A survey, commissioned by Newsweek Europe and published by YouGov, contains some startling results that make clear what has been the major change in the British public's attitude toward the monarchy. But this is not a shift in terms of opinions about The Queen, Prince Charles or even Prince William – rather it is in terms of the public person of Catherine, Duchess of Cambridge, on whom, it seems, the future rests.

The British people remain as one in wishing their universally-admired Queen a long reign yet. But when the day comes and the throne passes to Charles, something else, something less immediately obvious will happen. On that day, the central matriarchal figure of the family will suddenly be Kate, née Middleton. The role will drop straight through the trapdoor of the generation above her and fall squarely upon her shoulders – for obvious historical reasons, Camilla cannot assume and would not wish to assume such a mantle. Instead, it will be Kate at the centre,surrounded by the throng of Windsor men – Charles, William, Harry, George, and another son perhaps. She will be daughter-in-law of the King, wife of the King thereafter, sister-in-law to his brother, mother to the King yet to come, grandmother to the monarch beyond – the friend and confidante to all these Kings and heirs of Britain. She is 32 now and the most intelligent among them. With each passing year, as Britain moves deeper into the 21st century, her position will further crystallise and declare itself. Kate will become the centripetal force around which the monarchy revolves. And in her public person, the 21st-century nation will be represented and seek to reflect its modernity and its ideas of womanhood.

PRINCESS OF PARADOX

So what is the public attitude towards the Duchess of Cambridge? What does she represent? What is changing? Do women look up to her? Should they? Can she speak to feminism? Do the British people wish her to step forward and inhabit her character, or is their perception that she will remain a blank page on which they write their own version of the future? What does the Duchess of Cambridge mean for the monarchy and therefore Britain itself?

This YouGov survey throws up some fascinating and seemingly contradictory results.

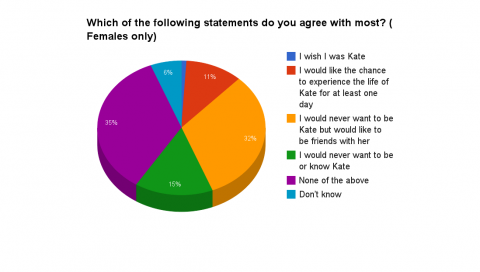

Astonishingly, only 1% of female respondents wish that they could be Kate. A staggering 89% of women have no interest in being Kate even for a single day. Meanwhile, among male respondents, only 6% wish they were married to Kate and – even more surprising, perhaps, – only 6% wish they were dating Kate. (Imagine the answers to these same questions in 1984.) When asked "Which of the following things, if any, are you interested in regarding Kate?", the following answers, among others, came back: her views on parenthood – 13%; her clothes – 6%; her make-up – 1%.

Respondents were selected from all over the country, including Wales and Scotland. They were representative of the whole pie-chart of voters – Conservative, Labour, Liberal Democrat and even Ukip. They were split roughly 50–50 male and female. And they were taken from every age group from 18 upwards. By chance, the survey was conducted on the day of the announcement of the Duchess's pregnancy. And yet when asked which of that day's news stories they were most interested in, the public rated the news of a second royal baby fourth – only 7% being "most interested". This figure rose among 18- to 24-year-olds, but only to 9%. Ahead came the Scottish referendum, then Isis and the Ebola outbreak. Refreshing.

More telling still was that when respondents were then asked which of the stories they believed were the "most important". On the very day of the announcement, only 2% of people cited the pregnancy. Hardly anyone. Pollsters expected it to be a little more than that – if only for the one day, given that the other news stories were ongoing.

Interestingly, the Duke and Duchess were very close in third and fourth place respectively as "favourite royal". Among 18–24-year-olds, they were placed the other way around and in London they are dead equal. (The Queen came second behind Prince Harry, the nation's favourite royal.) Conversely though, the public believed Kate's influence behind the scenes in her relationship with the future king to be substantial – 76% believe she has some influence over William and 50% of those describe that influence as 'strong'. Indeed, when asked how important the role is that she plays in the royal family, 64% said she was "important".

See the full results of the poll here.

And so, a paradoxical portrait starts to emerge. While almost nobody would actually like to be Kate, large numbers believe that she is intelligent (49%) and even larger numbers (65%) saw her as a potentially positive role model. In terms of power and influence, 64% believe that she had some control over "her life generally" rising to 74%, who believed she had "control over how she raises her son, Prince George".

