Ever since Matthew Drake was a boy, he dreamed of joining the Army. His mother, Lisa Schuster, had always been supportive. Then 9/11 happened. "I knew that would change everything for where our service members would be deployed and what they'd do," she says.

But the 9/11 attacks were just the catalyst Matthew needed to enlist. "He said, 'Mom, I grew up never being afraid or thinking something like this will happen…. Somebody has to be the good guys, and I want to be one of them.'"

On October 15, 2004, in Al-Qaim, on the Iraq-Syria border, a suicide car bomber drove into an armored vehicle filled with five American soldiers. Matthew, then 21, was the only survivor. He was rushed to an Army hospital in Baghdad, where he received emergency brain surgery. He was in a coma and on life support. Three days later, while being evacuated to Germany for further treatment, he suffered a stroke and nearly died. He had numerous broken bones and burns, damaged lungs and shrapnel throughout his body.

"It was questionable whether he'd wake up, walk and talk again," Lisa says. "But he has done all of those things."

After years of intensive therapy, Matthew, now 31, has recovered, to a degree. The attack left him with a traumatic brain injury, impaired decision making and problems with his short-term memory. His speech is slurred, and he walks with an unusual gait; strangers might think he's drunk. Six years ago, he moved into an apartment complex in Ann Arbor, Michigan, managed by a brain rehabilitation group with staff available 24/7.

The community is part of the Assisted Living Pilot Program for Veterans With Traumatic Brain Injury (AL-TBI), a federal program that ensures veterans with moderate to severe TBI receive care, therapy and enhanced rehabilitation. There are currently 96 veterans enrolled nationwide; 98 have been discharged from the pilot program since it began five years ago. Matthew has his own apartment, plus support from a staff that helps him with daily tasks, like going to the gym, attending Bible study, and making a grocery list and shopping at the store. The pilot was set to expire this fall, but President Barack Obama signed legislation extending it for three years.

"So many in Matthew's [medical] state are living with family members because they haven't been given this opportunity," says Lisa, who lives 40 minutes away in Sylvania, Ohio. Due to changes with Matthew's community, he may not be able to live there past March. That means Lisa will have to either move him to another community—to a new apartment with all new staff ("Big changes like this are extremely unsettling and difficult for somebody with a brain injury," she says)—or pay for Matthew to stay in his current home and receive the services he needs. But regardless of the future of AL-TBI, she hopes he will one day be able to live more independently, with less managed care. But finding—and affording—a community where he can do so is difficult.

"Neighborhoods aren't like they used to be in the old days, when I was young," she says. "There are safety factors. Right now, he is restricted from walking around the block alone because we don't know everyone there and they don't know him. He could be perceived by someone who doesn't know him as being…dangerous, because he might say 'hi' and wave to somebody and start talking to them, which someone might not feel is appropriate. And he can get lost."

Lisa wants Matthew to live as fully as he can—not cooped up in a room in her home, where she and her husband would take care of him. "But what's the future for someone like him?" she asks. "What's the next step for him when I'm not here?"

Too Old to Work, Too Young to Die

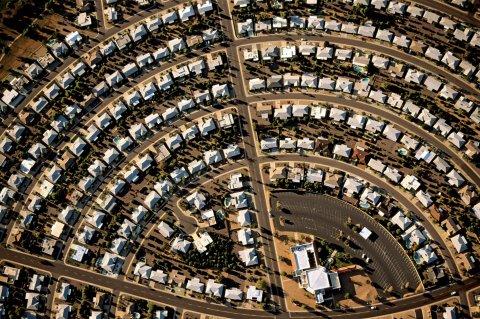

On the morning of January 1, 1960, the founders of Phoenix's Sun City, a new kind of retirement community, worried that few people would show up for opening day. There was much at stake: a $2 million investment; five styles of homes built on 20,000 acres, available exclusively to adults over 50. Then again, why wouldn't buyers bite? Sun City was advertised as the future of retirement in America, "an active new way of life" complete with a swimming pool and golf course; recreation and shopping centers; and a motel, restaurant and auditorium. Homes were affordable, ranging from $8,750 to $11,600. Sun City promised an age-segregated world where everybody was old—and so, nobody was old.

