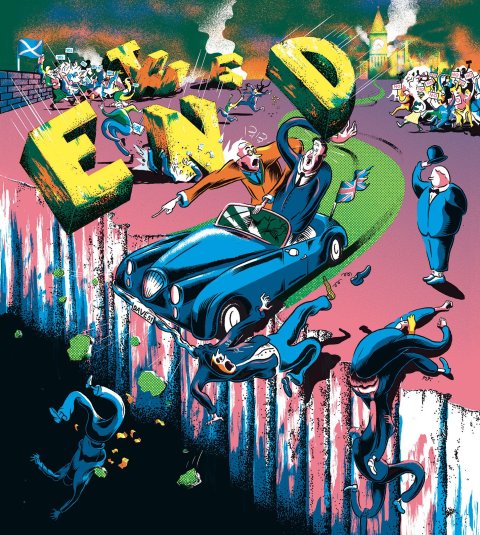

Scotland's referendum result has left Britain's political classes with a bad case of morning-after paranoia. A highly effective range of grassroots activist groups, covering a spectrum of leftist views from anti-capitalism to nuclear disarmament, has reinvented the whole idea of what an election campaign can be – it has helped the Nationalists and the pro-separation Green party serve up a cocktail of popular engagement and idealism to Westminster and Whitehall. But London's governing elite was already looking queasy.

Outliers on the right, the newly buoyant United Kingdom Independence Party, achieved a victory in the May local and European elections that humiliated the governing coalition parties, the Conservatives and Liberal Democrats, and also demonstrated they can take painful bites out of blue-collar support for the opposition Labour party. But that night's real winners were the stay-at-homes: turnout was only 34% compared to an EU-wide average of 43%.

Fracturing of traditional voting patterns makes next year's general election the most unpredictable for a generation, analysts admit, and the trends behind the pollsters' spreadsheets threaten the health of the mainstream parties. A new era of multi-party politics could be on its way. With it comes the prospect of near-permanent coalition governments – either formal agreements between two or more parties seeking a majority in the House of Commons, or the uneasy internal truces characteristic of parties that attempt to push a programme through while only enjoying a slim parliamentary majority.

Part of the change is generational. According to figures from Ipsos Mori, the proportion of British voters who always support the same party, already in decline, is set to plummet from around one third to just one in five within the next 10 years. Older voters are more likely to be faithful to one political tribe, and also much more likely to participate in elections: but – bluntly – these loyal voters are dying off. So by 2022 only 21% of the public are expected to say they back one party, compared to 50% in 1983. And only one in 10 of "generation Y" (those born after 1980) are expected to have these strong allegiances.

"These people will become quite rare," says Ben Page, chief executive of Ipsos Mori, "and there is no doubt that formal politics is under pressure."

In the good old days, power swung from red to blue and back again. The House of Commons benches of the much smaller third party, the Liberals, their allies and successor parties, filled and emptied without much impact on who governed: it was a "two-and-a-half party" system.

The midpoint of the 20th century, the 1951 general election, saw 96% of the British electorate backing either Labour or the Conservatives – and 82% turned up to vote. Today's leaders can only dream of that level of endorsement. Turnouts have been steadily falling, and as social class and family background cease to predictably determine political allegiance, voters have gradually become more promiscuous in their electoral habits – so much so that the winner-takes-all First Past The Post electoral system, designed to deliver majority governments, is failing to do so.

Since 2010, the Tories have had to rely on a coalition with the Liberal Democrats to form a government – standard operating procedure in most of Europe but in the UK a curiosity that pollsters say briefly intrigued the public, only to leave them even more disillusioned with their leaders once the inter-party compromises began.

The UK now has one of the lowest rates of party membership in Europe, and the steepest decline – less than 1% of the electorate belongs to one of the three main parties. It leaves the battles in the run up to the general election in May next year looking like a minority sport – what Page calls "the war of the weak".

The British Social Attitudes Survey shows that even those who still identify with a political party do so less fervently than in past decades. Disastrously for the country's political leaders, the same official survey shows that individual Britons are actually more politically active and interested than they were 50 years ago – they simply have no desire to do politics the traditional way. Membership of the smaller parties, the Greens, the Scottish Nationalists and now, dramatically, the anti-EU Ukip, has been rising since the millenium. And the internet has unleashed myriad e-petitions and campaigns, local, national and international, through which individuals can, in the atomised modern manner, engage momentarily by adding a signature or choose to become more involved.

Scotland's referendum has highlighted all these disruptions to "politics as usual", albeit refracted through an entirely unique campaign. But the high stakes and stark choice could be repeated as soon as 2017 in a referendum on Britain's membership of the EU, promised by David Cameron if he wins another term as prime minister.

That contest, if held, would again shake up a complacent political class – and, commentators on all sides agree, it could fatally split the Conservative party. After the Scottish experience, the pro-European side will dread it, since an "establishment consensus" between party leaders and business has now be proved to repel rather than attract votes. Distrusted by the public even when trading in verifiable facts, the mainstream parties have been powerless to sway opinion on the streets and in the pubs of Glasgow, Edinburgh and beyond. In fact, the presence of "English toffs" from the Downing Street in the pro-union campaign was seen as a major driver of votes towards "Yes".

