It was a team of ringers, pulled from all corners of the country for a Memorial Day weekend tournament in Southern California. The centerfielder flew in from Texas. The first baseman, from North Carolina. The shortstop and cleanup hitter, from Florida.

Was this a baseball team or the crew for a bank heist? They met for the first time on the eve of the tournament, ran through one practice and then laid waste to the competition. In the championship game of this boys 10-and-under event, sponsored by United States Specialty Sports Association (USSSA) Baseball Program and held in Chino Hills, California, they led 18–0 after three innings. At that point the mercy rule was invoked, the game called. It all might have seemed the latest hideous breach between youth sports and sportsmanship if not for one detail: The conquering team was composed entirely of little girls. "We just couldn't stop getting on base," said the team's founder and manager, Justine Siegal. "And our pitching was so good."

Feature Stories is a part of a partnership between Newsweek and 92Y, New York's world-class cultural and community center dedicated to spreading new ideas and inspiring conversations about today's biggest issues. More 92Y American Conversation videos can be found here.

Siegal twice left her third-base coaching box during the seven-game tournament to dispense badly needed hugs to her charges, once for a player who was bawling after repeatedly striking out (there is crying in baseball). But Siegal, the founder of Baseball for All, a nonprofit organization dedicated to providing opportunities in baseball for girls, believes her team won more than a tournament last month. "This moment was a tipping point in the history of girls' baseball," says Siegal, a distaff diamond maverick who has thrown batting practice to several Major League teams. "For long-term growth, we need girls' youth baseball leagues."

Boys play basketball and girls play basketball (and both can earn college scholarships doing so). Boys play soccer and girls play soccer (ibid). Boys play baseball and girls play…softball? Why is that?

"At age 13, the choice is made," says ESPN softball analyst Jenny Dalton-Hill, a former All-American second baseman at the University of Arizona who is the NCAA career record holder for both RBIs and runs scored. "Am I going to move to the bigger field, am I going to go 60 to 90"—the distances, in feet, between bases—"or am I going to stay on the small field? Besides, conformity is easier. Girls don't want to be different."

Some do.

"I was 13 when a new baseball coach told me he didn't want me on his baseball team, and I decided then that I'd never quit playing," says Siegal. After being prohibited from trying out for the Hawken School baseball team in Gates Mills, Ohio, as a freshman, Siegal was eventually allowed to do so as a senior and made the squad. "If we tell girls they can't play baseball and shoo them over to the softball field, what else can't they do?" asks Siegal. "Where else aren't they allowed to be?"

Diamonds are a girl's best friend, the saying goes, unless they are baseball diamonds. Then the misses are misfits with mitts. "I wish I knew why everyone just assumes girls play softball," says Bessie Noll, a student at Stanford University. A Minnesotan who was raised mostly in Tokyo (both parents are teachers), Noll considers herself a baseball player. Her childhood team, Musashi-Fuchu, is the reigning Little League World Series champions. When Noll tried out for the freshman team at her high school, the American School in Chofu, Japan, she overheard one coach say to another, "Are we just going to pinch-hit for her every time?"

Noll made the team, though, and by her senior year was named both team captain and Most Valuable Player. This spring, as a freshman in Palo Alto, California, Noll started all 55 games as an outfielder for the Cardinal softball team. Not the baseball team. "For me, the choice was strategic and realistic: I might've played college baseball at a small school, but Stanford gets 12 full scholarships for softball to parcel out," says Noll. "You think about a future and the thing that you love, and there is no future Sailorsin baseball."

Punching Out Babe Ruth

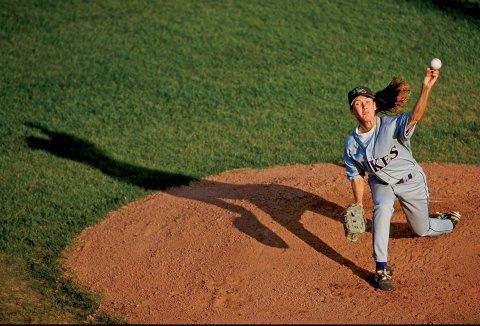

The town of Presque Isle is to Maine what Maine is to the rest of the United States: a remote spot in the northeast corner, colder and more sparsely populated. It is here, at the University of Maine-Presque Isle, that you will find the only female currently playing college baseball, pitching for a school that does not even have its own diamond. "We practiced inside our gym the whole season," says pitcher Ghazaleh ("Oz-a-LAY"—she answers to "Oz") Sailors. "But I don't care. I've never loved anything more than I love playing baseball."