The founders hoped for 10,000 visitors that first weekend. By Sunday, 100,000 buyers had lined up, causing the largest traffic jam in state history. Those first two days, Sun City made $2.5 million. A year later, it boasted 2,500 residents. After 10 years, 15,000. By 1980, it was the seventh-largest city in Arizona.

Sun City wasn't the first age-segregated community in the U.S.—that honor went to Youngtown, also in Phoenix—but it helped launch what Marc Freedman, in his book, Prime Time: How Baby Boomers Will Revolutionize Retirement and Transform America, called "the reigning view of retirement as disengagement and leisure."

With the Social Security Act of 1935, the retirement age was set at 65. Never before had so many Americans been able to retire—and with a financial cushion, whether from pensions, their own professional success or Social Security. Americans also started living longer, and as retirement communities like Sun City popped up across the country, they offered an affordable solution for a generation of men and women who were, as labor union leader Walter Reuther put it, "too old to work, too young to die."

Sun City and its myriad avatars shaped our modern conception of our golden years, but their shiny allure dimmed over time, partly because they were chilly to children and astonishingly homogenous. Today, many baby boomers don't want to live out their days playing golf and bingo, watching television or pursuing other repurposed childhood pastimes. And in this economy, most can't afford to.

Beyond leisure, then, what do we expect of older Americans, especially a baby boomer generation 76 million strong? "Almost nothing," James Firman, president and CEO of the National Council on Aging, said during his keynote address this summer at the Age Boom Academy conference at Columbia University. "We have a gift of longevity," he said. "What are we doing with it?" So what, really, is the purpose of our "third act" or "encore years," that period from our 50s through our 70s?

"It's not retirement. It's not the golden years. It's not aging," says Freedman, who is also the founder and CEO of Encore.org. "We don't have a clear set of roles or expectations, nor a set of social institutions to prepare people for that time."

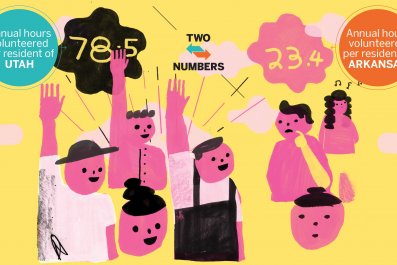

One solution may be multigenerational communities, where at-risk families (like foster families and wounded vets like Matthew) live side by side with adults in their 50s, 60s, 70s and beyond. Elders give their time and experience to neighbors, baby-sitting or teaching or cooking or meeting children at the bus stop; the experience helps them create meaningful relationships and develop a sense of purpose. In return, young people get the closeness and wisdom of surrogate grandparents. They grow up surrounded by a network of compassionate adults. The neighborhood is designed to make sure all the residents are actively and emotionally invested in each other.

"If kids are stuck in foster care, they remain a statistic—something tax dollars have to pay for," says Paul Halpern, director of one such community, called New Life Village, in Tampa, Florida. "It's an answer to a lot of issues from both ends of the age spectrum. It...could save us from ourselves, because my generation, the baby boomers, are getting old, and there's not going to be anyone to take care of us."

The problem is, very few people know about these communities. "The people who might want to do this—single adults who are 40 years old or small families who might want to adopt—don't know that we're here," says Halpern. "It's a culture-changing thing, and it takes a while to change a culture."

The Eureka Moment

In 1994, America's first multigenerational community, Hope Meadows, opened its doors on a converted military base in Rantoul, Illinois. The five-block, 22-acre neighborhood was designed as a community where adoptive parents would get the social and emotional support they need to raise their kids; foster children would have not just a home but a hometown, and older adults would have a community to give back to and, ideally, to grow old in.

