Luther Blissett was transferred from Watford Football Club to AC Milan in 1983 for a fee of £1m. On his arrival in Italy he was shown around the vertiginous San Siro, a place that in those days resembled the average English football stadium as much as Harrods does a pawnbroker's. "Blimey, this looks a bit different," he said. "Where's the dog-track?"

English football was sordid, ragged and rugged: a game for the poor marked by violence and racism. Italian football was slick, subtle, clever, suave and fashionable. The English may have invented football but the Italians reinvented it and made it – of all things – sophisticated. Italian football was an expression of everything that England was not: rich, not poor; brilliant, not brutal; cosmopolitan, not parochial. "No matter how much money you have here, you can't seem to get Rice Krispies," Blissett said.

So in English press-boxes, the clever, cosmopolitan and brilliant Brian Glanville would slip effortlessly from English to Italian and back and use the word catenaccio in his copy for The Sunday Times. He wrote of an eternal sporting polarity: the uncouth yokel English footballer forever outsmarted by the city slickers of Italy.

Italy was where real football was. David Platt moved from the Birmingham club Aston Villa to Bari and subsequently played for Juventus and Sampdoria. "Someone asked me last week if I missed the Villa," he said, at the time. "I said no, I live in one."

When Italy staged the World Cup in 1990, it seemed that football had come to its spiritual home.

So, when Channel 4 broadcast Italian football in the UK between 1992 and 2002, audiences peaked at three million. James Richardson would introduce the programme from a café with a caffè and a copy of Gazetta dello Sport and it was compulsory viewing for football people. One look at a match – one pass – would tell you why. Kick the ball at a player in England and the ball would bounce back as if from a wall. Kick it to a player in Italy and it was as if it had struck a feather pillow: football at an altogether different level of skill.

Now everything has changed. Italy has become the sick man of European football, and here's a killer stat if ever there was one. In the summer transfer window, Hull City – a club whose genuinely great achievement is annually avoiding relegation from the Premier League – spent £39.5m. This is more than AC Milan, Inter Milan and Napoli – three great Italian clubs and serial championship winners – spent between them.

It's not true that Italy is the last place you'd look for great football these days. It's actually the fifth. European football's governing body now rates Italy's top division, Serie A, as the fifth league in Europe, behind Spain's La Liga, England's Premier League, Germany's Bundesliga and France's Ligue 1. As a result, Italy sends fewer teams into Europe's leading competition, the Champions League, and so they get less money. That's football: the poorer you are, the less money they give you, and vice versa.

Only three Italian teams were allowed in this year, as opposed to four from England, and of these, only Juventus and Roma qualified for the knock-out stages, where the real money is. Alessandro Nesta, who was a great player for AC Milan, told the BBC: "There's no money in Italy at the moment and the best players go to play in other leagues – Spain, England, Germany. Italy's going down."

There are two obvious questions arising from this: why did this happen, and, can it ever be put into reverse?

If you look at the attendance figures, you conclude that Italians have simply gone off the game. Average match attendances are 16,843, compared to 36,657 in the Premier League and 43,497 in the Bundesliga. If they can't be bothered to go, they obviously don't like football very much, do they?

But football is not a buy-and-sell commodity, any more than religion, with which it is often compared to. Football lays down cultural tap-roots. It's instructive to compare Italy's hard times with those of England in the mid-80s. English clubs were banned from participation in European competition after the Heysel Stadium disaster of 1985, when in the European Cup Final between Liverpool and Juventus in Brussels, 39 people were killed and 600 injured when a wall collapsed after Liverpool fans made a charge on opposition supporters.

It seemed then that, in England, football was inevitably associated with bad things. There was a nationwide craze for American gridiron football, and people were suggesting that it would replace the local variety: a product that was clean, expensive, classy, glamorous. But no. Football goes too deep, and what's more, it's not a product. The World Cup of 1990 reinspired England with football's joys: the founding of the Premier League two years later brought it whizzing back to the top of the nation's sporting agenda.

People are staying away from football matches in Italy because many of the stadiums are ancient and pretty horrible. These are mostly owned not by the clubs but by the local councils, with all the Italian public sector's problems of corruption and strikes. Clubs can't offer their punters very much at all, so they can't charge huge prices, and there are no facilities for money-spinning corporate stuff. Chelsea get six times as much match-day revenue as Roma.

So people watch on television. Until 2010, clubs negotiated their own deals with television companies. This didn't even work for the rich clubs who got the most, because it meant that the poor got poorer and so created too many mismatches. The current more democratic television deal is still below the English level.

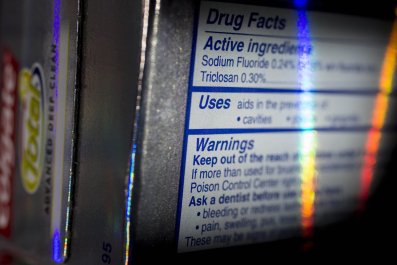

Besides, Italian football has got rather sordid, even if it can't rival England's dark days. There is still a good deal of violence associated with the game. Racism is a regular scandal: Mario Balotelli, a black Italian, said he was hounded out of his own country by racists. In 2006 a match-fixing scam was uncovered by Italian police: nicknamed Calciopoli, it involved Juventus, AC Milan, Lazio, Fioretina and Reggina.

Such things put normal people off. They also put off sponsors; it's not what they want their blue-chip name associated with. The Italian game has known plenty of troubles and must now seek to win back its own. The good news is that in football there is always a willingness to believe again. People and football are like that, as anyone who lived through the bad years in England knows.

Juventus moved into its own stadium in 2011 and has seen commercial revenues treble since then. It's the way to go. There are other suggested prescriptions for the sickness, most of them copied from the Premier League: title sponsor, better relationships with major international corporations, deeper exploitation of Asian pockets – all in all, a greater obsession with money rather than prestige or local rivalries or – perish the thought – football.

The first step in dealing with a drink problem is to accept that there is a drink problem. It's now clear to everyone in Italian football that there is a problem, that it's not something that they can laugh off and expect a renewal at the next turn of fortune's wheel. But change and regeneration are inevitable. The credit for the solution will eventually be claimed by various crash-hot business people, but they'll be fooling themselves.

The shoots of recovery will come all right – but they'll do so because the roots of Italian football are impossible to kill. And when it sprouts again it'll be like Giacomo and the beanstalk.