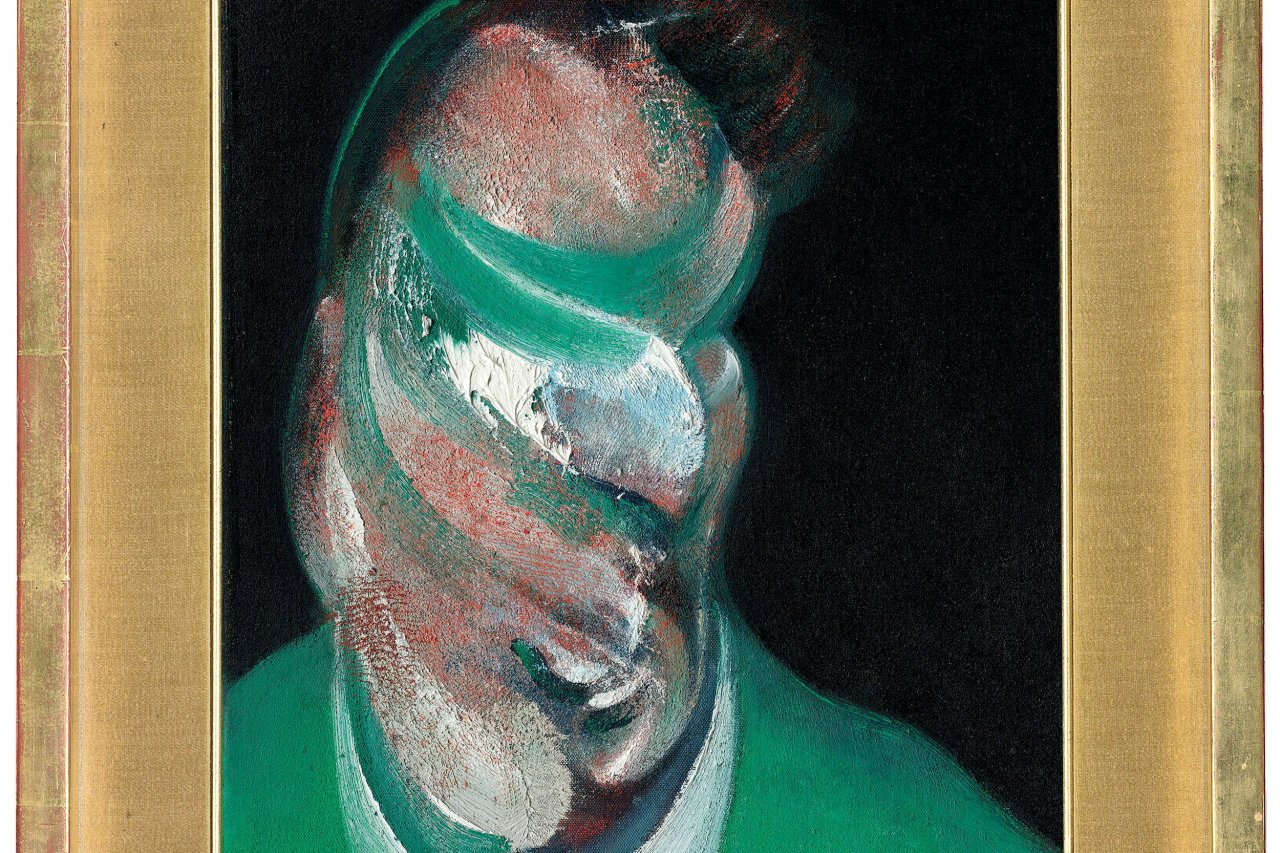

It is only a small painting but a hypnotic one that rewards endless examination. Francis Bacon's 1967 portrait of Lucian Freud is a lesson in the uses of oil paint—saturated, stippled and laid on in thick impasto. It is Bacon at the height of his abstract-realist powers. And it also reveals much about three of the great artists of late 20th century Britain.

The portrait was bought by the writer Roald Dahl soon after Bacon painted it and has been in the Dahl collection ever since. It is one of only two single portrait heads the artist did of their mutual friend; the other, painted in 1964, is in a private collection. And this one was not expected to go cheaply in a July 1 auction at Christie's. Last November, Bacon's full-length triptych picture (Three Studies of Lucian Freud, 1969) went for $142 million; pre-auction estimates for this smaller portrait (14 inches by 12 inches) were as high as $20 million.

The friendship between Freud and Bacon is well documented. Freud often painted Bacon, and, at one point in the mid-1950s, they practically lived in each other's pockets. As Freud's then-wife, the writer Lady Caroline Blackwood, put it, "I had dinner with [Bacon] nearly every night for more or less the whole of my marriage to Lucian [from 1953 to 1958]. We also had lunch."

Less well known is the relationship between Bacon and Dahl. The master of the disturbing, distorted portrait and the master of dark, comic literature were friends for more than 20 years. Dahl first came across Bacon's work in 1958, in an Arts Council show, and instantly recognized his talent, calling Bacon a "giant of his time" with a "blend of economy and profound emotion in [his] painting."