Brenda Eheart, founder of Hope Meadows and executive director of Generations of Hope Development Corp. (GHDC), says the idea for Hope Meadows came out of the foster care crisis of the 1980s and 1990s, when children flooded the Illinois system in the wake of the crack epidemic. She was a professor of sociology at the University of Illinois, where she watched large groups of siblings being forced into foster care. All too often, they were not adopted together, and while many couples wanted to adopt for the right reasons, few had the support they needed to parent children from difficult family backgrounds and experiences.

That juxtaposition sparked Eheart's eureka moment: build communities where foster families and older adults live together, helping each other.

Today, Hope Meadows is home to 38 children and teenagers, 39 older adults and 12 parents.

In 2011, another community for foster families and elders, Bridge Meadows, opened in Portland, Oregon. Derenda Schubert, its executive director, recalls a day that spring when an older woman living down the street stopped by to introduce herself. She could barely afford her home, Schubert explains, and often struggled to pay for heat, medicine and food. Schubert recalls that when the woman learned what Bridge Meadows was and how much it cost to live there, she cried. She moved in the next month and, soon after, knitted a sweater for every child in the community. Today, she is one of 30 elders at Bridge Meadows, where she teaches a weekly arts and crafts class.

"Instead of feeling frightened [about] who would care for her," says Schubert, "she has kids who care about her. If she doesn't show up for art class, we all worry about her."

"We're interested in how to use this model to support vulnerable families: vets dealing with TBI, adults with developmental issues, young moms," says Mark Dunham of GHDC, which received a grant from the W.K. Kellogg Foundation in 2006 to take its community housing model nationwide. "It began with foster care, but it won't be limited, and the key factor is the presence of older Americans."

GHDC is working to replicate its multigenerational model for other at-risk populations. In Washington, D.C., a community for young mothers aging out of foster care is in the early planning stages. Three others are further along: Bastion, in New Orleans, for wounded war veterans; Hope Lights, in Puget Sound, Washington, for kinship and adoptive families, and Osprey Village, in Bluffton, South Carolina, for adults with developmental disabilities.

While Hope Village in Phoenix and New Life Village in Tampa didn't work directly with GHDC, they did adopt the organization's core principles: three generations, older adults volunteering their time for reduced housing costs, and a focus on vulnerable populations. The Treehouse Community, in Easthampton, Massachusetts, opened in June 2006. All three focus on foster children, adoptive families and older adults.

Bridge Meadows, which opened in 2011, has 27 apartments for elders and nine family homes spread across two acres. Rent ranges from $523 to $1,150 a month. The low cost, typical of these kinds of communities, will be an important selling point. By 2033, the number of older Americans will balloon from 46.6 million today to more than 77 million, according to the Social Security Administration. These men and women are living longer than ever before, and yet 34 percent of today's workforce has no retirement savings and 51 percent has no private pension coverage.

Paradise Lost…and Found?

Halpern, New Life Village's director (who is 63), was the first person to move in when it opened nearly two years ago. He grew up in a row-house neighborhood in Philadelphia. "There were 60 kids that lived on my block. You could walk into any of your neighbors' houses, without knocking; everybody's house was an extension of your house. Everyone looked out for each other," he says. "Now that's all paradise lost, because nobody trusts anyone else anymore. Part of it is an attitude of our American culture; there are really no communities anymore."

Halpern, a licensed psychologist, hopes New Life Village will change that dynamic for the few dozen families living there. The community has 31 townhouses on 12 acres; right now, 16 are occupied.

Halpern calls places like New Life "a tiny solution." In part, that's because choosing to move into a community with foster children transitioning into an adoptive family, or young mothers aging out of foster care, won't appeal to everyone. "It does take some courage for somebody to see themselves here—courage in a good way," says Halpern. "They're not endangering themselves, but they're doing things differently from the norm, and I don't think the norm is particularly attractive…. I think doing the traditional thing makes you older, faster."

Another challenge of the multigenerational community model is that these communities have space for only a limited number of residents. Many people don't even know about them, can't afford them or cannot uproot their lives to move to one. Bridge Meadows has a 12-person wait list for elder units, and that doesn't include the people who want to live there but don't qualify for affordable housing. There is no wait list for family units, but foster families typically don't have time to wait for housing.