On the one hand, therefore, we have the portrait of a woman to whom the British public no longer attach themselves emotionally; they are no longer psychologically invested in her life; they do not project their own identities onto her; she is not a repository for the nation's sense of itself, nor of its dramas. On the other hand, there is strong evidence that people believe her to be intelligent, strong, responsible and privately influential. This paradoxical perception is perhaps best captured by the fact that 46% of women think she has influence in what she says in public and 41% don't.

What is going on? The short answer might be that the more childish registers of the public-royal relationship are fading – gone the envy, the hysteria, the adulation, the schadenfreude. (Freud might here offer up some thoughts on infant attachment theory.) The British public seem more prepared to view their relationship with Kate, and therefore with the future of the monarchy, for what it is: a socio-political contract.

At the same time, and as a consequence, public perception of the real person – a human being inhabiting a near-impossibly claustrophobic public space – seems greatly to have developed and matured. Hers is a delicate role comes the message, a life of privileges certainly, but not necessarily of pleasures. (To put it another way: "See ya, wouldn't wanna be ya.") There are dozens of possible reasons for this: the rise of social media and the shrinking of tabloid influence for sure; but chief among them is the public understanding of Kate's own relatively approachable background. The era of exoticism is over. Out with the fantasy, in with the reality. Human life, at least in the First World, is now omni-connected. No new star rising can do so without a visible and accessible trail. And, though it happened serendipitously – a marriage made in love – it is not a coincidence that Kate is set to become a major female figurehead of this new firmament.

A NEW KIND OF ROYAL

So what, then, of the Duchess's role as a 21st-century woman? What is she now? What can she be?

Germaine Greer, the queen of British feminist thinking, shares the general view: "Kate is a great deal more intelligent than the rest of the royals. She has been put in charge of William. She has a bastard of a job," she says. But Greer feels sorry for the Duchess and identifies sinister undertones. "The girl is too thin. Meanwhile, she is vomiting her guts up and shouldn't have been made to go through all this again so soon. It's not so much that she has to be a womb, but she has to be a mother. I would hope after this one she says, 'That's it. No more'."

When I ask about specifically about feminism, Greer laughs. "Kate is not even allowed to decorate her own houses. Even the wives of the American presidents get to do that. The whole thing is a mad anachronism. The 'firm' tell us that the first born will now become the monarch regardless of sex. Well, big fucking deal! Kate is not allowed to have an interest in modern culture, even in art – to collect, to attend openings. She is made to appear absolutely anodyne. She cannot do or say anything spontaneous. She has learned what she has to do and say and how to do and say it in the approved way. Spontaneity will get her in trouble."

In commenting on her intelligence and her connection to the art world, Greer is partly referring to the fact that Kate achieved two As and a B at A-level (placing her exceptionally high against the national average) and the further fact that she went on to achieve a 2:1 degree in the History of Art from the University of St Andrews, which is where her relationship with William began. But Greer's sense of a real but stifled woman – muted, contained, controlled – is common.

The distinguished writer, Marina Warner CBE, who has honorary doctorates from 11 of the UK's leading universities, including St Andrews, Kate's own alma mater, has made a career of studying and writing about, among other things, the deeper myths of European culture.

"The most insidious and virulent aspect of [Kate's] position – the clothes horse side of things – means she cannot strike a blow for women except for the most ironic way," says Warner. "But it is significant that she has had a proper education and this gives her real status."

However, when I put to Warner the idea of an incipient matrilineage – that Kate must surely become uniquely centripetal to the royal family, a different line of thinking opens up. "Yes, the myth of obedient and compliant wife is not corroborated by the history of the 21st-century royal family. You can see something of this in the current British mania for the Tudors. The mythic idea of female service is not as historical as people previously thought. And, actually, Kate attests to some of the gains of feminism, which the older generation of women often consider are overlooked by the younger," Warner says. "The fact that she was able to marry for love, that this was not a dynastic arrangement. Whomsoever it was who arranges these things, withdrew their authority. And this is something that women have fought for throughout the ages: to marry whom they please."

More than this, Warner feels that Kate is now in a position to avoid or subvert the deep mythic contours of European culture: "Our myths are usually unkind to public women – they exhort sacrificial narratives. Marilyn Monroe, of course, Jackie Kennedy. . . all the way back. I think the sort of thing that happened to Diana, which began with a woman abandoned and betrayed and ended as so often in tragedy, will not happen again. Diana became wired into her own story in a very Greek way. But Kate's ordinariness and her intelligence militates against the mobilisation of that terrible machinery and propaganda. Instead, there is an element in her public persona – perhaps because the class barriers are down – that allows the personal and the political to connect on a continuum."