Dahl had been an avid buyer of modern art ever since World War II, when he served as a fighter pilot and intelligence officer. "Each time I sold a short story, I would buy a picture when there was a bit more money in the bank," Dahl once said. His tastes were wide-ranging—from Russian avant-garde artists (Kazimir Malevich, Alexandr Ermilov, Natalia Goncharova and Lyubov Popova) to Henri Matisse drawings and Winston Churchill landscapes. For many years, he took a Vincent van Gogh painting, The Potato Eaters, with him on his travels, hanging it overnight on the wall of various hotel rooms.

But it wasn't until the 1960s—and the financial success of his children's books James and the Giant Peach and Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, along with his screenplay for You Only Live Twice—that Dahl could afford to really indulge his passion for Bacon. From 1964 to 1968, Dahl bought four of his paintings.

The writer and the artist also became firm friends. They both revered van Gogh. They were both fond of lively evenings in Soho, and Dahl regularly had Bacon to dinner in his Buckinghamshire house in the 1970s and 1980s. Like Bacon, Dahl was an avid gambler. "They always got on," says Luke Kelly, Dahl's grandson and the managing director of the Dahl literary estate. "Roald thought Bacon was a genius.… They shared opinions, and they shared their liking for a drink. And I think all three men [Dahl, Bacon and Freud] shared something as outsiders; Bacon being Irish, Freud being German and [Dahl] being Norwegian. And they were all incredibly strong characters."

The actress Joanna Lumley (Absolutely Fabulous) was invited to a dinner for which Dahl's publisher had allowed him to devise his perfect guest list. She sat at Dahl's right hand and three seats away from Bacon. "Francis Bacon was on time, even though everyone said he'd be late and scruffy. He was marvelously, neatly dressed," she recalls. "Dahl was extraordinary: tall, very good-looking and frightening. He struck me as a kind of Viking, with slightly unfathomable qualities. I was conscious of not wanting to be an idiot. You're always anxious that you may say something wrong to your hero. He came into the room trailing clouds of glory."

When it came to buying Bacon pictures, Dahl chose well. Among his purchases were portraits of Bacon's great friend, the model Henrietta Moraes, and his tragic lover, George Dyer, who committed suicide in 1971. But it is the 1967 portrait of Freud that most captivated Dahl. And you can see why—in part because it reveals many of Bacon's varied techniques for applying oil paint. The background is a thick, saturated stippled black. To one side, Freud's chiseled profile, with his prominent cheekbones, is faithfully observed. On the other, figurativism collides with Bacon's characteristic semi-abstract semi-realism; tradition meets modernity. On the bottom left, the oil paint is roughly scumbled to give the impression of stubble. On his forehead, the paint is laid on with thick impasto to capture the gleam of the reflected light. And his right eye is caught with an equally thick splash of titanium white paint.

Dahl sold several of his Bacons—"He sold one to buy the local baker a new oven," says Kelly—but he always held on to the Freud portrait. "It is incredibly beautiful," says Kelly, "It's incredibly strong—with dark undercurrents. And my grandfather looked on it with reverence—he thought Bacon was a genius. It was kept right in the center of the living room, against a light pink wall."

Kelly spent a decade living with his grandfather at Gipsy House in Buckinghamshire. "The combination of the green and the black and the white is so powerful. Even the glass is amazingly clear—you feel like you can touch the painting."

For all Dahl's success in writing and in collecting, his life was in turmoil in the 1960s. In 1960, his 4-month-old son, Theo, suffered a severe brain injury after being struck by a New York taxi. Dahl was instrumental in developing the Wade-Dahl-Till device that helped relieve his son's hydrocephalus. He refused any commercial interest in the patent in order to extend the device's use as widely as possible.

In 1962, Dahl's daughter died of measles encephalitis at the age of 7. And, in 1965, his wife, the Oscar-winning actress Patricia Neal, had three burst cerebral aneurysms. Again, Dahl was central in helping with her recovery, retraining her to walk and talk. "He began an aggressive program in re-accessing those parts of the brain that had been cut off," says Kelly. "It would be simplistic to say that, with the Freud portrait, he was consciously going out to look at things to do with the head. But he was certainly interested in what was going on in the mind. He was interested in the fact that Lucian Freud was the grandson of Sigmund Freud. And, with all his art collecting, he thought it was important that you knew about the art, that you knew about the artist, that you knew about the sitter."

Dahl said as much in a 1981 interview: "You cannot begin to appreciate any work of art in the true sense until you have studied the personalities involved and the struggles they had."

Those struggles were particularly intense between Freud and Bacon. After their close friendship in the 1950s, the two men drifted apart. Despite the disintegration of that friendship—and the death of the three men—they leave a noble legacy of work behind them, not least the portrait that unites them. "My grandfather was an amazing, incredibly imaginative, different person," Kelly says. "He was always bubbling with ideas, schemes and fun. The picture will always remind me of him. It's a reminder that he wasn't just a writer, spy and fighter pilot, but also a wonderful art collector."