Like its namesake town, Maine-Presque Isle exists on the outer fringes of college baseball. The Owls compete in Division III, although this past season that verb merited skepticism, as their record was 3–31, and two of those wins were at the expense of a junior college. Sailors, who was born and raised in Santa Barbara, California, attends college 3,300 miles away from home, about as far as two points in the Lower 48 could be from each other. Maine-Presque Isle's baseball program is even further from the College World Series.

And yet, in the lone win Maine-Presque Isle earned vs. a fellow four-year institution, Valley Forge Christian College in Phoenixville, Pennsylvania, Sailors was the winning pitcher. The 5-foot-4 junior hurled a complete game (shortened to five innings due to darkness) victory, allowing just one run on six hits, with eight strikeouts. "I'm all baseball, all the time," says Sailors, who also had the lowest ERA of any pitcher on the staff. "I believe in impossible dreams, and my dream is to be the first female college baseball coach."

Females have been infiltrating men's baseball, factually and fictitiously, for decades, and primarily as pitchers. Before Sailors, who made history a few years ago by facing a fellow female, Marti Sementelli, as starting pitchers in a California boys' high school game, there was Ila Borders. Before Borders, who was a starting pitcher for the Duluth-Superior Dukes, a men's professional minor league team, in the late 1990s, there was Amanda Wurlitzer. Before Wurlitzer (Tatum O'Neal), the fictional cusp-of-puberty staff ace of the Bears in the 1975 classicThe Bad News Bears, there was Jackie Mitchell, whose story seems even more improbable.

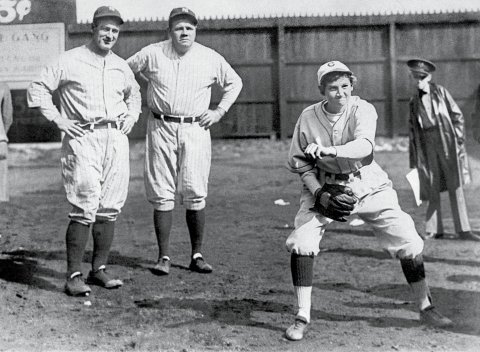

On April 2, 1931, the New York Yankees found themselves in Chattanooga, Tennessee, barnstorming their way up the Appalachians as they trekked from spring training in Florida back up to the Bronx. On that afternoon the Yankees, whose lineup included six future Hall of Famers, played the local men's professional team, the Chattanooga Lookouts, whose owner, Joe Engel, was known as "the Barnum of Baseball." The eccentric Engel once traded his shortstop for a turkey (then roasted it and served the bird to local sportswriters). And in 1931 he signed a 17-year-old southpaw named Virne Beatrice "Jackie" Mitchell.

On this day, the Lookouts' starter, Clyde Barfoot, surrendered hits to the first two Yankee batters he faced. Mitchell was immediately brought on in relief to pitch to…Babe Ruth. Mitchell struck out the greatest player the game has ever known on four pitches. The next batter? Lou Gehrig. The Iron Horse whiffed on three pitches. Mitchell walked the following batter, second baseman Tony Lazzeri, and was then removed from the game. While many fans believed it was a stunt, a conspiracy hatched between Engel, a former big leaguer, and the two Yankee icons, they printed the legend. The headline atop the sports section in the April 3, 1931, New York Times read, "Girl Pitcher Fans Ruth and Gehrig." An accompanying editorial noted that "the prospect grows gloomier for misogynists."

Mitchell could throw strikes, but Major League Baseball Commissioner Kenesaw Landis retained the authority to declare, "You're out!" Days later, Landis voided Mitchell's contract with the Lookouts on the presumption that baseball was too strenuous for the fairer sex.

Approximately four decades after Mitchell was banned from Major League Baseball, another Southern girl would face similar stonewalling on the diamond. Kim Mulkey was a 12-year-old girl in Hammond, Louisiana, in 1974 when she tried out for the Dixie Youth baseball league. "I didn't think much about my gender," says Mulkey, who is now the head women's basketball coach at Baylor University. "I just knew that when we played at school, I was always the first player picked."

Mulkey was also the first player selected that spring for the Dixie Youth league, and she was later chosen to play for the all-star team. However, when her squad advanced to a regional tournament, officials barred her not only from playing but also from even sitting in the dugout. "That was my introduction to disappointment in sports," says Mulkey, who has since gone on to win two collegiate national championships in basketball as a player and two more as a head coach. "As a female, if you're good enough and you enjoy it, go try out. Do it for the right reasons. If you do it for the wrong reasons, you just draw attention to yourself and make it harder for other women."