"It's hard for me to imagine how, even if you scale them rapidly, you're going to reach more than one-tenth of 1 percent of the population," Firman says of multigenerational communities. He argues that a more scalable version would be the educational program that brought together students in Brazil looking to learn English with lonely older adults living in a Chicago retirement home. Each pair spoke via Skype.

The result: poignant conversations between young students and the elderly, across the Internet and two continents. "I want to thank you for this chance of experience, you know? You are incredible," one boy said to his video pen pal, an 88-year-old man. An older woman exclaimed to hers, "You are my new granddaughter!"

'The Future I Want for My Son'

Lisa Schuster had never heard of multigenerational communities until she met a young man based in New Orleans who just might have the answer to her concerns about Matthew's future.

Dylan Tete is behind Bastion, a new multigenerational community for wounded warriors, their families and older adults that is still in the planning stages. "Bastion is for surviving families, like a widow with small children. Or a guy like Matthew, with a brain injury. Or a guy like me, who had PTSD," says Tete. "And then, of course, the older people could be former military retirees or civilian retirees who just want to plug themselves into something and rediscover their purpose later in life."

Tete graduated from West Point in 2000. Three years later, he arrived in Iraq as part of Operation Iraqi Freedom. "I was second in command of an infantry company. Our mission was to destroy," he says. "We put bad guys away. We kicked down doors." Just over a year later, Tete came home, scooped up his wife and son, and moved to New Orleans in the spring of 2005. Three months later, Hurricane Katrina hit.

In its aftermath, Tete did everything he could to help. He oversaw the creation of three FEMA trailer parks. He took courses to become an emergency medical technician. He renovated devastated neighborhoods and a penthouse on St. Charles Avenue. He scrubbed blood off the sidewalk after a local shooting. Then he started working at City Hall, where he remained for three years. Each summer, he worked at a camp for children whose parents were killed in Iraq and Afghanistan. Eventually, he and his wife had another baby.

Through all of this, Tete suffered from depression. One day, he considered suicide. "I remember thinking, I'm going to kill myself, this is it. I had already been entertaining it, and so it must have been a good day, and not a bad day, because as soon as I said it, I immediately checked in at the VA."

After getting help, he decided to find a way to help other soldiers like himself. If all goes as planned, Tete says, construction on Bastion will begin next summer and the community will have its first residents in 2016. Tete developed a partnership with Mercy Hospital in New Orleans and established a leadership committee to help fund-raise. He meets with local politicians and families all the time.

"I have a lot of peers coming home from Iraq and Afghanistan asking the same question: 'What is the point?' I've asked myself that many, many times," says Tete. "To have support of an entire community is something that military people get, because we're used to that. You lean on me, I lean on you. You've got my back, I've got your back, and together we'll get through this. So it's actually a very natural concept."

Bastion has already garnered interest from Vietnam vets as well as baby boomers with no connection to the military. "The idea of a community reaching out to returning war fighters is something my generation did not experience very often," says Michael Dancisak, 61, director of the Tulane Center for Anatomical and Movement Sciences. Dancisak, a Vietnam-era veteran, likes the idea of living in a community like Bastion—one day. "Those who've been in war zones, there's something about it that stays with you your entire life…. There's a sense of comfort knowing there's somebody at hand who can help out anytime and understands why you're there."

Lisa dreams of the same experience for her son. "If Matthew were in a community where he knows his neighbors and they know him, he could walk around the block with a service dog. He won't be perceived wrong or deemed unusual or different," she says. "He'll be greeted with his head held high. What a difference! That's the future I want for my son."

Asked if she would want to live at Bastion, Lisa laughed. "I could see myself going to live with Matthew someday, because I need a place to live and he has a home and a great community that I could share with him.…" She pauses. "It chokes me up," she says, adding, "It wouldn't be because he needs to live with me. That's what I want for my son. The only way to get that kind of independence is in a community like this."