able to print with multiple materials, including both plastics and metals, which means that sometime in the next five years, 60 percent of the parts in use on the ISS will be printable. And just behind this version is the real game changer: a 3-D printer capable of printing electronics.

Consider the latest trend in satellite technology: CubeSats. These are tiny satellites weighing only a kilogram and made in the shape of a 10-centimeter cube. They're so simple to build that almost anyone can pull it off (free instructions are available online), yet they can be deceptively powerful when deployed as a swarm, often taking the place of much bigger satellites. CubeSats themselves are cheap to make, about $5,000 to $8,000. Launching them is the real expense (still tens of thousands of dollars). But that's today. If we waited a few more years, Made in Space or another company like it could solve this problem for pennies on the dollar.

"Turns out," says Dunn, "the ISS [is] a perfect platform for launching things into low-Earth orbit. Already our printers can print the cube portion of a CubeSat, and we've also printed the electronics in our lab. It's hard to say for sure, but around 2025 we should be able to print electronics aboard the ISS. This means we'll be able to email hardware into space for free, rather than paying to have it launched there."

Of course, the big dream is to be able to create 3-D printers capable of printing entire space stations in space and, even better, to do it with materials mined from space. Once this becomes possible, the creation of off-world habitats (i.e., space colonies) becomes a viable reality. "Imagine being able to colonize a distant planet by bringing nothing but a 3-D printer and some mining equipment," says Chen. "It might sound like science fiction, but the first steps toward making it a reality are happening in our lab right now, and aboard the ISS."

"It's such a cool capability to have a 3-D printer in space," says S. Pete Worden, director of NASA's Ames Research Center, where Made in Space is located. "Obviously, you save mass and volume by printing tools and parts on demand, but I'm also really excited for the future of printing spacecraft in space. Soon, you won't have to design spacecraft to go through an intense few minutes of launch forces [because] you can design and print something more elegant for microgravity, in microgravity."

In other words, if all goes as planned, Made in Space might end up as the first-mover advantage in the multitrillion-dollar industry that could eventually be off-world living.

Steven Kotler is the best-selling author of Abundance and The Rise of Superman. His latest book, BOLD: How to Go Big, Make Bank, and Better the World, explores the link between the world's biggest problems and the world's biggest businesses.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.