But what choice do women baseball players have other than to be mavericks? "I wish there was women's baseball alone," says Marti Sementelli, the girl who pitched against Sailors (and got the victory) back in high school. Sementelli pitched for two seasons at tiny Montreat College, an NAIA school in North Carolina, but after seeing only one inning of work her sophomore season, she transferred—not colleges, sports. This past spring the native of Sherman Oaks, California, batted third and hit .342 as a left fielder on Montreat's softball team. "I'm completely dropping softball for the summer," says Sementelli, who, like Sailors and Noll, will attend tryouts for the USA Baseball Women's national team this month (the Women's Baseball World Cup, a biennial event, will be staged in the first week of September in Japan). "I just want to play baseball in the World Cup."

Jon Gleason is the director of the USSSA baseball tournament that Justine Siegal's 10-and-under squad won over the Memorial Day weekend. While he praises the girls' achievement, he claims that there's a good reason girls do not play beyond puberty. "To be honest with you, they don't throw as well," says Gleason. "Go watch a girl throw a ball from third to first on a major league diamond if you want to see ugly baseball."

Dalton-Hill, the former All-American at Arizona, disagrees. "Zero, none at all," she says when asked if there are any physical barriers restricting women from playing baseball. She should know. In 1997 she was a member of the Colorado Silver Bullets, an all-female professional baseball team that barnstormed against men's teams. "One of the hardest things I've ever done, and not because of the baseball," she says, "but because socially, people didn't know what to think of us."

If the Silver Bullets, matched against high school or semipro men's teams, lost, that was expected. If they won, which they did about half the time that season, tempers flared. With two outs in the ninth inning of a game against the Americus (Georgia) Travelers, the boys state champions in the 18-and-under league, Dalton-Hill's teammate, Kim Braatz-Voisard, was plunked by pitcher Greg Dominy. As Braatz-Voisard started toward first base, she noticed Dominy laughing at her.

Braatz-Voisard rushed the mound. A bench-clearing melee ensued, boys against girls. "I mean, players were punching each other," says Dalton-Hill.

But why must baseball be a battle of the sexes? Why must every female baseball player be Billie Jean King challenging Bobby Riggs in a gimmick match, as opposed to being Billie Jean King facing Evonne Goolagong in the finals at Wimbledon? "Do I think girls like Marti and Oz are special to want to compete against boys?" asks Dalton-Hill. "Yes. But do they belong? No."

Softball, as the name implies, is soft. Noll, the Stanford outfielder, bristles good-naturedly at the "sexifying" of her adopted sport. "It's evolved to, 'What ribbons are we all going to wear in our hair?'" she moans. "You have no idea how much time is spent on this. It can drive you crazy. The 'girlie-fication' of the sport can demean it in some ways."

There's no good reason not to have girls' baseball on the collegiate level. As schools scramble to uphold the mandates of Title IX, which obligates them to provide equal athletic opportunities for female students, adding girls' baseball would not require additional facilities. It could become a fall sport, affording some softball players, such as Noll, an opportunity to play.

Of course, collegiate girls' baseball is not about to happen without high school girls' baseball. And that won't happen until a girl demonstrates that she can excel against the boys at that level. Unless…"There is one girl," says Dalton-Hill. "I saw her at a USA Baseball Women's camp, and there were Division I men's baseball coaches who were in love with her. She could get a D-I scholarship."

Meet Sarah Hudek. Sarah is a 5-foot-10 junior southpaw relief pitcher at George Ranch High School in Richmond, Texas. Her father, John Hudek, pitched four seasons for the Houston Astros (and her twin sister, Haven, is a varsity cheerleader). George Ranch plays in the Lone Star State's second largest class, in a state that has produced big league arms such as those belonging to Roger Clemens and Nolan Ryan. "She's pretty good," says her coach, Greg Kobza.

As a sophomore in 2013, Hudek allowed just one run in 24 innings and struck out 27 on the JV squad. This season, on a senior-laden varsity team that lost in the semifinals of the state playoffs, Hudek had a 1.20 ERA and struck out 11 batters in 10 innings of relief. In a recent playoff game, Kobza inserted Hudek into a tie game in the eighth inning with one out and the bases loaded. Not only did Hudek escape that jam, but she walked with the bases loaded in her lone at-bat of the season to drive in the go-ahead run, then retired the side in order in the ninth inning for the win. "She's got a two-seam fastball, a changeup and a curve," says Kobza, "but what people are most impressed with is her mound presence."

"I just want to open the door a little bit more for girls pursuing their dream of playing college baseball," Hudek told Houston CBS affiliate KHOU earlier this year. "It's possible. You just have to be mentally strong."

And you may need to occasionally charge the mound.