At a time when the worldwide media image of Islam is dominated by nihilistic merchants of extreme violence, and just as the world wearily mobilises to meet this savage threat, something calmly encouraging happens in Toronto, Canada, to help redress the balance. Eighteen years in the planning, the $300m Aga Khan Museum and Ismaili Centre complex opened its doors to the public on September 18th: two highly significant buildings by master architects in a new 17-acre city park. It is a cultural complex that celebrates the other Islam: the artistic, intellectual and scientific achievements of Muslim societies from ancient times to the present.

The Aga Khan is the super-rich worldwide imam and prince of the Ismaili branch of Shia Muslims, who number some 15 million across 25 nations and regions. Swiss-born, French-based but a British (and now also Canadian) citizen, 77-year-old Prince Shah Karim Al Hussaini Aga Khan IV looks like the businessman he is, but runs a series of charitable foundations mostly devoted to helping the developing world. In contrast the Toronto project exists to promote Islamic art and culture to the western world. He enjoys a racehorses-and-superyacht lifestyle, but the Aga Khan is a very active Islamic moderate and progressive, promoting secular pluralism, the advancement of women and the elimination of global poverty.

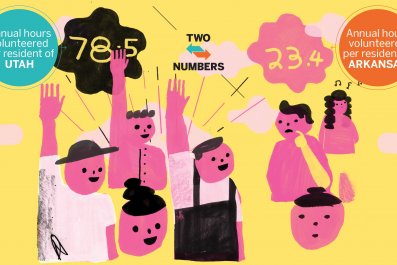

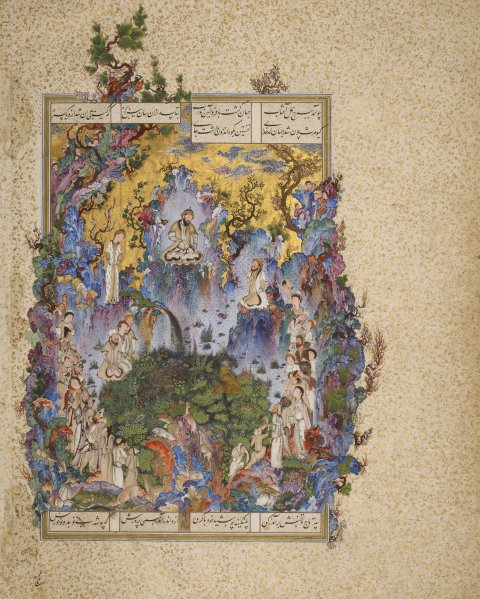

This enlightened Islamic cultural fightback is in an unlikely setting at first glance: a medium-to-high-rise business-park eastern suburb of Toronto, right by a busy multi-lane highway. The lush new landscape around the buildings, including 550 large mature trees transplanted for the purpose around a series of large, gently flowing rectangular pools, attempts to make a contemplative world of its own. Usually such public buildings are surrounded by acres of parking lots: here (this being Toronto where winters are harsh and snow-heavy) most cars are banished into a huge underground garage, so freeing up space for the park. And the Aga Khan has funded not only the museum but also donated its permanent collection of more than a thousand treasures including ceramics, illuminated manuscripts, 16th century Persian paintings, textiles and architectural fragments. There is exquisite work here: a planispheric astrolabe from Southern Spain in the 14th century, or the marvellously painted pages of the 16th century Persian Book of Kings. All that is on the ground level. Upstairs there will be an ongoing programme of temporary exhibitions – the place opens with two shows, one identifying the skilled artists of the royal courts of Iran and India from the 15th century, the other a look at today's contemporary art from Pakistan. It's also a performing arts centre with a packed programme, especially of music and dance.

The aim is, as Canadian prime minister Stephen Harper said at the opening ceremony, to demystify Islam "by stressing its social traditions of peace, of tolerance and of pluralism". The Aga Khan confined himself to the gracious platitudes expected of royalty on such occasions: it was his younger brother, Prince Amyn – instrumental in getting the project built – who spelled out why they were doing it. There was a "knowledge gap" between Muslim and non-Muslim societies, he said. "The result of that gap is a vacuum within which myths and stereotypes can so easily fester, fed by the amplification of extreme minority voices. Symbols become confused with emblems. Images of demagoguery or despotism, of intolerance and conflict, come to dominate in such an environment with global repercussions. I believe strongly that art and culture can have a profound impact in healing misunderstanding and in fostering trust even across great divides."

The two buildings are by famous octogenarian architects – Japan's 86-year-old Fumihiko Maki, responsible for the sharply-chiselled white granite museum, and India's 84-year-old Charles Correa, at the helm of the free-flowing Ismaili Centre including a virtuoso prayer hall beneath an all-glass pyramidal roof, rising 65 feet high. They sit side-by-side in the new park by Lebanon-based landscape architect Vladimir Djurovic. Exhibition design is by Adrien Gardère from Paris, so this is all as international as could be. It doesn't all quite hang together yet. Perhaps it's just too raw and new, perhaps the two buildings are just too different, maybe it's the curious Nowheresville setting, for this is nowhere near the city centre. When the landscape has filled out in a decade or so, it could be a very special oasis. For now, the emphasis is all on Maki's museum but the most telling architectural gesture is Correa's prayer hall: a genuinely uplifting light-filled space beneath its soaring double-skin opalescent glass roof, glowing at night like a beacon. Entirely modern, it is a powerful, mysterious object, duly aligned to Mecca. Maki recognised Correa's achievement, and in turn aligned his huge museum entrance towards it to frame the view: a nice gesture by one architect to another. As for Correa's own inspiration, he's pretty clear about that: it's the great American architect Frank Lloyd Wright who was a master at handling light. Religion? The Aga Khan is relaxed about that, pointing out at the launch that Correa had previously designed Hindu and Christian buildings. The only brief the Prince gave his architects was to design their buildings around the concept of light. "You have to have the freedom to speak in your contemporary voice," says Correa. "You devalue that if you just make a cartoon version of history. There's no need to do golden domes."

Why Toronto? The city was chosen not only for its famously multicultural, peaceful society (with a sizeable Ismaili population among it) but also for its proximity to the United States and a large population within a one-hour flight. But the self-funded nature of this place means that – unlike public art museums and theatres – it is not depended on grants or visitor numbers. Museum director and ancient history scholar Henry S Kim – previously responsible for the lauded £70m transformation of Oxford University's Ashmolean Museum in the UK – is forecasting a conservative 250,000 to 300,000 visitors a year. That's a quarter of the number that thronged his Ashmolean after it reopened, and Oxford is tiny compared to Toronto. Much will depend, everyone agrees, on the pulling power of a deliberately fast-changing exhibition and performance schedule. Plus, one hopes, curiosity, a desire to learn.

Progressive in spirit these buildings may be, but both make generous use of Islamic geometrical motifs – in floors, walls, screens, ceilings. The central courtyard of Maki's museum building has modern versions of the geometric paving and surrounding screens we associate with, say, the Alhambra. Though at the launch there was some spirited discussion among the scholars present about whether there was even such a thing as "Islamic art". Luis Monreal, general manager of the Geneva-based Aga Khan Trust for Culture, declared that the very idea was absurd given the overlapping societies and beliefs that gave rise to this art over many centuries – such as Mughal India, or Moorish Spain. Then there are the enormous differences between the art of the Arab Middle East, and that of the old Persian civilisations. The lesson of all this is the lesson of living together Monreal concluded. It's a compelling message in these times of atrocities perpetrated in the name of religion: that ideas and culture are what matter, and that these are all to do with people, not necessarily faith.