When masked gunmen smashed their way into the offices of the Crimean Center for Investigative Journalism, the staff knew what was coming. For years, the center had been a lone crusading voice exposing corruption in Ukrainian government circles while defying threats of violence and attempts to close it down.

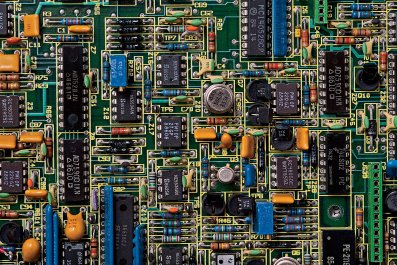

Now it was payback time as the thugs trashed the premises, seizing computers, hard drives and confidential files. Their objective was clear: erase the center's "institutional memory" by taking its website, containing some 16,000 pages of dedicated investigative reporting, off the Internet for good.

With no time to lose, a hasty distress call was made to an office 6,500 miles away in San Francisco, a converted church that is home to the Internet Archive and its vast digital library. Within minutes, archive technicians began to "harvest" the website, methodically copying and storing the contents to add to its Ukraine Conflict collection.

By the time the center's site was finally shut down in March—albeit put back up soon after—everything it contained, including more than 5,000 videos, had been preserved and made accessible online. It was another coup for Internet Archive's founder, Brewster Kahle, who is also behind the hugely popular Wayback Machine, an enormous online museum that enables users to see what a website looked like at any time since 1996, the year Kahle set up his first commercial web crawl company. Kahle's operation now costs around $10 million a year, covered by revenue generated by web crawling services, grants, donations and a foundation established by Kahle and his wife.

Kahle is a history-maker: on the front line with other archivists around the world deciding what digital artifacts should be gleaned from the universe of information and stored for future generations to access. "Websites disappear into the digital equivalent of a black hole all the time.… Their average online life in the U.K. is just 75 days," says Helen Hockx-Yu, who leads the British Library's web archiving operation, rated by experts in the field as among the best in the business. "A lot of material, including sites dealing with the 7/7 bombings in London in 2005 and the 2008 financial crisis, has been lost because we weren't able to capture it in time."

It is only 25 years since Sir Tim Berners-Lee invented the web, and there are more than 600 million websites, with some 4,000 domain names registered every hour. So great is the volume of data being generated that a new number may soon be required to quantify what is being stored, replacing the current largest number, known as the "yottabyte," a byte multiple that contains 24 zeros after the first digit.

Yet whether as a result of hostile governments closing down domains or organizations no longer able to pay Internet service providers to maintain them, the drain of valuable material is relentless.

I met Hockx-Yu in her office at the British Library, London. Brisk, articulate and smiling indulgently when I produce my Stone Age technology in the form of a notebook and tape recorder, Hockx-Yu is now on the front line of the most ambitious expansion of the British Library's archiving capability in more than 300 years. At the stroke of midnight on April 5, 2013, legislation known as the Legal Deposit regulations came into force, charging the library with capturing the contents of the entire U.K. web domain—every site carrying the .uk suffix—preserving the material and making it publicly accessible.

"The most exciting thing about web archiving is that it allows us to capture living history as it's being made and to store essentially ephemeral material for posterity," she says.

Together with the National Libraries of Scotland and Wales, the Bodleian Library in Oxford, the Cambridge University Library and Trinity College's library in Dublin, the British Library is now empowered to receive a copy of every U.K. electronic publication. This is a logical enough extension in the digital age of its ancient right to receive and store all books, newspapers, magazines and other printed matter, but it is still a challenging task. Eventually, Hockx-Yu's team could also be responsible for collecting copies of every tweet or Facebook page in the U.K. web domain.

The first full-scale Internet "crawl" (digital shorthand for browse and copy) was launched from the library's West Yorkshire computer center shortly after the law took effect. Covering 4.8 million U.K. sites, it took three months to complete, with another two months required to process the 1 billion captured web pages. The expectation is that the library will collect in a single year about the same amount of material as its newspaper and periodicals archive has amassed over the course of three centuries (a costly program to digitize some 40 million of its 750 million printed pages is now underway).

Chief Executive Roly Keating points out that when the initial crawl began, the project represented a reassertion of what it means to be a library in the 21st century. "Ten years ago, there was a very real danger of a black hole opening up and swallowing our digital heritage," Keating says. "Millions of web pages, e-publications and other nonprint items were falling through the cracks of a system devised primarily to capture ink and paper."

Professor Niels Brügger, the head of the Center for Internet Studies at Denmark's Aarhus University, supports the British Library's archiving project. "More and more of our societal, cultural and political activities now take place either on the web or are closely related to it," he says. "Since the mid-1990s, you simply couldn't be a university, a company or a political party without having a website. If we want to document our present or study our past on the web, get it into an archive before it disappears.

"Whenever I'm asked why web archiving matters," he continues, "I think of the Bob Dylan line from The Times They Are A-Changin'—'The present now will later be past.' Material is disappearing before our eyes at an unprecedented rate, and with it goes precious source material for the future historian who will be trying to shed light on the present. Capturing the past for posterity through web archiving matters just as much as preserving other aspects of our cultural heritage, whether it's kitchen utensils, buildings, warships or collections of newspapers. Studies suggest that 40 percent of what's on it at any given moment is deleted a year later, while another 40 percent has been altered, leaving just 20 percent of the original content."

Almost every major national library in Europe now undertakes web archiving, though the scale and cost of such operations vary widely according to their individual remit. The British Library's project cost some $5 million to set up, the money coming entirely from its grant from the Department of Culture, Media and Sport.

Swift action by the Crimean journalists and Internet Archive saved their precious source material, but there was no such option for staff at a human rights organization in El Salvador. Last November, heavily armed men stormed their office, intent on destroying the only reliable records of more than a thousand children who went missing during the civil war that ravaged the tiny Central American nation in the early 1980s. After overcoming guards, the intruders removed the group's computers and methodically torched its files: An eyewitness said that they were directed by a man receiving instructions over a two-way radio.

As much as 80 percent of the organization's research material was destroyed during the raid, widely attributed to factions opposed to the investigation of horrific crimes committed during the war. There is an urgent lesson to be learned from that incident, said a veteran U.S. activist: "The human rights community needs to think about systematic strategies to protect these archives." Meaning: The technology is there; ignore it at our own risk.

A certain wariness is apparent when Hockx-Yu explains the British Library's approach to the challenge of harvesting social media sites, especially the increasingly sensitive issue of privacy. The U.K. civil liberties advocacy group Big Brother Watch has argued that plans to harvest the mountains of material posted on Facebook and other platforms represent a step too far. Its former director, Nick Pickles, warned that many people using such sites would be unaware anything they upload to the web could be preserved indefinitely. "The danger of unintended consequences is magnified by how wide the library has cast their net," he told the Financial Times.

So what would happen if somebody used Facebook to post a vitriolic diatribe in the wake of a bitter divorce? "We're very conscious of the privacy issues that might arise in the process of web archiving," Hockx-Yu insisted. "The law incorporates a 'take-down' clause, activated when individuals are able to establish that something in a site has caused them damage or distress."

The library is already committed to appointing an independent arbitrator to deal with such cases, she adds, "but I do think people also need to become more aware of the possible consequences of putting something out on the web."