As George Galloway, once a leftwing firebrand within the Labour party, now the only MP for his breakaway party Respect, wrote derisively but accurately: "Britain's political class may have achieved what Hitler failed to do. Destroyed Britain."

The hollowing out of the main political parties may not, of course, greatly concern the public. But politicians worry that the drama, and the constitutional danger of Scotland's decision, has awakened a new interest, half dismayed, half admiring, in how the Nationalists energised the electorate north of the border.

Deborah Mattinson, an adviser to the former Labour prime minister Gordon Brown, has been collecting ideas from panels of voters on how to revive democracy. They suggested the public might send in their own challenges to Prime Minister's Questions, the most notorious example of the "yah boo" style of Commons debating. Ed Miliband, the current Labour leader, proposes implementing the idea if he wins next year. Meanwhile the Tories have selected their candidate for the forthcoming Clacton byelection in a US-style open primary. One senior Tory backbencher is even calling for direct elections to the post of prime minister and for the government to be appointed from outside the legislature, along American lines.

"None of these ideas get to the crux of the problem," Mattinson complains, "which is people don't trust politicians." She and Ben Page both suggest that the electoral prize is what keeps MPs and think tanks poring hopelessly over the disengagement problem, rather than high-minded worries about Britain's democratic health: "Whoever gets this right, the win will be huge."

The Labour MP Gloria de Piero believes, like many, that the House of Commons needs, urgently, to become more representative of the population to prove its relevance and usefulness – her project to research public distaste for politics was called "Why do people hate me?" Unusual among MPs being both female, working class, and able to form an easy rapport with the public, de Piero is leading a campaign for Labour, to show that anyone, not just the political geeks, can take part in the national debate.

The Tories and Lib Dems are toying with all-women selection lists, in imitation of a mechanism that transformed Labour's gender balance in the 1990s.

Others propose a quota for ethnic minorities and the disabled. But ironically, the beneficiaries so far of all this impotent soul-searching, apart from the SNP's Alex Salmond, have been Ukip, who revel in being seen as Westminster outsiders, rejecting what they label a cosy liberal consensus on issues like diversity.

Patrick O'Flynn, for many years a newspaper reporter in the Commons, now a freshly-elected Ukip MEP, believes the 2015 general election will already be healthier and more fiercely contested and could even see a much higher turnout than in recent years: "the number of safe seats is likely to be much fewer than normal, there will be a wider choice of party – and there are big issues in play." His optimism, asserting that the volatility in voting intentions is healthy, may be partisan, but it rightly implies that the main parties are appalled to see their dominance challenged.

Page is not so sure MPs will welcome higher levels of participation if it introduces too much competition: "Yes, they are worried about turnout and legitimacy, but most would much rather win on 10% than lose on a 90% turnout." But the system and those protected by it may have to adapt: will Britain soon have an (albeit limited) market in parties and policies that mimic what modern consumers have become used to in the rest of their lives? "In the 1970s there were only three television channels, and now there are hundreds," O'Flynn argues. "The public is probably ready to embrace multi-party politics and has been for some time."

Some old hands in the commentariat are delivering doom-laden sermons, others are exhilarated: Chris Deerin of the Scottish Daily Mail, one of many celebrating the referendum experience, wrote of his delight in tasting "the pure, bubbling water of democracy" and wondered how to bottle it to nourish the post-plebiscite nation. But those who dismiss Britain's political turbulence as temporary sound less confident than six months ago.

What next, after the visceral shock of the referendum? Is the distress visible on the faces of party leaders Cameron, Clegg and Miliband during the last few days just an electoral hangover or the sign of something more lethal?

Across all the parties, old and new, there's an admission that British politics will not return to the age of commanding majorities for any one party – just as, says O'Flynn, modern TV shows can never hope to attract audiences of a size comparable to those in the late 20th century.

There is also a general recognition – reinforced by the result of Sweden's election – of broad European trends that are hard to defy: the financial crisis of 2008 and the recession which followed it have shaken faith in the powerful across the developed world. This, says economist Martin Wolf, in The Shifts and The Shocks, his book on the challenges of the post-crash world, "inevitably reduces trust in democratic legitimacy and creates outraged populism, on both the left and the right". Closer to home, the expenses scandal of 2009 has left a lingering suspicion about the motives of MPs.

But the Westminster show must go on, however bad the reviews – it cannot be taken off the air even if, as the Ipsos MORI projections demonstrate, the audience is dwindling. The mainstream parties, with only eight months to go until next May's electoral reckoning, will be meeting this month for their annual conferences during extraordinary times.

Expect yet more political introspection. For some in the ranks of the party faithful, the right response to this crisis will be trying to craft a version of the positivity that worked so well for the Yes campaign – but since they are part of the old order, this approach runs the risk of being dismissed, in the words of Sarah Palin to President Obama, as the "hopey changey thing" – just another brand of snakeoil.