In other words, something is there under the surface if it is allowed to speak. Something the British public sense and respect but no longer envy. Something that cannot easily be willed into following the old patriarchal narratives. Something meaningful that might make Kate a role model worthy of the name.

Caroline Watson, director and co-founder of Progressive Women, an organisation that seeks to "enable, inspire, and support women to achieve their full potential", puts it this way: "We have seen change in terms of the royal family in recent years, and I think Kate represents a different era, but she hasn't spoken." Watson doesn't say it, but I have the sense that she rather wishes Kate would speak and looks forward to that day. Women need and would like her to do so. "All these magazines – Heat, Grazia, Closer and so on – scrutinising women's bodies, it's not exactly misogyny, because so much of it is written by women for women about women, but we have to get away from that culture."

What is interesting about Kate – and what is interesting about the new survey – is that people are precisely not interested in her for these reasons. Or much less so than has hitherto been imagined. So is there an opportunity for her to flourish in a more healthy and noble direction?

WAITING GAMES

Of course, Kate's story thus far has been the very antithesis of a feminist narrative; quite literally that old pernicious fairytale: wait for a prince, become a princess and then cede all authority to the man while assuming the subservient role of mother and wife.

This mythic structure runs deeper than deep in European culture – we see it everywhere, not just in children's books but on the dust jackets of otherwise intelligent novels written and published by otherwise intelligent women. Time and again, the arrival of the male defines the female's life, confers meaning, worth and direction. His departure the same, but in reverse; the removal of the male agency leaves the female empty and bereft – and she must now "find herself". The sadistic nickname, Waity Katie, that was given to her by the British press in the years leading up to her engagement, played darkly into these underlying narratives. But this doesn't have to be the end of Kate's story, rather it can be the beginning.

Elizabeth Frazer is head of the department of politics and international relations at the University of Oxford. "In life and in politics, we can overcome our beginnings," she says. "It is surely not fated that Kate must live the life that her predecessors have lived. One of the surprising things is that structures can be broken or challenged and this happens all the time. It's happening now with regard to Scotland. Of course, there are lots of mythic ideas and narratives in play surrounding Kate – 'Isn't it great that she isn't stroppy?', 'Isn't she clever in hooking herself such a husband?' – but these imposed ideological accounts of womanhood need not define her. My sense is that – within the constraints of the office – she could mature into a great occupant of the role. Hers is the script to write however it is received."

Were Shakespeare alive 100 years from now, (still Britain's greatest interrogator and chronicler of the monarchy), he would identify the present moment of crisis as a good time to set a history play. He might begin the first act with the coronation of Charles. And he might end with the coronation of William. But, like Viola in Twelfth Night, Kate would produce all the play's momentum. And, like Rosalind in As You Like It, she would dominate the action with her ability to subvert the limitations that society and the establishment seek to impose on her as a woman. Indeed, something of this is apparent in Mike Bartlett's speculative new play, King Charles III, that has just transferred into London's West End for an extended run after a series of sell-out performances. The denoument of the action involves an effort by the Kate character to secure a dual throne for herself and William.

The only joint reign in the history of the British monarchy has been that of William and Mary (1689–1694). The YouGov survey suggests that the public already consider William and Kate somewhat as a single entity with her influence being very strong. Theirs may well prove a co-regency in all but name. William for show; Kate for substance. And, again, this shared responsibility could and should afford Kate further opportunity to lead, to shine and to speak, if for no other reason than Britain needs strong women who inhabit themselves fully and are not corralled into narratives that they themselves did not chose.

As Greer says: "Women still have very little power. They still have to become men. They can't make real things happen for themselves in the workplace. Or it's still extremely difficult. If they get stroppy, they're removed. They can't get real redress when they're wronged. They can't get redress anywhere."

Of course, the British have delighted in the ambiguity of sovereign power. But this is a collusive dance of veils and self-deception. The truth is that there is a clear difference between being involved in the politics of a nation and being involved in the polity of a nation. A monarch can stay out of the former and yet make a great difference for the good in the latter.

Britain is living through a period of accelerated change. The survey evinces a new, more sanguine attitude to the monarchy. After all the scandals of state, and thanks to Scotland (and to Ukip, perhaps), the British public are coming out of their slumber and they're in the mood for reengagement with the deeper aspects of the social contract. They are already addressing profound questions as to the origin of society and the legitimacy of authority. The monarchy must not only meet this new emergent British idea of itself, it must partake in the process and become its emblem. The public believe the Duchess of Cambridge well placed to do this; and it would surely be a deeper destiny than merely marrying a prince.