Xiao Jun, a 30-year-old who works for a business training firm in Beijing, had had enough. He had moved last year from his hometown of Guangzhou, in Guangdong province, southeastern China's capital city, and as is customary in China during the celebration of the lunar new year, the dutiful son had returned home in January to be with family and friends during the most important holiday on the Chinese calendar.

But he wasn't prepared for what greeted him. His relatives "were very keen" to set him up with girls, since Xiao was still unmarried, so the long holiday was full of meetings with single women his relatives knew. The only problem: Xiao is gay—and his parents knew it. Some months earlier, he had posted information about a gay event in Beijing on his WeChat account—China's most popular social media app—to which he had added his parents as contacts. Soon after, his mother called him and asked if he was gay. "I couldn't figure out a way to tell her, so I just told her the truth." She was silent for a long time, he says. "Then she hung up."

Once the awkward social encounters were over with the end of the holiday, Xiao confronted his parents. Why did they allow his relatives to set him on pointless blind dates? They responded that any man who doesn't get married "will be laughed at." He replied that "no girl will marry me, I'm gay." They then told him that they had "discovered on the Internet" that "homosexuality was curable."

What Xiao says next is what makes his story—and the bold turn it has taken—specifically (if not necessarily uniquely) Chinese: "I couldn't convince them of anything, so I had to pay respects to my elders." In the name of "filial piety," he says, he agreed to seek therapy to "cure" what his parents viewed as "his condition."

Pressure to conform to societal expectations, of course, is not unique to China's lesbian, gay, bisexual and transexual (LGBT) community. But there is one important difference. In China, a culturally conservative, Confucian society, the pressure family can bring to bear on children—particularly male children, who are expected to carry on a family's name by giving birth to a grandson—is "manifold greater than that in the West," says Ah Qiang, president of Parents and Friends of Lesbians and Gays—China (PFLAG), a national support group.

That pressure is only intensified by the country's controversial one-child policy, in place since 1979. Though amended since then, the policy still applies to roughly 40 percent of Chinese families and has led to huge distortions in the national population—including a lopsided male-to-female ratio of children born since the policy has been in place.

That pressure is why the vast majority of gay and bisexual men in China still hide their sexuality. According to the first China LGBT Community Survey, recently done by Community Marketing & Insights, a San Francisco–based research group, only 3 percent of gay men are "completely out." For many Chinese families, if the one son they have turns out to be gay, "they view it as a big problem," says Xiao. "That's simply reality."

It is that reality that led Xiao to board a plane on February 10 of this year to Chongqing, a huge, sprawling city in central China. He had searched the Internet and found a clinic "specializing" in "curing homosexuality." Such clinics are not necessarily plentiful in China's largest cities, nor are they common.

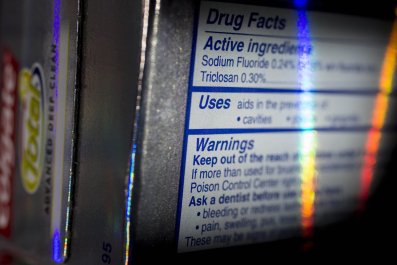

The first of many surprises was the price: A one-hour session cost the equivalent of $80. The full treatment, a counselor told him—which included "hypnosis, electrolysis therapy, and emotional diversion therapy,'' costs nearly $5,000. (Xiao cracks that he thought, Wow, we must all be doing really well financially.) OK, he said, let me start with the first treatment, and we'll see how it goes.

He was escorted to a room with a coach, who told him to take off his shoes, lie down "and relax." They would start with "electrolysis therapy." An electrode was attached to his left arm, and the counselor instructed him to "imagine I was having sex with my boyfriend. And then, when I was imagining it, to move my left finger."

Xiao did so, and instantly felt a sharp, painful shock in his left arm. Stunned, he asked the technician what was happening. The response: "They wanted me to have a feeling of horror whenever I had feelings for another man."

He quickly decided he was finished with the "treatment." "To get shocked like that won't turn me into a straight person," says Xiao, "it will turn me into a psycho." The next morning, he flew back to Beijing, met with a group of his friends and described the ordeal. They got "very worked up, very angry," says Xiao.

"It's totally a scam," one friend shouted at Xiao, he recalls. "We should stop this. A lot of parents will force their kids to go through with this kind of thing. If a doctor says so, the parents will believe it. We should stop other people from falling for this kind of thing."

The only question was how. That's when another friend in the group suggested he file a lawsuit. It would "bring attention and help put a stop to such clinics," the friend asserted. Before hiring a lawyer, Xiao and his friends did a lot of research. In particular, they looked into the background of a man named Cheng Kai, the senior counselor at the center in Chongqing. They found he has certification from the government to be a psychological "counselor," but he does not have authority to provide physical treatment of the sort meted out to Xiao.

In March, Xiao filed suit against Cheng and the center for violating their professional licenses, as well as Baidu—the Chinese search engine—for accepting advertising from the center, arguing that the company failed to do "due diligence."

A district court in Beijing heard the case in August, and as Xiao and his supporters hoped, it garnered widespread media coverage in China. A circus-like atmosphere surrounded the courthouse, with gay performance artists entertaining the assembled media. Inside the court, Cheng denied that he had given Xiao the shock treatment. But Xiao had surreptitiously recorded the entire session and was able to play the recording in court. When he emerged from the courtroom, Xiao says, "I was trembling."

A verdict is expected imminently. Lawyers following the case believe the allegation against Baidu will be dismissed. They are divided as to the merits of the case against the counseling center. In any event—the amount of damages Xiao seeks, $1,700 from each defendant—speaks to the symbolic nature of the case in China. And the president of PFLAG says the mere filing of the case, and the attendant subsequent publicity—there was voluminous and overwhelmingly supportive chatter on WeChat and other social media forums dominated by the young in China—means that Xiao has already won: "These are early days here [in the push for LGBT rights.] You can't compare what's happening here with what's happening in the United States or Europe. But this, this was a step forward."